‘Sorry we missed you’ reveals the sorry state of our society

Posted on 15 Jan 2020 Categories: Blog, Books and films, Social Security, The society we want, The state we want

by Barry Knight

‘I feel in complete shock. At the end I thought my heart had stopped.’ So read a text sent by a friend of mine as she left the cinema having watched Ken Loach’s latest film Sorry we missed you.

The film tells the story of a delivery worker on a zero hours contract in the ‘gig economy’. Ricky (played by Kris Hitchen) is a former construction worker in Newcastle who lost both his building work and his chance of a mortgage after the economic crash of 2008. He is renting with his wife Abbie (Debbie Honeywood), a contract nurse and in-home carer who visits disabled, elderly and vulnerable people every day for their meals, baths and ‘tuck-ins’.

Ricky aims to better himself by becoming a self-employed delivery driver for a big company, dreaming that, if successful, the family will be able to buy their own house. He has to buy or lease his own van, or rent one from the firm at an extortionate daily rate, and meet strict targets for deliveries – set by the all-important scanner. Timing is everything, so Ricky has no time for loo breaks and has to carry an empty plastic bottle with him.

Ricky persuades Abbie to sell the car she uses for work so he can buy a van. Abbie, also on a zero hours contract, has to take the bus to meet with her clients and she has to spend longer and longer to finish her rounds.

Neither parent has much time to spend with their children – Seb (Rhys Stone), a difficult teenager with artistic talent but in trouble with the authorities, and his delightfully smart younger sister, Liza Jane (Katie Proctor). Family life becomes strained and fractious.

These fragile arrangements unravel when Ricky has to take time off work when Seb gets into trouble with the police. He is ‘sanctioned’ by his employer and fined so that he gets into debt with the firm. Working ever harder to keep up, one bad thing follows another and Ricky ends up in hospital. The company demands more money because of his failure to turn up for work. The family implodes and at the end it seems likely that they will lose everything.

Fact or fiction?

The film reflects the reality of life for many in modern Britain. According to the Office of National Statistics, there were over 1.8 million zero hours contracts in 2017. This compares with fewer than 200,000 ten years earlier.

Robert MacDonald, from Teesside University, says Ken Loach’s new film on the gig economy tells exactly the same story as our research. The research shows ‘the low-pay, no-pay cycle’ in which people churn from ‘one shit job to another shit job’, interspersed with periods of unemployment. When people are unemployed, they face the problems of a cruel welfare system as set out in Ken Loach’s previous film, I, Daniel Blake.

As things stand, there are few prospects of improvement. The Resolution Foundation assessed the manifestos of the three main political parties for the 2019 general election. It found that none of them would reduce child poverty. As the foundation puts it: ‘We forecast that under current policy plans (i.e. the Conservative package) child poverty will rise from 29.6% in 2017-18 to 34.4% in 2023-24.’ At the same time, the report says: ‘Labour’s plans would see child poverty remain roughly the same, with a rate of around 30.2% in 2023-4.’ The figure under the Lib Dems’ plans would be 29.7 per cent in 2023-4.

The film is an iceberg

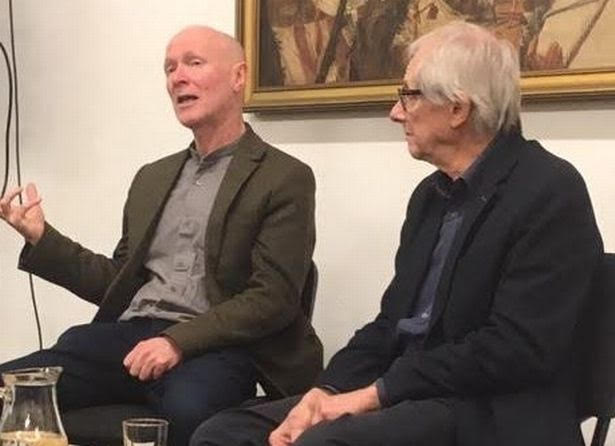

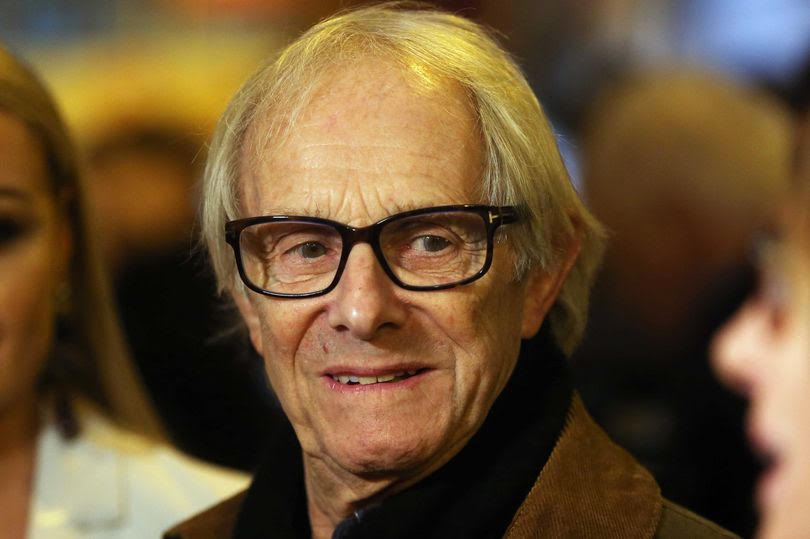

The film formed the background for a public discussion with Ken Loach and screenwriter Paul Laverty at the Lit & Phil in Newcastle on 4 December 2019. Some 250 people packed into a conference room for a discussion planned for 90 minutes but which was so lively that it overran by 15 minutes.

Ken Loach opened the discussion by saying: ‘A film is like an iceberg. What lies under the surface is as important as what you see above it.’

The discussion took this as a cue, and focused on how we have allowed such a cruel economy and social security system to come about. And why is there so little outcry about it? The subsequent discussion revealed that answers to the two questions are related: the changes have been taking place gradually over a long period and we have become acclimatised to the hostile reality, believing it to be our fault. As Ken Loach put it: ‘While the notion of the gig economy is a new one, its arrival is the tail end of many, many decades of how our reality has changed.’ Specifically he was referring to the Ridley Plan by then Conservative minister Nicholas Ridley, which he began compiling after his party’s humiliating defeat in the miners’ strikes of the early 1970s.

The ‘gig economy’ has a long provenance

The Ridley Plan was designed to prepare the ground for privatisation ‘by stealth’. This involved introducing market measures in running nationalised industries, and fragmenting the public sector into independent units that could later be sold off. Integral to the Ridley Plan was, as Laverty put it at the meeting, ‘to smash the trade unions’. In Ridley’s view, trade union power in the UK was interfering with market forces and causing inflation, and therefore had to be checked to restore the ‘profitability’ of the UK. He and others also saw it as necessary to check union power in the aftermath of their challenge to the Heath government in the face of the 1973-4 strikes.

Ridley suggested contingency planning to defeat any challenge from trade unions:

- The government should if possible choose the field of battle.

- Industries were grouped by the likelihood of winning a strike; the coal industry was in the ‘middle’ of three groups of industries mentioned.

- Coal stocks should be built up at power stations.

- Plans should be made to import coal from non-union foreign ports.

- Non-union lorry drivers were to be recruited by haulage companies.

- Dual coal-oil firing generators were to be installed, at extra cost.

- The money supply to the strikers should be cut off, making the union finance the strikes.

- A large, mobile squad of police should be trained and equipped, ready to employ riot tactics in order to uphold the law against violent picketing.

These tactics were successfully employed during the miners’ strike of 1984-5, when the National Union of Mineworkers was defeated by the Conservative government of Margaret Thatcher. The report had been leaked six years before by The Economist and published on 27 May 1978, but the unions, especially the NUM, showed no interest in adapting or altering their own tactics in response.

According to Ken Loach and Paul Laverty, Labour colluded with the government. Labour leaders Neil Kinnock and Roy Hattersley were ‘missing and didn’t want the miners to win’. Historian Selina Todd agrees, suggesting that their motivation was based on their desire to appeal to the middle class. She writes:

‘Meanwhile, where was Labour? After a brief swing to the left in the early 1980s, Neil Kinnock had taken charge of the party in 1983. Kinnock argued that Labour had to “adjust to a changing economy” by appealing to “a changing electorate”, including the docker … who owns his own house, a new car, microwave and video, as well as a small place near Marbella”. “Labour”, argued frontbencher Michael Meacher, needed to recruit “the technocratic class – the semi-conductor chip designers, the computer operators, the industrial research scientists, the high-tech engineers – who hold the key to Britain’s future … The growing underclass of have-nots, large and desperate though it is, can only in the end come to power through policies that assist, and are seen to assist, the not-so-poor and not-so-powerless.” Unsurprisingly, given such sentiments, the national party offered lukewarm support to the NUM during the miners’ strike of 1984-5.’(1)

In part, Labour’s actions – or lack of them – were influenced by the decline in working class power.(2) During the 1970s governments had concluded that profit-making and people’s welfare were ultimately irreconcilable – a conclusion made starker by the oil crisis and its repercussions. Faced with the choice, they chose loyalty to those who held economic power: industrialists, businesses and financiers. The major political parties were united in viewing working class power as a threat to democracy rather than a prerequisite of it. Their decision to govern in favour of capitalists rather than in the interests of the majority of the electorate was an enduring legacy of the 1970s.

Todd also points out that the political attitudes of the population changed during the 1970s.(3) Rising unemployment and economic insecurity had increased people’s desire to exert more control over their lives, but the collective approach to achieving this – through trade unionism, women’s groups and tenants’ campaigns – had apparently failed. In 1979 Margaret Thatcher won the general election on a promise to give voters the control over their lives that Labour had failed to deliver. Her brand of Conservatism promised an individualistic freedom, predicated on the myth that everyone could exercise equal choice in a free market. This proved to be an alluring message. Labour’s weak response to it only strengthened the Prime Minister’s case that there was no alternative to the free market. Two years after her 1979 victory, Margaret Thatcher gave an interview to the Sunday Times in which she said: ‘Economics are the method: the object is to change the soul.’

According to Selina Todd, she succeeded:

‘Generations who had grown up in the individualistic 1980s and 1990s were even more convinced that they were responsible for their circumstances.’(4)

And:

‘By 2010, people were less likely to see class and inequality as a means of making sense of their circumstances.’(5)

The consequence is that:

‘In failing to acknowledge economic inequality as a problem, some people blame “scroungers” or immigrants for their difficult circumstances, some blame their middle-class neighbours – but more blame themselves.’(6)

A changing labour market

Just as privatisation was enacted over several decades, and changes in attitudes took years to take root, so did the evolution of the labour market that allows zero hours contracts.

There are two key interrelated factors involved here. First, global trends and information technology have stripped away ‘Fordism’, with its well-paid jobs and career structures in hierarchical organisations. Second, governments since 1979 have sought to deregulate the labour market, believing that flexible employment is necessary for productivity.

Taking the global trends first, the past 30 years have seen big changes in economic organisation and the way that labour is deployed. In the 1990s management theory promoted a flatter structure in organisations. This was achieved by a reduction in the number of layers in the management hierarchy with the goals of bureaucracy busting, faster decision making, shorter communication paths, stimulating local innovation and a high-involvement style of management. Cutting out unnecessary layers also reduced costs.

Delayering was also made easier as the economy transitioned from one based largely on manufacturing to one based mainly on services. The growth of technology means that jobs that people once did are increasingly performed by machines, which requires fewer people. Technology, combined with a desire to cut labour costs, has also led to the tendency for firms to contract out work to people who are self-employed and can work from home.

These changes have reduced the number of ‘good jobs’ in which people can draw salaries for life. Technology has meant that many skilled trades have disappeared and the idea that people can have a 50-year career in one firm is gone forever. The name of the game is ‘flexibility’.

This brings us to the second strand: official encouragement of the flexible labour market over the past 40 years. The Conservative governments from 1979 took a step-by-step approach to weakening both the collective and individual rights of workers, beginning with Employment or Trade Union Acts in 1980 (Prior), 1982 (Tebbitt), and 1984 and 1988 (Fowler). These developments are set out in the excellent chronology of the Institute of Employment Rights. By 1990, the process of deregulation and enforcement of ‘flexibility’ were well-advanced.

The Labour governments from 1997 continued the process. As part of his reform of public services, Tony Blair introduced a new employment structure to the public sector stressing job flexibility; he also introduced payment by results.(7) The policy was designed to end fixed salaries, job tenure and promotion structures, which were regarded as ‘restrictive practices that hamper productivity’.

The overall effect of the past 40 years has been to weaken the power of labour as a factor of production and to enhance the role of capital. This has been particularly noticeable in the past 10 years. In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, which was caused by the reckless behaviour of bankers and financiers, the people who have suffered most are those who work for a living. Wage rates have remained largely static. There are few jobs that offer prospects of advancement, and the prospects for young people are bleak. The fastest growing category of people in poverty is those who are in work.

What is to be done?

There are no quick fixes to the problems we face. This is all the more obvious when considering that the film depicts a story that has been more than 40 years in the making.

What Ken Loach and Paul Laverty suggest is that we need a new narrative to unite us and put to bed the fractious nature of our politics. Over the next year, Rethinking Poverty will aim to create that narrative, bringing together people from different perspectives who wish to see new ways of deciding and doing things in our society.

This will entail finding a new operating principle for society. It has to start from the premise that the economic system that has dominated the world for the last 40 years is broken and cannot be repaired.

We can take heart from a newly opened ‘Museum of Neoliberalism’ in London. It has a brilliant exhibition, including the machine Amazon workers have to wear in the giant warehouses or ‘fulfilment centres’ which monitors their every move and records their every toilet break.

In our work, we can draw inspiration from the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg. When I visited the museum in 2014, I was delighted to see the strap-line ‘Apartheid is now where it belongs – in a museum’. Our goal should be to be able to say the same for neoliberalism.

- Selina Todd (2014) The people: the rise and fall of the working class, 1910-2010, London: John Murray, p 333

- Todd, p 314

- Todd, p 314

- Todd, p 356

- Todd, p 355

- Todd, pp 355-6

- Prime Minister’s Office of Public Services Reform, Principles into practice, 2002

Want to keep up-to-date with more articles like this? Sign up to our newsletter.

Posted on 15 Jan 2020 Categories: Blog, Books and films, Social Security, The society we want, The state we want