Talking Points looks back on 2020

Posted on 07 Jan 2021 Categories: Blog, Climate crisis, Coronavirus, Talking Points, The state we want

by Rethinking Poverty

2020 has been a year like no other in living memory, with two months pre-Covid and the rest of the year forming the first part of the post-Covid era. May also saw a worldwide wave of Black Lives Matter protests following the shocking killing of George Floyd by a white police officer in Minneapolis, and the end of the year finally saw Brexit ‘done’. How different will the themes covered by Talking Points look in this extraordinary year?

To answer this question, we begin by looking at Talking Points’ overviews of 2018 and 2019. Both led on deepening poverty and inequality and the emergence of ideas for a new economy. What was new in 2019 was the climate crisis – almost unbelievably, the word ‘climate’ didn’t feature once in Talking Points in 2018 – and the launch of the Green New Deal as a way to address both the climate crisis and the crisis of poverty and inequality.

In the end the themes covered in this year’s Talking Points don’t look so different from those in previous years. Poverty, inequality and the climate crisis all loomed large. But the context was different. While poverty and inequality have been exacerbated by the pandemic, the recovery presents unique opportunities to address them, and the climate crisis, and to #BuildBackBetter – and dire consequences if we fail to do so.

THE PRE-COVID MONTHS

Addressing the climate crisis

Forward to pre-Covid 2020 and the climate crisis loomed large, beginning with the 23 January announcement by the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists that the ‘Doomsday Clock’ has moved 20 seconds closer to midnight – the closest it has come to signalling a global meltdown and catastrophe.

Talking Points highlighted business and local initiatives to address the climate crisis. Pressure on business was coming from consumers, investors and employees. In January, a group of 11 pension and investment funds managing more than £130 billion filed a resolution calling on Barclays to stop lending to fossil fuel firms, while hundreds of Amazon workers defied corporate policy to publicly criticize the company for failing to meet its ‘moral responsibility’ in the climate crisis.

In the UK and continental Europe, cities were setting out their plans to reduce their carbon emissions. Nottingham announced its aim to be the UK’s first carbon-neutral city by 2028, while Bristol published a city-wide strategy to achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2030. In the Netherlands, Rotterdam was striving to become a circular economy by 2050 while Barcelona announced its plans to invest €563 million in measures to halve greenhouse gas emissions by 2030.

Citizens assemblies: a new form of democracy?

Meanwhile a new form of democracy was emerging in response to the climate crisis. The weekend of 25-26 January saw 110 people gathering in Birmingham for the start of the UK’s first UK climate assembly. The aim was to produce recommendations for how the government can reach its target of net-zero emissions by 2050 – which it did in September. How the government responds remains to be seen, but as a method of discussing difficult issues and reaching decisions about how to deal with them the citizens assembly seems to offer a promising model – a theme that was picked up by John Harris in September, in an article called If democracy looks doomed, Extinction Rebellion (XR) may have an answer.

Worsening poverty and inequality

Inequality remained a major blight in the UK. Among suggestions to address it were higher marginal tax rates for the better off (IMF’s managing director, Kristalina Georgieva) and ‘a massive power shift from London to local areas’ (public policy analyst Richard Vize).

February’s Talking Points reported ‘an avalanche of bad news on poverty’, including average living standards still £100 per year lower than in 2008, zero hour contracts hitting a record high, stalling life expectancy and as many as 14 million people in poverty in the UK. Among the suggestions for tackling this were a focus on wellbeing and taking the views of poor people into account in policy making.

ENTER COVID-19 AND A NEW WORLD

The onset of the coronavirus pandemic turned our world upside down. In March Talking Points reported on the massive and positive community response. The fight against Covid-19 is being waged street by street, wrote the Guardian’s Zoe Williams. ‘The horror films got it wrong,’ said George Monbiot. ‘Instead of turning us into flesh-eating zombies, the pandemic has turned millions of people into good neighbours.’ Coronavirus has exposed a desperate need for localism, said Simon Jenkins.

The state response was dramatic, with the British state unprecedentedly agreeing to pay the wages of those at risk of losing their jobs, increasing universal credit by £20 a week, and ordering schools to close and pubs to shut. What we are now witnessing is ‘the most dramatic extension of state power since the second world war’, said the Economist. While some saw the pandemic as ‘a chance to do capitalism differently’, the Economist warned that ‘a pandemic government is not fit for everyday life’.

EXACERBATING POVERTY AND INEQUALITY

The poor got poorer …

By April another dominant theme had begun to emerge: it was becoming increasingly clear that the virus affects poor people living in crowded conditions and unable to work from home more than wealthier people. This is even more true of ‘the accompanying economic shock’, said Torsten Bell of the Resolution Foundation. Just three weeks into the lockdown, the Food Foundation said that 1.5 million Britons reported not eating for a whole day because they had no money or access to food. By May the UK had seen 2 million claims for welfare support . Research from the Child Poverty Action Group (CPAG) and the Church of England, published in August, found that 80 per cent of poorer families surveyed felt they had become worse off financially since lockdown began.

In September, the Trussell Trust warned that by Christmas at least 670,000 extra people could become destitute – a level of poverty that leaves people unable to meet basic food, shelter or clothing needs – while the government’s former homelessness adviser, Dame Louise Casey, warned in October that the UK faces a ‘period of destitution’ in which families ‘can’t put shoes on’ children. In November the Legatum Institute reported that more than 15 million people in the UK – 23 per cent of the population – were now living in poverty.

As the pandemic progressed, it became clear that certain groups were going to be particularly badly affected, including:

BAME people

New analysis published in June showed that BAME and single-parent families were among those worst hit financially by Covid-19. In October, a new report by Baroness Doreen Lawrence showed that ‘Black, Asian and minority ethnic people had been overexposed, under protected, stigmatised and overlooked’ during the pandemic.

Children and young people

In September, a study showed that the gap in England between some pupils and their wealthier peers widened by 46 per cent in the school year that was severely disrupted by the coronavirus lockdown. Children and young people are at risk of becoming a ‘lost generation’, ‘scarred for life’, because of the UK government’s pandemic policies, members of Sage have warned. In October, the Food Foundation estimated that as many as 900,000 more children had sought free school meals, on top of the 1.4 million who were already claiming. Perhaps most shockingly, UNICEF announced that for the first time in its history it would help feed children in the UK.

The North

‘There’s an eight-year difference in life expectancy between the north and the south of the UK,’ wrote Lancet editor Richard Horton in October. ‘Is it a coincidence that the worst life expectancies in England track the upsurge in coronavirus? I don’t think so.’ A new report from think-tank IPPR North also found that Covid deepens south and north of England inequalities.

… and the rich get richer

Lower-income households are using savings and borrowing more during the coronavirus lockdown, while richer families are saving more as eating out and trips abroad are banned, according to the Resolution Foundation (June). In the US, analysis shows that in the span of three months, ‘the U.S. added 29 more billionaires while 45.5 million filed for unemployment’. In July, according to Swiss bank UBS, more than three-quarters of the world’s richest people were reporting an increase in their already vast family fortunes.

How to reverse these trends?

An income guarantee or universal basic income (UBI)?

NEF, OpenDemocracy and Compass all advocate some form of guaranteed minimum income, while on 21 April, 110 MPs and peers from seven parties called on the chancellor to introduce a Recovery Universal Basic Income. On the UBI side, the Liberal Democrats adopted it as party policy at their conference , while in October a cross-party group of more than 500 MPs, lords and local councillors called on the government to allow councils to run UBI trials.

More generous welfare benefits

New research has shown that nearly 700,000 more people have fallen into poverty during the pandemic, but there would have been twice this number without the extra £20-a-week uplift to universal credit. The government now faces a chorus of demands for the increase to be retained beyond April – from the Resolution Foundation , the Institute for Fiscal Studies and Gordon Brown, among others – and predicting dire consequences if it isn’t. Disappointingly, chancellor Rishi Sunak refused to commit himself to doing this in his November Spending Review. Other suggestions include ‘finally extending the same support to those on legacy benefits’ (Joseph Rowntree Foundation) , suspending the cap on universal credit (CPAG) and an urgent ‘family stimulus’ package (IPPR and the TUC).

A wealth tax

In December, the Wealth Tax Commission called for a one-off UK wealth tax to deal with the economic cost of Covid crisis – a call echoed by the Resolution Foundation, whose research has just revealed that official figures have missed £800bn of private assets. This means that the richest 1 per cent hold 23 per cent of UK wealth rather than 18 per cent as previously estimated. In July, more surprisingly, a group of 83 of the world’s wealthiest people published a letter urging governments to hike taxes on the super-rich to help fund the global recovery. ‘No,’ they write, ‘we are not the ones caring for the sick in intensive care wards … But we do have money, lots of it.’

#BUILDBACKBETTER

A mood for change

Even in the earliest days, this question was being posed. ‘At the end of the second world war,’ wrote Larry Elliott in mid-March, ‘the public asked themselves a simple question: if a more interventionist approach was right in wartime, why not try it in peacetime? When the Covid-19 crisis is over, as it eventually will be, they might well ask the same question.’

There seemed to be public appetite for change. In his article #BuildBackBetter, published on 7 April, Barry Knight concluded, following online group discussions with more than 80 people from universities and civil society organisations from all over the world: ‘we face a choice between trying to rebuild the systems we had or building new ones. In our discussions, we have not found anyone who would like to go back to the way the world was. People want to “build back better”.’

29 June saw the launch of #BuildBackBetter, a coalition of over 350 organisations from business, trade unions and civil society calling for a new settlement that protects vital public services, repairs inequalities, creates good jobs and tackles the climate emergency. This coalition includes the CBI, the TUC, the British Chambers of Commerce, Oxfam, the Trussell Trust, Greenpeace and many more.

The backdrop to the launch was a new YouGov poll showing that just 6 per cent of the public wanted a return to the pre-pandemic economy, with 31 per cent wanting to see big changes and a further 28 per cent wanting to see moderate changes. A July poll showed only 12 per cent wanting a return to the old ‘normal’ Britain after Covid-19. In October, the British Social Attitudes Survey found that public support for more generous welfare benefits was at its highest level since the late 1990s. A survey for the Mail on Sunday found 71 per cent of people supporting Marcus Rashford against the government over free school meals in school holidays. Johnson and the public mood are now poles apart, the Guardian commented.

Prescriptions for recovery

What follows is a very small selection of the prescriptions on offer:

- Reform the tax system (NEF and Common Wealth)

- Create jobs (Resolution Foundation)

- Cut the number of empty shops by putting communities in control of high streets (CLES)

- Create a national nature service to restore wildlife and habitats (coalition of environmental groups)

- Close the income gap (Richard Wilkinson)

- Adopt a four-day week (see below)

The state we want

There is widespread agreement that a highly centralised state is not what we want. ‘Rishinomics means centralisation like we’ve scarcely seen before,’ he wrote Simon Jenkins in July. ‘While across Europe millions of local officials were mobilised to care for, police, test and trace the Covid-19 pandemic, in Britain, some 2 million local government staff were simply ignored.’ He suggests giving elected mayors ‘short-term freedom to tax, borrow and spend’. In August, Polly Toynbee noted the government’s ‘belated climb-down over test and trace, finally admitting only local council public health expertise can do it’. John Harris also noted ministers’ reluctant acknowledgement that the anti-Covid effort will only work effectively if it is rooted in communities.

Throughout lockdown, the Better Way Network has been bringing together people from different sectors across the UK to understand how communities have been responding to COVID-19 and how we can use this experience to build a better future. The Inclusive Growth Network is an ambitious new initiative to incubate new ideas and policies that will help deliver change for local communities. The Carnegie UK Trust’s Pooling Together, not pulling apart report focuses on four community hubs that have been a critical part of the emergency response to coronavirus, while the Guardian’s John Harris pays tribute to the way local people have improvised during the pandemic.

What has also become clear is that we do need a strong central government, both to take the sort of national action we have been witnessing throughout the pandemic and to empower local governments. One big barrier to action by local councils is lack of funds. ‘Swingeing cuts and a lack of support from central government have hampered local authority attempts,’ says Bristol Green Party councillor Carla Denyer.

Rethinking the world of work

Working from home

A June survey of 1,500 people found that only 13 per cent of UK working parents want to go back to ‘the old normal’, with almost half (48 per cent) of those who worked in an office before lockdown saying they were considering asking for more remote working. Morgan Stanley has reported a mere 18 per cent of European office workers wanting to return to an office five days a week. But is the dream turning into a nightmare, asks John Naughton. ‘What’s basically happened is that the office has invaded the home. Or, to put it another way, we’re all sleeping in the office now.’ A recent large-scale study in the US found ‘significant and durable’ increases in the length of the average work day. In any case, says Kerstin Sailer, it is clearly impractical to suggest working from home as the new norm, ‘when many may lack the opportunity to set up a permanent and adequately equipped workstation.’ One suggestion for post-Covid working is individual pods designed to combine ‘the best parts of working from home with the amenities and collaboration of a traditional office’.

A four-day week

Flagged up by New Zealand prime minister Jacinda Ahern as early as May as a way to rebuild the country after Covid-19, a four-day working week is increasingly on the agenda. A four-day week in the public sector – a 32-hour week with no loss of pay is suggested – would create up to half a million new jobs, says think-tank Autonomy, and it would be affordable for most UK firms. Firms that have already introduced a four-day week are already reporting huge benefits.

Rethinking cities

Millions of former commuters are becoming aware of a different way of living, while there is rising interest in the idea that reclaiming time from commuting might benefit the economy. This will inevitably have a profound effect on city centres. To give one example, the end of August saw the announcement that Pret a Manger is planning to cut almost 2,900 UK jobs as sales plummet owing to the loss of passing trade.

So what next for city centres? Simon Jenkins’ sense is that for office work, the future lies with small towns and suburban villages, in ‘places commuters call home’. Along with other commentators, he insists this need not be bad news for cities. The decline in offices will leave more space for housing and for cultural and leisure activities, he says, especially in historic quarters. Architect Norman Foster sees a bright future for our cities, with ‘progressively less space needed for vehicles’. ‘An obsolete multistorey car park is the ideal urban farm,’ he suggests. We can replace the old high street with something better, thinks Owen Hatherley.

One enticing vision is the ‘15-minute city’, ‘a vision of urban living where everything you need – house, job, supermarket, school, park, health centre, post office – is a quarter of an hour away, by foot or bike. Paris, Barcelona, Bogotá and many other cities are exploring this. Neil McInroy of CLES sees the opportunity for community wealth building. UK cities should work for the people who live in them, not for distant shareholders, he argues.

WHAT ABOUT THE CLIMATE CRISIS?

‘In the future, we may look back at 2020 as the year we decided to keep driving off the climate cliff – or to take the last exit,’ wrote Justin Worland in July. On 22 April the Guardian reported on a new opinion poll showing that 66 per cent of Britons believe the climate is as serious a long-term crisis as Covid-19 and 58 per cent agree it should be prioritised in the economic recovery. Since April, competing camps are now locked in debate between those who want to get the economy moving again, no matter how, and those who see the crisis is a chance to accelerate the transition to a cleaner economy. Economist Jean Pisani-Ferry, a former aide to President Macron of France, describes this as the struggle that ‘will define the post-pandemic world’.

Significance of behaviour change in response to coronavirus

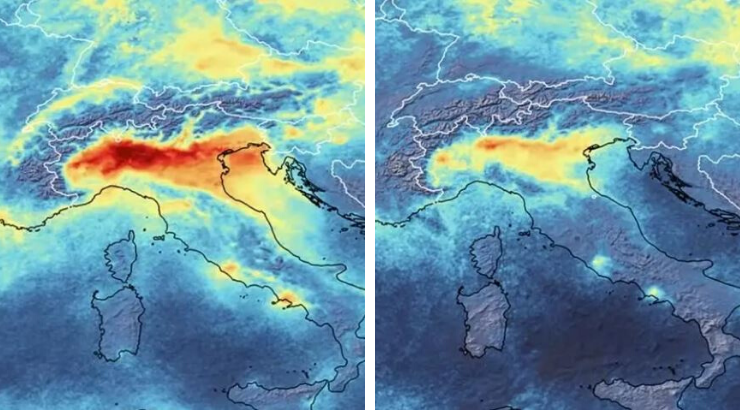

With industry and travel essentially paused, researchers immediately reported massive drops in the release of nitrogen dioxide, with parts of China showing pollution levels up to 30 per cent lower than normal. But Jason Hickel warned that changes were happening in an unplanned, chaotic way that was hurting people’s lives. ‘What we need is a planned approach to reducing unnecessary industrial activity that has no connection to human welfare and that disproportionately benefits already wealthy people.’

More significantly, ‘the shift in behaviour precipitated by the coronavirus pandemic is, perhaps, a sign that we can all make huge personal sacrifices when faced with a global, existential threat,’ writes Chris Stokel-Walker (Esquire). ‘The strong global response to Covid-19 demonstrated how quickly change could happen when humanity came together and acted on the advice of scientists,’ said Greta Thunberg.

Clamour for a green recovery

This has come from all sides. Leaders of international institutions urging people around the world to take a new path after the pandemic include UN secretary general António Guterres; IMF chief Kristalina Georgieva; executive vice president of the European Commission Frans Timmermans; Fatih Birol, executive director of the International Energy Agency; and the World Economic Forum. Within the UK, prominent advocates include the Committee on Climate Change, the government’s climate advisers; the Labour Party; the Trades Union Congress; environmentalist Jonathon Porritt; and CBI director-general Carolyn Fairbairn. More than 200 organisations representing at least 40 million health workers – about half of the global medical workforce – signed an open letter to the G20 leaders calling on them to ensure a green recovery that takes account of air pollution and climate breakdown.

Calls for a green recovery have also come from more unexpected quarters – from city veteran Lord Turner; The Economist and the IMF’s chief economist Gita Gopinath. Investors managing trillions of dollars in assets are warning the Brazilian government that escalating deforestation and the dismantling of environmental protections are ‘creating widespread uncertainty about the conditions for investing’, while Climate Action 100+ – an initiative supported by 518 institutional investor organisations across the globe – has written to 161 of the world’s biggest corporate polluters demanding that they back strategies to reach net-zero emissions. On 13 May, over 330 US businesses called on Democratic and Republican members of the US Congress to call for economic recovery that addresses climate change.

The British public, too, backs an ambitious transformation of the UK into a greener, fairer, more equal society as it emerges from the Covid-19 crisis. The consultation exercise found support for ambitious plans on equality, the future of work and the environment.

Are we actually heading for a green recovery?

There is no shortage of roadmaps. Rishi Sunak is said to be planning a ‘green industrial revolution’ to help to create jobs for people who are made redundant because of the pandemic. However, campaigning group Plan B has launched a legal challenge against the plans, arguing that they fail to take account of its obligations under the 2015 Paris agreement and the UK’s own net zero 2050 emissions target. Of the EU’s proposed €750 billion recovery fund, a quarter has been earmarked for climate action – though data from the Energy Policy Tracker shows that governments are spending vastly more in support of fossil fuels than on low-carbon energy.

Action at city and local level looks more promising. It seems that 54 cities are on track to meet targets under the Paris climate agreement. By autumn 2020, 75 per cent of local authorities in England had declared a climate emergency and hundreds of council initiatives are under way, though a lack of support from central government are hampering local authority efforts.

The end of growth?

There continues to be a general assumption that a greener economy means green growth, but there is a strong argument that infinite growth in a finite world is not possible – a case made by Positive Money and Local Futures, among others. George Monbiot begs people to stop talking about stimulus packages. ‘We have stimulated consumption too much over the past century, which is why we face environmental disaster. Let us call it a survival package, whose purpose is to provide incomes, distribute wealth and avoid catastrophe, without stoking perpetual economic growth.’

WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE?

At the end of 2020, the future looks bleak. How to save the United Kingdom is the heading of a November article by Gordon Brown. In his view, ‘the inequalities between our regions now wider and deeper than in any other major advanced economy worldwide.’ Writing in the Guardian a few days earlier, he describes the UK as ‘more divided than I have ever seen it before’. A late November Cabinet Office briefing warned that ‘Brexit, Covid, flu, flooding and unrest could lead to chaos’ and ‘an increased likelihood of “systemic economic crisis”’, raising the risks of ‘a breakdown in public order.

Amid 2020s gloom, there are reasons for hope. The Black Lives Matter movement has brought a new focus on racial injustice, while Joe Biden’s election marks a new beginning for the US – and hopefully for the world. There are also reasons to be hopeful about the climate in 2021, believes John Sauven of Greenpeace, while Justin Rowlatt, the BBC’s chief environment correspondent, also feels that 2021 could be a turning point for tackling climate change.

But the climate crisis can’t be – and shouldn’t be – tackled alone. What one could call the unity of injustice and inequality was underscored by the Black Lives Matter protests. As Peter Kalmus tweeted on 30 May, ‘Here’s why race justice and climate justice are one and the same: the oppressive extractive plutocracies that colonize and kill black bodies and colonize and kill our planet are one and the same.’ ‘The climate is an issue of social justice,’ said Bristol mayor Marvin Rees, the first elected black mayor in Europe, following the toppling of the statue of slave trader Edward Colston in Bristol in June. ‘People hit first and hardest by the destruction of the planet look like me and my father.’

Nowhere is the marrying of local social concerns with climate strategy better demonstrated than in the working class community of Lawrence Weston in north-west Bristol, one of the poorest neighbourhoods in the UK. The community is proposing to build a £5.4 million wind turbine. This would generate enough electricity to power 3,850 homes and generate an income for the community. Can we look to Lawrence Weston for a way forward in 2021?

Want to keep up-to-date with more articles like this? Sign up to our newsletter.

Posted on 07 Jan 2021 Categories: Blog, Climate crisis, Coronavirus, Talking Points, The state we want