Beatrice Webb: a biography

Beatrice Webb lived many lives: debutante, social researcher, writer, political hostess and networker, poverty campaigner, pioneer of an independent Labour Party and, in her old age, polemicist and champion for the Soviet Union. Born into a mid Victorian upper middle class family, with a life of comfort and luxury, she turned her back on that world to become a social researcher, and gradually came to align herself with the labour movement. Her niece commented that she had spent the income derived from her father’s fortune trying to destroy the society on which it had been founded. In the years before the First World War Beatrice prepared the political and intellectual ground for what later became the welfare state.

“On the face of it, it seems an extraordinary end to the once brilliant Beatrice Potter (but it is just because it is not an end that she has gone into it) to marry an ugly little man with no social position and less means, whose only recommendation, so some may say, is a certain pushing ability. And I am not ‘’in love’ with him, not as I was. But I see something else in him (the world would say it was a proof of my love) – a fine intellect and a warm-heartedness, a power of self-subordination and self-devotion for the ‘common good’.”

(Beatrice Webb, diary, 20 June 1891)

“Presently there sailed into view, pedalling vigorously, a small beetle-like figure, crouched over the handle-bars of a bicycle made for two, and perched majestically behind him, what appeared to be a large grey bird.”

(Kitty Muggeridge, niece and biographer of Beatrice Webb, describing her first glimpse of Beatrice and Sidney, in 1915.)

“I refuse to be shut up in a soup kitchen with Mrs Sidney Webb.”

(Winston Churchill, 1908, on the possibility of his being appointed president of the Local Government Board.)

About Beatrice Webb

Beatrice was not a conventional feminist – she did not, for example, initially support the suffrage movement, and she refused to be channelled into working just on the position of women in the labour market. But she challenged Victorian concepts of class and marriage. Her unconventional marriage appears to have been happier than the conventional unions entered into by some, at least, of her sisters.

Her sisters ‘married well’, as expected of ladies of their class. In conventional terms, Beatrice did not. Instead, she formed a successful and long-lasting partnership with the impecunious and unprepossessing Sidney Webb, son of a London hairdresser. It was an extraordinary marriage – one biographer has called it “the most fruitful partnership in the history of the British intellect.” They collaborated on a series of major books, and in a wide range of public campaigns and roles.

In addition to the books she wrote with Sidney, Beatrice left a substantial literary legacy of her own: two volumes of autobiography and four volumes of published diaries – the first entry was made when she was fifteen, the last within weeks of her death, aged 85, in 1943. She describes her many lives in great detail and candour: her own emotions and her acerbic judgments of others are recounted alongside the political history of the period. She knew every Prime Minister in the first half of the twentieth century: she and Sidney visited them, and they came to dine at her table in London. One at least was so intimidated by her he did not even dare ask where the lavatory was in the Webb home.

Bertrand Russell once said that: “If you set down a list of Beatrice’s leading characteristics you would say – ‘What a dreadful woman!’ But in fact she was very nice. I had a great liking and respect for her. I was always delighted by a chance of meeting her.”

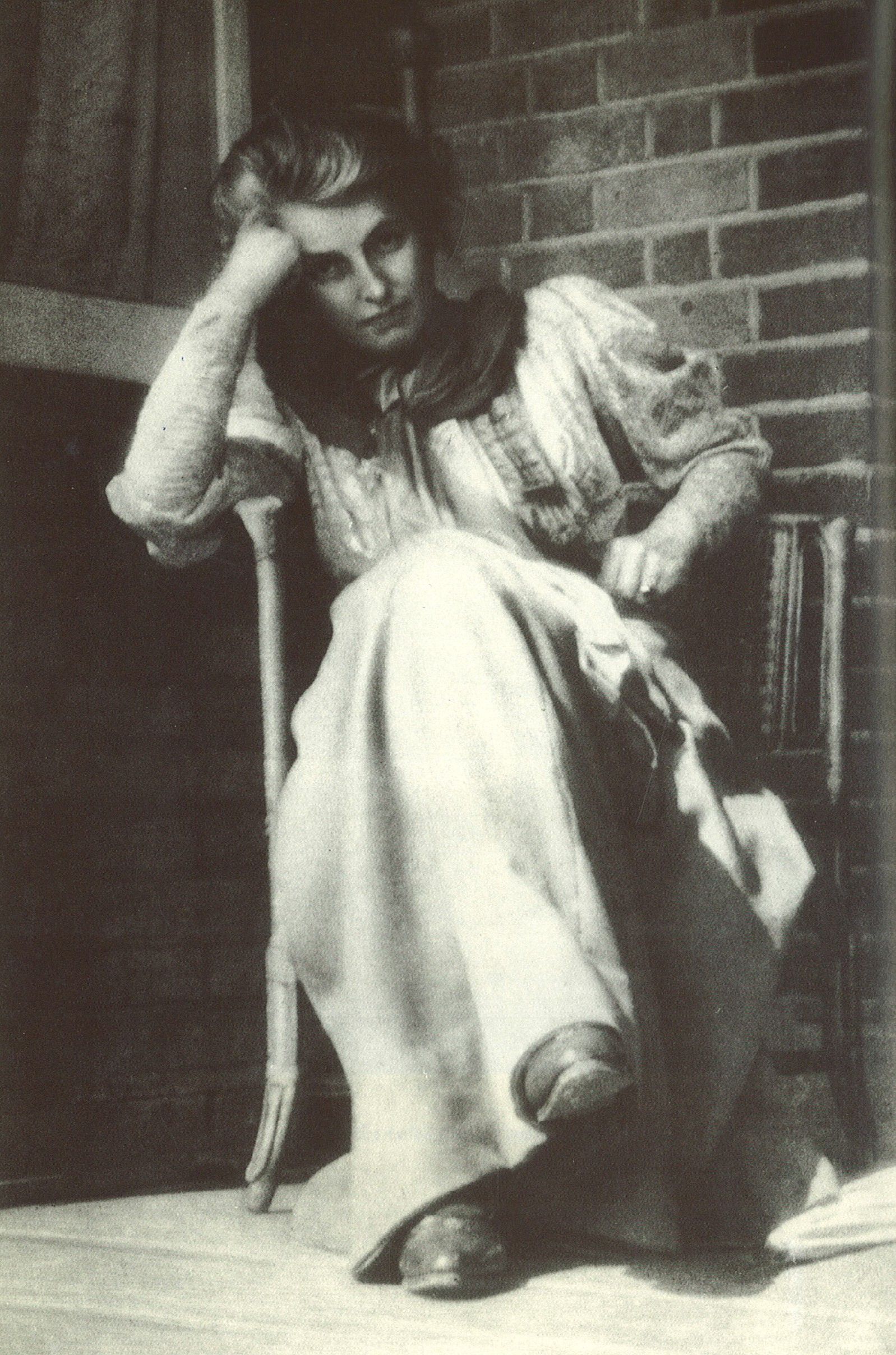

Beatrice Webb in childhood

Beatrice was a child of privilege: she was born in 1858, the eighth of nine daughters of Richard and Laurencina Potter – the only son died in infancy. Her relationship with her mother was not easy: Laurencina mourned the loss of the dead son, and Beatrice described her childhood as “creeping up in the shadow of my baby brother’s birth and death.” Her mother said that “Beatrice is the only one of my children who is below the average in intelligence.”

The family were prosperous business people; after early setbacks, Richard succeeded as a timber merchant and a railway director: he was a director of the Great Western Railway and for ten years also president of a Canadian railway company. Laurencina was the daughter of a Liverpool merchant, Lawrence Heyworth, whose own family had been weavers at Bacup in Lancashire. The girls grew up at Standish, their main country home, near Gloucester, but during the year would move around the country, not only to the family’s London homes, but to other Potter country houses, in Wales and in Westmorland. Their education was largely at home, with a series of tutors, although Beatrice spent a short period at a fashionable boarding school. The philosopher Herbert Spencer was a friend of Richard and Laurencina, frequently came to stay, and was a great intellectual influence on Beatrice. But at eighteen, wrote Beatrice later “I joined my sisters in the customary pursuits of girls of our class, riding, dancing, flirting and dressing up.”

Beatrice grew up in a world where she was surrounded by domestic servants; she relied on them all her life, realising when she was over eighty that she did not even know how to boil an egg.

The London Season was a prelude to courtship and marriage, and Beatrice’s sisters made the marriages expected of them – a business man, a banker, a doctor, a land owner, and an MP; two married barristers. When their father died in 1892, Beatrice was the only daughter still single. Their mother had died ten years earlier, and Beatrice had become, as she described it, her father’s “housekeeper and hostess”, taking charge of the household.

Not all the marriages of the other sisters were happy: the first husband of Rosie, the youngest, died of syphilis in 1896; the disease must have already been far advanced when they married in 1888. Another sister, Blanche, hanged herself in 1905, as her husband came to flaunt his commitment to a much younger mistress.

Growing involvement in social issues

Beatrice continued to manage the Potter household for the ten years between the death of her mother in 1892 and that of her father. But it was at this period that she developed her interest and involvement in wider social issues. Moving away from religion, she decided that “the most hopeful form of social service was the craft of a social investigator.” She began in 1882, with some work with the Charity Organisation Society (COS) – whose aim, in the words of Margaret Cole, later a biographer of Beatrice, was to “prevent the evils attendant upon undiscriminating almsgiving by systematic investigation and separation of the deserving sheep from the undeserving goats.”

Beatrice knew that some of her mother’s relations still worked at the mills in Bacup. With an old servant (a distant relative) she went, under an assumed name, to stay with her Lancashire cousins. She recorded her impressions in her diary, and in a series of letters to her father. Back in London, she next worked as a rent-collector and housing manager in Katharine Buildings, a block of working class flats in east London. Her housing work was interrupted by the need to go back to care for her father, who had suffered a stroke; after her sisters had organized a rota to care for him, she returned to London, this time as a researcher.

Charles Booth, the instigator and author of the Inquiry into the Life and Labour of the People of London, was a cousin, and Beatrice joined him in the spring of 1887, to make an investigation of dock labour in Tower Hamlets. This led, later in the same year, to her first published articles. Her next task for Booth was to investigate sweated labour in the tailoring trade; she worked undercover for a short period as a “plain trouser hand”. On the basis of this experience she gave evidence to a House of Lords Select Committee.

Booth, and the economist Alfred Marshall, would have liked Beatrice to go on to work more generally on the position of women in the labour market. She decided, however, to write a book on the cooperative movement instead, reading files and minutes and accounts, visiting cooperative societies, and interviewing leading co- operators.

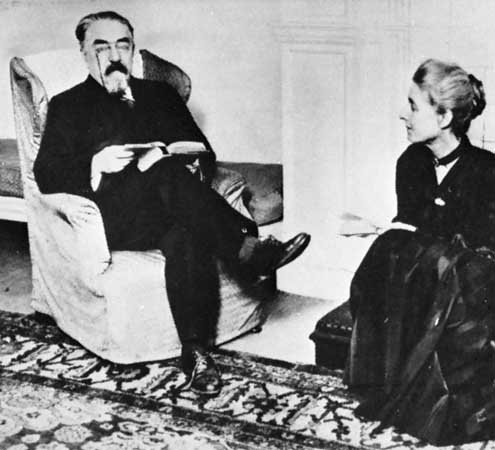

Beatrice Webb and Joseph Chamberlain

At the same time as she learned her trade as a social investigator, Beatrice fell overwhelmingly in love. In 1883 she met Joseph Chamberlain: twenty two years older than her, a Member of Parliament, and leader of the radical wing of the Liberal Party. He had been married twice; both wives had died in childbirth.

Her relationship with Chamberlain was a difficult one: he was attracted to her, but did not woo her. She was fascinated, perhaps obsessed by him. He explained bluntly to her that he tolerated no division of opinion in his household. She confided a great deal to her diary. In October 1884, she wrote “last of all came passion, with its burning heat, an emotion which had for long smouldered unnoticed, burst out into flame, and burnt down intellectual interests, personal ambition, and all other self developing motives.”

Over a period of four years there was a series of inconclusive and unsatisfactory meetings. In December 1886 she wrote in her diary “my intimacy with the great man brought about a deadly fight between the intellectual and the sensual, the sensual bringing forth the nethermost being and for a time overwhelming the higher part. But the intellectual has triumphed not by its own strength but by the force of circumstance; it has beaten the sensual and denied to it satisfaction.”

Had she married Chamberlain it would have been the ultimate ‘good marriage’. Beatrice may have been reflecting on her own experience when she wrote much later “the rumour of an approaching marriage to a great political personage would be followed by a stream of invitations; if the rumour proved unfounded the shower stopped with almost ridiculous promptitude.”

The relationship petered out, and in 1888 Chamberlain married for the third time. But echoes of the passion that had existed came back to trouble Beatrice for many years.

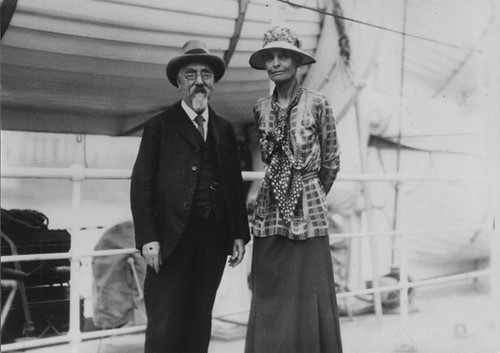

Meeting Sidney Webb

Beatrice arrived at London radical and Fabian politics via her social research, and so came upon the leading Fabian Sidney Webb, a close friend of George Bernard Shaw. In January 1890, when Beatrice and Sidney first met, he was still working as a civil servant. Sidney’s parents had sent him abroad as a boy to learn French and German – when at the age of 16 he came back to London, he continued to study at London evening institutions, passing a wide range of examinations – including the exam to become a First Class Clerk in the Colonial Office.

It was Sidney’s intellect, not his body, that Beatrice admired; in 1926 she wrote “With his big head, bulgy eyes, bushy moustaches and square-cut short beard…, small but rotund body, tapering arms and legs and diminutive hands and feet, he lends himself to the cubist treatment of the ridiculous.” She went on, however, to note how distinguished his head was: “This head-piece indicates brain power – a fine intellect tempered by visionary idealism and lit up with benevolence.” The contrast with Chamberlain was absolute – as Royden Harrison, a Webb biographer, wrote: ”The monocle and the orchid were more commanding than the pince-nez and the goatee.”

The courtship proceeded by fits and starts. For Sidney, it was love at first sight; Beatrice was far more hesitant, telling Sidney that nothing more than friendship and working collaboration was possible. In July 1890 they spent an afternoon in Epping Forest: “We talked economics, politics, the possibility of inspiring socialism with faith leading to works. He read me poetry as we lay in the Forest – Keats and Rossetti – and we parted.” By the summer of 1891, they were unofficially engaged – signified when for the first time Beatrice put her arm round him in a cab. The engagement remained secret during the last months of her father’s life.

Her friends and family did not approve of Sidney: Charles Booth told her “He is not enough of a man. You would grow out of him.” For Herbert Spencer, news of her involvement with Sidney meant that she was no longer fit to be his literary executor. Her sisters and their husbands were not enthusiastic.

Richard Potter died on New Year’s Day 1892; soon afterwards, Sidney and Beatrice announced their engagement; Beatrice went to stay with Sidney’s family for a week. Sidney, having resigned from the civil service, was elected to the London County Council (LCC), and they both began work on the history of trade unionism. They were married in a civil ceremony at the St Pancras Vestry on 23 July. They then went on honeymoon to Dublin, planning to study Irish trade union archives while they were there.

Beatrice wrote from Dublin to the best man: “We are very very happy, far too happy to be reasonable.”

“Together, we could move the world,” said Sidney. “Marriage is a partnership. It is the ultimate committee.”

Beatrice’s writing

Beatrice and Sidney Webb married with the intention of writing books together. Beatrice had her trade, as a social researcher, and completed her first book – on the history of the cooperative movement – before they married. (Sidney thought it had taken too long to write). From the Potter family fortune, they received a significant annual income – the capital was tied up for later generations. This income they used as a research grant.

They continued to write together for fifty years, gently satirized as the “two typewriters that clicked as one” – though in practice most of the manuscripts, at least in the early years, were in Sidney’s elegant handwriting. “Thick, heavy books poured from their pens,” writes David Marquand “– learned, solid, and mostly indigestible. Beatrice supplied the inspiration, Sidney the hard grind.”

They set up house in London, at 41 Grosvenor Road, now Millbank, not far from parliament. They did most of their writing there, working every morning, sat at opposite ends of the breakfast table, with a researcher to look up references and file away papers. For the final stages of a project they would go away to the country, at first to one of the Potter houses, until the text was complete.

Beatrice and Sidney had already begun the research for their History of Trade Unionism at the time of their wedding, and they continued it while on honeymoon. The result, published in 1894, was one of the first comprehensive histories of trade unions in any country. Its influence was great: Lenin and his wife Krupskaya, in exile in Siberia in 1898, translated it into Russian. Margaret Cole wrote that, when Beatrice and Sidney went to the Soviet Union in 1932, the name Webb “had an almost mystical prestige.”

Trade Unionism was followed in 1897 by two volumes on Industrial Democracy, describing what unions actually did – in providing insurance services for their members, in negotiating collective agreements, and in pressing for legislative change.

After the publication of Industrial Democracy, Beatrice and Sidney Webb moved on to the study of local government – exploring, in great detail, the evolution of local public services: markets and fairs, manors, boroughs and counties, highways and government grants. The project was interrupted many times – by service on Royal Commissions, by the First World War, by Sidney’s service as an MP and a cabinet Minister. The research was started in 1899; the last of ten volumes was published in 1929. In all, the work totalled over four thousand pages.

Their output was not confined to the big books: among much else, they continued to write Fabian pamphlets, reports, a proposed constitution for the Socialist Commonwealth of Great Britain, and a handbook for social researchers.

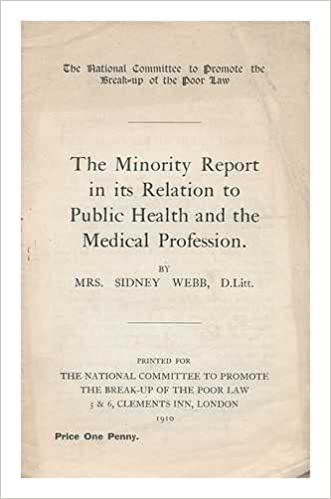

The Minority Report

Up to the end of 1905 it was Sidney, rather than Beatrice, who was in the limelight. He was a leading Progressive member of the London County Council, working with the Government to reorganise secondary and technical education in London; he had been a member of two Royal Commissions – on the Aged Poor, and on Secondary Education – and had given evidence to others. He was a Professor at the London School of Economics (which he had established), and sat on the Executive Committee of the Fabian Society.

But in December 1905 Beatrice was appointed by the outgoing Conservative Government of Arthur Balfour to be a member of a new Royal Commission on the Poor Laws. There had been no such review since 1834, when the New Poor Law had been inaugurated, based on three principles:

Less eligibility

The position of the poor person on relief “shall not be made really or apparently so eligible as the situation of the independent labourer of the lowest class.”

“Every penny bestowed that tends to render the condition of the pauper more eligible than that of the independent labourer is a bounty on indolence and vice.

The workhouse test

“All relief whatever to able-bodied persons or to their families, otherwise than in well-regulated workhouses… shall be declared unlawful and shall cease.”

The central authority

The establishment of a central board, with the power to make and enforce national regulations, and to group parishes into Poor Law Unions. This was the Poor Law Commission, which subsequently became the Poor Law Board and then the Local Government Board (LGB).

The Poor Law of 1834 was hated. Despite some administrative modification, it was still hated in 1905. The new workhouses had been christened the “Bastilles”. Edward Thompson called the New Poor Law “perhaps the most sustained attempt to impose an ideological dogma, in defiance of the evidence of human need, in English history.”

The 1905 Royal Commission was packed with defenders of the status quo ante – a block of senior civil servants from the Local Government Board, another block from the Charity Organisation Society. As soon as she had been appointed, Beatrice went to see the assistant secretary of the LGB, to find out the officials’ view of the purpose of the Commission. They were expected to propose some useful structural reforms: “But we were also to recommend reversion to the principles of 1834 as regards policy: to stem the tide of philanthropic impulse that was sweeping away the old embankment of deterrent tests to the receipt of relief.”

Beatrice fought this with every weapon at her disposal. She repeatedly challenged the Chairman of the Commission, and relentlessly cross examined the witnesses. She hired her own research team (with funds supplied by Charlotte, George Bernard Shaw’s wife). Margaret Cole says that “There is no doubt at all, in my mind, that Beatrice bullied and harassed her fellow Commissioner – and with intention.”

Beatrice seems to have quickly concluded that she would not be able to agree a single report with the majority of the Commissioners; by the summer of 1907, she had drawn up her own set of proposals, and had circulated them to leading Liberals and Conservatives.

In the event, when the Commission reported in February 1909, Beatrice and three other members produced a Minority Report of over seven hundred pages, providing a comprehensive alternative to the main report. While both reports advocated the abolition of Poor Law Boards of Guardians, Beatrice’s Minority Report called for the prevention, rather than the relief, of destitution. Poor Law services should be broken up and transferred to local government: children’s services to education, Poor Law health provision to the public health service, and so on. Part II of the Minority Report dealt with unemployment; like the Majority Report, it called for a national network of labour exchanges – but went on to call for Government taking responsibility for the organisation of the labour market so as to prevent unemployment. In the broad sweep of its proposals, the Minority Report foreshadowed the social reforms of the post 1945 era – the commitment to full employment, and the creation of a National Health Service.

To Beatrice’s surprise, the Majority Report received a favourable press: she had expected the Minority Report to be acclaimed at once as the better, more authoritative piece of work.

Beatrice then threw herself into campaigning for her proposals. With Sidney, she set up an organisation. They rented offices, hired staff, installed telephones, and published a monthly paper (The Crusade – forerunner of the New Statesman). At its peak, in November 1910, the campaign had over 30,000 members. They ran summer schools and huge national conferences. Rupert Brooke and Hugh Dalton leafleted Cambridgeshire villages from the back of a cart, while Clement Attlee worked in the office organising meetings.

And above all Beatrice Webb spoke at meetings – rallies – all over the country. “We are carrying on a ‘raging, tearing propaganda’, she wrote in her diary on November 14 2009, “lecturing or speaking five or six times a week. We had ten days in the North of England and in Scotland – in nearly every place crowded and enthusiastic audiences.” At the end of the month came “another two spells of lecturing – Sheffield, Leeds, Bradford and Hereford last week, Bristol, Newport, Cardiff this week, Worcester, Birmingham, Manchester next week – a wearing sort of life.”

The Webbs’ first biographer, Mary Agnes Hamilton, left an account of Beatrice speaking at one of these meetings, at the White City, in London: “She was magnificent in a great hat with ostrich feathers, and of course swept her audience with her moving picture of the morass of destitution. I thought her arguments a trifle on the unscrupulous side…”

But in spite of the campaign there was no legislation to implement the Minority Report. Instead, the Liberal Government, in the words of John Burns, the President of the Local Government Board, ‘dished the Webbs’, introducing contributory National Insurance against sickness and unemployment for parts of the work force, and a national network of Labour Exchanges to help deal with unemployment. The Parliamentary Labour Party, its leader J Ramsay MacDonald, and the leadership of the TUC, supported the insurance based approach, rather than the recommendations of the Webbs.

The Poor Law was still there after the First World War, but neither insurance nor the Poor Law could cope with the mass unemployment of the interwar years. Administration of the Poor Law was transferred to local authorities in 1929, but the Poor Law itself was only finally abolished in 1948, by a government whose leading members had campaigned for the Minority Report forty years before. By 1948, both Beatrice and Sidney were dead, but the welfare state was widely recognised as their legacy.

Beatrice Webb and private networking

Before Beatrice became a public campaigner she was a determined private networker. As her father’s hostess in the years after her mother’s death, Beatrice had moved widely in business and political society. “Huge party at the Speaker’s,” she wrote in her diary on March 1st 1883, “- one or two such would last one a life-time.”

When the Webbs married, George Bernard Shaw wrote to Sidney “I am seriously of the opinion that what is wanted is a salon for the cultivation of the Socialist party in parliament. Will Madame Potter-Webb undertake it?”

Undertake it she did, at 41 Grosvenor Road. Beatrice and Sidney set out to ‘permeate’ and influence the two existing political parties. The heyday of the salon was from the 1890s to the culmination of the Poor Law campaign in the years before the First World War. On the Conservative side Beatrice’s key links were with Arthur Balfour, Prime Minister from 1902 to 1905, and his brother Gerald, who served as president of the Local Government Board in his government. She flirted with Arthur, who she called (at least to her diary) Prince Arthur; she and Sidney stayed with Gerald and his family at their country home. The day before Beatrice’s appointment to the Poor Law Royal Commission was announced, Arthur came to lunch at 41 Grosvenor Road before they all went on to see Shaw’s latest play. Sidney worked closely with the Balfour government in reorganising secondary education.

Among the Liberals, Beatrice’s allies were the Liberal Imperialists, or Limps – the group within the party that supported the Boer War. These included her friend Richard Haldane (who much later became Lord Chancellor in the first Labour Government), HH Asquith, Prime Minister from 1908, and Edward Grey, who was Foreign Secretary in the Liberal Government. Her failure to build links with the Pro Boers, and in particular with David Lloyd George, Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1908, and one of the originators of National Insurance, later weakened the prospects of success for the campaign against the Poor Law. Another pro Boer was John Burns, President of the Local Government Board from 1905-1914. Burns was well known to the Webbs from the 1890s both as a trade unionist and a colleague of Sidney’s on the LCC, but there was little trust or warmth between them.

The entertaining was incessant. On 22 March 1907, for example, Beatrice wrote in her diary “A brilliant little luncheon typical of the ‘Webb set’. Dr Nansen (new Norwegian Minister), Gerald and Lady Betty Balfour, the Bernard Shaws, Bertrand Russells, Masterman and Lady Desborough – typical in its mixture of opinions, classes, interests – all as jolly as jolly could be, a rapid rush of talk.”

One Minister in the 1905 Liberal government who was not a Limp was the young Winston Churchill, who defected from the Conservatives, becoming President of the Board of Trade in 1908, and later Home Secretary. Meeting Churchill at dinner in the summer of 1903, Beatrice’s first impressions were critical – “egotistical, bumptious, shallow-minded and reactionary, but with a certain personal magnetism, great pluck, and some originality.” Later they worked together; in March 1908, Churchill met William Beveridge at dinner at 41 Grosvenor Road, following which Beatrice told him ‘if you are going to deal with unemployment you must have the boy Beveridge’.

HG Wells, who had been close to the Webbs, became distant from them on personal and political issues. He satirized Beatrice as “Altiora Bailey” (and her husband Oscar) in his novel “The New Machiavelli”. Altiora, he wrote “got together all sorts of interesting people in or about the public service, she mixed the obscurely efficient with the ill-instructed famous and the rudderless rich, got together in one room more of the factors in our strange jumble of a public life than had ever easily met before. She fed them with a shameless austerity that kept the conversation brilliant, on a soup, a plain fish and mutton or boiled fowl and milk pudding, with nothing to drink but whisky and soda, and hot and cold water, and milk and lemonade. Everybody was very glad indeed to come to that.”

But the ‘plunge into propaganda’ that followed the publication of the Minority Report meant a fundamental change in the Webb approach to politics. Churchill and his wife dined at Grosvenor Road again in October 1909: “He did not altogether like the news of our successful agitation. ‘You should leave the work of converting the country to us, Mrs Webb; you ought to convert the Cabinet.” The distance between the Webbs and the traditional political elite grew. In the summer of 1910, Beatrice wrote “We have been quite strangely dropped by the more distinguished of our acquaintances and by the Liberal Ministers in particular. I have never had so few invitations as this season.”

The Webbs continued to maintain contact with a wide range of opinion, and to entertain, almost to the end of their lives. In the early months of the First World War they were still dining with leading liberal Ministers.

The emergence of the Labour Party

But two aspects of the salon changed. First, Beatrice and Sidney became more and more focussed on the emergence of Labour as a party in its own right, rather than on influencing the Liberals and Conservatives. Beatrice told her diary in January 1918: “The policy of permeation is played out, and labour and socialism must either be in control or in whole-hearted opposition.”

After the War, Beatrice decided, in the words of Margaret Cole, “that the women of the Labour Party needed educating for politics even more for the men.” She set up the Half Circle Club, for the wives of trade unionists and Labour MPs “to be groomed and trained to play their part in public life.” Some of the intended beneficiaries appreciated this more than others; one group of dissidents established the “ant-Beatrice Society.”

But Beatrice and Sidney Webb were at the heart of Labour politics: inevitably, it was over dinner at Grosvenor Road, in December 1923, that the decision to form the first Labour Government was taken: Ramsay MacDonald wrote in his diary: “Met Clynes, Thomas, Henderson, Snowden and Webb at Webb’s. All agreed that we should take office.” Some of those who had “dropped” the Webbs a decade earlier now tried to “take them up” again.

The other change to the salon came after the First World War, with Beatrice and Sidney’s gradual move from Grosvenor Road to a house in the country, at Passfield, on the Surrey/Hampshire border. They bought the house in 1923, and moved there completely after Sidney left government in 1931. Invitations to lunch or dinner at Grosvenor Road were replaced by weekends at Passfield Corner.

Kingsley Martin, the editor of the New Statesman, wrote that the pilgrimage to Passfield Corner was sometimes exhausting: “You went down to tea where there were probably other guests. Serious talk began at once. The condition of the world and of the Labour and Socialist movement in particular, and immediate topics of the day, were systematically dealt with. One could almost hear Mrs Webb putting a mental tick after each item, when it had been discussed and nothing more of importance was likely to be said on the subject. The long, meaty conversation would continue at night by the fire.”

Margaret Cole also remembered those weekends: “No one who was a frequent guest at Passfield Corner during the ‘thirties can fail to retain a vivid recollection of Beatrice sitting on a low stool in front of the fire, her skirt pulled back and her stockings as often as not in wrinkles about her ankles, seeking information about current politics and current relationships… The tone of voice in which Beatrice could refer to some well-known figure as ‘an odious woman’ or ‘a very common sort of person’ will probably never be heard again in our lifetime. But it was all very enjoyable gossip, and did nobody any harm.”

On June 12th 1937 Beatrice and Sidney Webb gave a party at Passfield for over a hundred people. They invited all the descendants of Richard and Laurencina Potter, to the second and third generations, along with old friends like George Bernard Shaw and Beveridge. In the small hours of the morning after, Beatrice noted that it had been “an exhausting episode for the aged Webbs”. She thought that they would not run such a large party again.

But it had been ‘a decided success’ – “Dear old Father, how delighted he would have been at the thought of the successful careers of many of his descendants and their spouses. Three peers, four privy councillors, two Cabinet Ministers, two baronets and two Fellows of the Royal Society – a typical nineteenth- and twentieth-century upper middle class family, rising in the government of the country.”

The First World War

The First World War split the labour movement as deeply as it divided the rest of British society. Many members of the Independent Labour Party – including Ramsay MacDonald – opposed the war; many trades unionists supported it. Neither Beatrice nor Sidney was wholly in sympathy with either the pacifist or the patriotic camp.

Sidney’s position was the less complex: from the start of the war, he worked closely with the War Emergency Workers national Committee, a coordinating group, representing both political and industrial labour movement organizations, concerned with practical issues of the impact of the war on working people _ wages, prices, industrial relations, rents and conscription. Mary Agnes Hamilton describes this as the effort “to keep the party so hard at work on concrete, practical matters that the deep fissure of disagreement on the war itself never widened to become a lasting split.”

Beatrice, in contrast, was shocked and depressed by the war itself. In 1915 she was suffering from chronic sleeplessness. She wrote “the horror and terror of war eats into one’s vitality”. In 1916, she had a six month illness, which she described as a nervous breakdown, and attributed to “war neurosis.”

The horrors of war reached into her own circle: within the family network of the Potter sisters, three of her nephews were killed and four wounded – two of them severely. Another nephew, Stephen Hobhouse, was imprisoned as a conscientious objector. The young people of the generation who had supported the Campaign against Destitution were also casualties – not only Rupert Brooke, but others. In 1917, Beatrice noted in her diary: “The sustained horror of it is depressing. Friends lose husbands and sons; promising men, on whose career one had counted, are swept away.”

The balance of activity had changed again: it was Sidney who was busy on official committees, while Beatrice, in the war years, began work on what later became her first autobiographical book, “My Apprenticeship.” Only in the later part of the year was she invited to serve on official committees on post war reconstruction. She was told the story of her appointment by Tom Jones, former researcher on the Poor Law Royal Commission, now in Lloyd George’s Cabinet Secretariat. Going through the list of proposed members, the Prime Minister said: “Yes, we will have one of the Webbs… Mrs Webb, I think… Webb will be angry, Mrs Webb won’t.” Beatrice used her position on the Reconstruction Committee to reopen the question of Poor Law reform. The Committee recommended in favour of the 1909 Minority Report – but again, there was no legislation.

Sidney’s work on the War Emergency Workers National Committee brought him into close and regular contact with a wide range of Labour leaders, building mutual relations of trust and confidence. In addition, in 1915 he became a member of the National Executive Committee of the Labour Party, when the previous representative, WS Sanders of the Labour party, went off to war. In 1918, Beatrice commented that Sidney had become the “intellectual leader of the Labour Party.” In 1918, Sidney played a central part in drafting the new objectives and constitution of the Labour Party.

After the war, in 1919, Sidney was appointed an independent expert member of the Sankey Commission, set up to examine the future of the coal industry. Miners’ leaders observed his work, finding him a persuasive and compelling advocate for improved working conditions and nationalization of the mines. In particular, the Durham Miners, who had in the past elected long-serving union officials to parliament, concluded that they would be better served if someone like Sidney was one of their MPs. He was duly selected for Seaham in July 1920, following which Beatrice and Sidney spent long periods of time in the area, up to his election in 1922. They began by writing a History of the Durham Miners, and then organised local meetings. Jack Lawson, another Durham Miners’ MP, left a description of the campaign: “But there was one thing certain, and it was that Mrs Webb gripped the women much more than ever he did. There was the real stuff of the north when she addressed meetings and she left a memory that will never be forgotten by those now living.”

Sidney was elected MP for Seaham in October 1922, at the age of 63. He was at once put on the front bench, and a year later became President of the Board of Trade in the short-lived first Labour Government. He decided to retire at the age of seventy, and so did not stand at the 1929 election – his place at Seaham was taken by MacDonald. But when Labour then formed another Minority Government, MacDonald asked Sidney to become a peer, and return to the cabinet as Colonial Secretary. He became Lord Passfield; Beatrice, however, refused to be called Lady Passfield, remaining Mrs Beatrice Webb. She referred to Sidney as “The personage with the fantastical name of Lord Passfield.“ Curiously, Sidney held the same two cabinet posts as Joseph Chamberlain had held fifty years earlier.

Communism and the Soviet Union

“Old people,” Beatrice once said, “often fall in love in extraordinary and ridiculous ways – with their chauffeurs, for example: we feel it more dignified to have fallen in love with Soviet Communism.”

With the fall of the Labour Government, and the establishment of the National Government, Sidney’s involvement in conventional, parliamentary politics came to an end – to the great relief of both. When he came back to Passfield Corner Beatrice wrote that “He was exhausted, and rather upset by the queer end of the Labour cabinet – but delighted to be out of it all. “

Even though Beatrice and Sidney Webb were now in their seventies, however, their wider political activity did not cease. In 1929, the Labour Government had renewed diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union. The Webbs soon cultivated the new ambassador, Sokolnikov, inviting him and his wife first to dinner in London, and then for a weekend at Passfield Corner (where they introduced him to Philip Snowden, the grimly orthodox Chancellor of the Exchequer). Beatrice noted in her diary “We are the only ‘Cabinet’ members who have consorted with them. The Hendersons [Arthur Henderson was Foreign Secretary] do not ‘know them’ socially, nor the PM.” Sokolnikov encouraged the Webbs to visit Russia. By the time the Labour Government fell, Beatrice was determined to follow up the suggestion.

In September 1931 she wrote: “In the course of a decade we shall know whether American capitalism or Russian Communism yields the better life for the bulk of the people; whichever of these ‘cultures’ wins, we in Great Britain will have to follow suit.” But while Beatrice posed an open question, she already knew her own answer: “For without doubt we are on the side of Russia….”

Later in the 1930s, people on the left in Western Europe came to support Communism and the Soviet Union because they were seen as the only option against the totalitarian right: “Only the Communist party seemed unambiguously against Hitler and Fascism,” wrote Denis Healey. This was not the route by which the Webbs arrived at their interest in Russia. With many others, especially after the collapse of the Labour Government, they believed that the old economic order had failed, and that the Soviet Union, with its planned economy, was the only alternative on offer. Attending the Labour party Conference in September 1931, Beatrice noted that the prevailing spirit was a “dour determination never again to undertake the government of the country as the caretaker of the existing order of society.”

Over the winter of 1931/2, Beatrice and Sidney read extensively about Russia, hiring a translator to help with Russian language material. In May 1932, they sailed to Leningrad for a two month stay. Norman and Jeanne Mackenzie, the editors of Beatrice’s diaries, say that the visit “was very much the ‘managed’ tour that Beatrice had anticipated….they were taken on much the same round of schools, clinics, factories, farms and construction projects to the accompaniment of the same routine propaganda. Sidney’s notes suggest that they tried hard to get at the facts, but even such experienced investigators as the Webbs were not accustomed to guided tours and the practised defensiveness of Communist officials… their eager interest made them naïve if not completely gullible.”

Beatrice was unwell for part of the trip; she was looked after at a resort in the Caucasus while Sidney toured the Ukraine. Back in England at the end of July, they began to organise their material. Drafting the 1100 page book lasted through 1933 and 1934 and into 1935. In 1934, Sidney went back for a further visit. This time, Beatrice – now 76 – was not well enough for the arduous journey, and Sidney was accompanied by Barbara Drake, one of her nieces.

Beatrice noted in 1933 that their aim was “to give a vision of the Communist alternative to decadent capitalism – planned production for community consumption with as much liberty and equality as is compatible with the continued progress of the human race in body and mind and social life. “ She acknowledged, however, that “There is one dark spot – the lack of free expression among those intellectuals who are against the Communist creed and the practice thereof.”

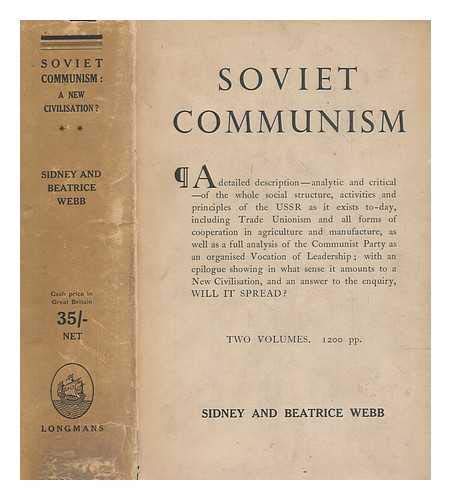

‘Soviet Communism: a New Civilization?’ was published in December 1935. A second edition (this time without the question mark) appeared in October 1937.

Kingsley Martin, editor of the New Statesman, described the two volumes as “monuments of industry, honesty, and disinterested labour. They are also about the most unrealistic books ever produced by able people. AJP Taylor wrote that ‘Soviet Communism’ was, “despite severe competition, the most preposterous book ever written about Soviet Russia.”

Beatrice and Sidney were not alone in the 1930s in looking to the Soviet Union as a beacon of hope. With Healey, many saw communism as the only force that could effectively challenge fascism.

But when the first edition of the book was in preparation, its authors had to ignore the evidence of famine and oppression. By the time of the second, they had to ignore – or worse, justify – the purges and the show trials.

The death of Beatrice Webb

The Soviet Union was Beatrice’s last great cause. She continued to speak and write on the subject, and travel from Passfield to London. Sidney suffered a stroke in 1938; while he made a substantial recovery, he could not travel far. They continued to welcome visitors until shortly before her death at the age of 85 in 1943.

Sidney died in 1947. Although they had agreed that their ashes should be buried at Passfield, at the suggestion of George Bernard Shaw they were re-buried in Westminster Abbey in December 1947 – the only married couple to be honoured in this way.

The address was given by Clement Attlee, the Prime Minister, who said: “Millions are living fuller and freer lives today because of the work of Sidney and Beatrice Webb.”

Only one of the Potter sisters, Rosy, the youngest, was still alive. As the two caskets were being put in place, she whispered hoarsely “Which is Sidney and which is Beatrice?”