Talking Points: August 2020

Posted on 02 Sep 2020 Categories: Blog, Coronavirus, New economic models, Talking Points, The state we want

by Rethinking Poverty

Lockdown has seen huge changes in the world of work – most notably the rise of home working. With the furlough scheme coming to its end and the government pushing people to return to work to save jobs in city centres, Talking Points looks at debates about the future of work and how changes in working patterns could affect the UK’s cities. We also look at growing and unwelcome tendencies to increased centralisation of the state and the danger that recovery will exacerbate already horrendous inequality in the UK.

Working from home – dream or nightmare?

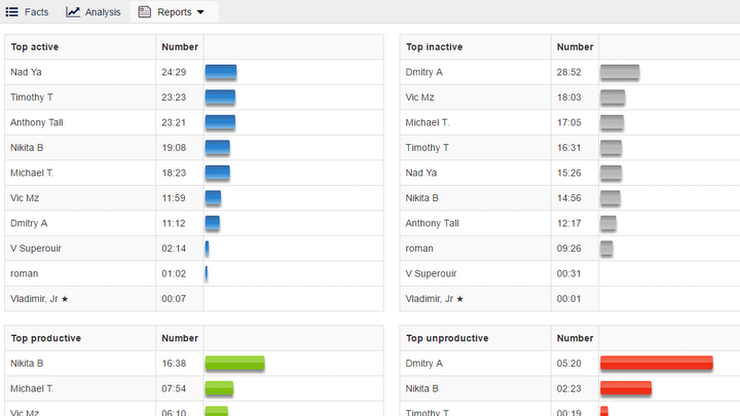

Working from home was the dream but is it turning into a nightmare, asks John Naughton. Work-life balance has definitely shifted during lockdown, he says – but in favour of the office. ‘We may be physically at home but many of us are working harder than we did when we were, physically, on corporate premises.’ Because people don’t need to physically move between one meeting and the next, Zoom meetings can be scheduled back to back. ‘What’s basically happened is that the office has invaded the home. Or, to put it another way, we’re all sleeping in the office now.’ A recent large-scale study by the National Bureau for Economic Research in the US, using data from more than 3 million workers, found ‘significant and durable’ increases in the length of the average workday along with short-term increases in email activity and an almost 13 per cent increase in the number of meetings per person. Wide deployment of surveillance tools for making sure that home workers stay chained to their laptops is also emerging.

Reimagining the world of work

So what comes next? It is clearly impractical to suggest working from home as the new norm, says Kerstin Sailer, ‘when many may lack the opportunity to set up a permanent and adequately equipped workstation’. In addition, research suggests that unplanned face-to-face interactions are important drivers of new ideas, an effect often known as the ‘strength of weak ties’. In fact, research has shown that weak-tie interactions have suffered disproportionately during the working-from-home period. ‘Covid will force us to reimagine the office,’ says Sailer. Earlier great ideas like Robert Propst’s ‘action office’ and Robert Luchetti’s ‘activity-based working’ led to the ‘workplace miseries’ of cubicles and hotdesking. ‘Let’s get it right this time.’

Entrepreneur Xu Weiping favours individual pods for post-Covid working. He is building 3-metre-square workspaces in east London with a chair, desk, fridge, microwave and fold-down bed. These enable colleagues and freelancers to work close to one another but mostly safely self-contained in their own pods. ‘The cubes are designed to combine the best parts of working from home with the amenities and collaboration of a traditional office,’ says Xu.

In a new report, Beyond the gig economy: Empowering the self-employed workforce, New Economics Foundation recommends ‘public and collective provision of advice, financial support, and guidance’ for self-employed people, recognising ‘the self-employed workforce as a significant and growing portion of our labour force’. Their first recommendation is provision of new self-employment centres across the country, alongside a Minimum Income Guarantee and parity of rights and social security, and a collective voice, for the growing self-employed workforce.

Rethinking cities

The increase in home working has had a profound effect on city centres. The end of August saw the announcement that Pret a Manger is planning to cut almost 2,900 UK jobs as sales plummet owing to the loss of passing trade. Hard on the heels of this announcement came a government announcement of a major media campaign to encourage workers to return to the office amid fears that town and city centres are becoming ghost areas.

So what next for city centres? ‘I can find no expert who expects them [workers returning] in anything like their previous numbers,’ writes the Guardian’s Simon Jenkins. Apparently, Morgan Stanley reports a mere 18 per cent of European office workers wanting to return to an office five days a week. ‘Commuting has come to be seen as an unnecessary health hazard,’ says Jenkins. ‘A worker visiting his or her office will be, like going shopping, an occasional discretionary activity. Yes, we will value the human contact with workplace friends, clients and associates, but not 9-to-5, five days a week. This treadmill was the ethos of Dickens’ factory work carried into the office. It is out of date … For office work, I sense the future lies with small towns and suburban villages … It lies in places commuters call home, where they can replace the ties of office with those of neighbourhood. The shift may be no more than 25 per cent, but in demography a trend is a revolution.’

Enter the ‘15-minute city’

Along with other commentators, Jenkins insists this need not be bad news for cities. The decline in offices will leave more space for housing and for cultural and leisure activities, he says, especially in historic quarters. One enticing vision is the ‘15-minute city’, ‘a vision of urban living where everything you need – house, job, supermarket, school, park, health centre, post office – is a quarter of an hour away, by foot or bike. Paris, Barcelona, Bogotá and many other cities are exploring this,’ says Izaskun Chinchilla. ‘It means making cities more pedestrian- and cyclist-friendly, and prioritising refurbishment over new construction, retrofitting buildings to include a greater mix of uses, such as retail, office space, education, small makers and housing.’ If we free up space in cities by reducing the number of cars, on the road, and with them the need for parking, we could plant trees, she says. ‘If we do that, natural species will follow, and biodiversity will increase.’

Leeds architect Irena Bauman sees Covid-19 to be an opportunity ‘to accelerate what has already been planned to address the climate emergency, such as installing a cycling network in the city centre that connects to surrounding neighbourhoods, and engaging the community in planting 1 million trees’. She sees this as ‘the first step towards remodelling our urban environments as “15 minute cities” … Our coronavirus retrofit should be the work of many hands, a sensitive process of rebuilding cities so they’re durable, equitable and sociable places to live and work, capable of dealing with the twin emergencies of the pandemic and climate crisis.’

The state we don’t want

Why does No 10 want to ‘devolve’ local councils just as they are needed most, asks Polly Toynbee. ‘What a time to launch a colossal centralising reorganisation of local government, but that’s what next month’s white paper will do, under the misleading rubric of “devolution”. The intent is to force unitary councils everywhere, sweeping away the district councils beneath them.’ Odd timing, she feels, ‘now Whitehall is forced into a belated climb-down over test and trace, finally admitting only local council public health expertise can do it.’ She notes ‘how the calibre of local government leaders and chief executives has soared in recent years’ and cites new evidence that the more local, the more trusted the politician.

John Harris also notes ministers’ reluctant acknowledgement that the anti-Covid effort will only work effectively if it is rooted in communities. ‘All outbreaks are essentially local, he says, ‘and like extreme weather events, they demand effective on-the-ground action and communication, and the kind of strong institutions that affirm people’s sense of place and solidarity … if the coronavirus has proved that doing things from the grassroots up is so crucial, why are so many aspects of our everyday lives being pushed in the opposite direction?’ A key plank of this is getting rid of section 106 agreements – which ‘often compel builders to include affordable housing in their developments, but also to make contributions to parks and public spaces, local education and community centres’. In concluding, Harris laments ‘our hyper-individualised future … no sense of place, no dependable local news, no spaces to gather – nowhere, indeed, to organise the kind of collective self-help that has recently been revealed as many communities’ last line of defence. In what looks set to be an age of disruption and disaster, we could not start from a worse place.’

Exacerbating inequality

There is growing evidence that the pandemic is exacerbating inequality in the UK – and the country starts from a very low bar in this respect. Recent research shows that BAME over-50s are more likely to be among the poorest 20 per cent in England than their white peers. They are more likely to retire later and have a lower weekly income (living on an average of £100 less per week), and are far less likely to own their own home.

Children, too, are faring badly. Children in the UK have the lowest happiness levels across Europe, with ‘a particularly British fear of failure’, the rise in UK child poverty and school pressures all cited as reasons. Only 64 per cent of UK children experience high life satisfaction, while children in Romania have the highest levels (85 per cent). Meanwhile, the gap between poor pupils and their wealthier classmates in England had stopped narrowing and gone into reverse for the first time in 12 years, even before the coronavirus pandemic hit.

But this already dire situation is getting worse. Researchers from the Child Poverty Action Group and the Church of England found that 80 per cent of poorer families surveyed felt they had become worse off financially since lockdown began. New research from the Social Metrics Commission has found that people already trapped in poverty are the hardest hit by the economic impact of Covid-19, including disabled people and those of Black and Asian ethnicities.

Meanwhile analysis by the Labour Party shows that England’s north-south divide could be made worse by coronavirus’s impact on the economy, with the most vulnerable sectors such as retail and manufacturing dominating the jobs market in certain regions. And Rebecca Johnson, presenting highlights of Joseph Rowntree Foundation’s discussion series on ‘shaping a recovery that reduces poverty’, refers to the reminder from Andrew Carter (Centre for Cities) that any decline in the UK’s cities would hit the poorest communities hardest, as they rely on the dense pool of urban jobs that home working threatens.

Close the income gap

The recipe for how to #BuildBackBetter after coronavirus is very simple, according to Richard Wilkinson: close the income gap. ‘Almost all the problems that we know are related to social status within our society get worse when status differences are increased. If we want a less dysfunctional society and a healthier population, building back better means addressing the scourge of income inequality.’

Want to keep up-to-date with our coronavirus coverage? Sign up to our newsletter.

Posted on 02 Sep 2020 Categories: Blog, Coronavirus, New economic models, Talking Points, The state we want