Transforming markets: why markets need a makeover

Posted on 13 Jan 2022 Categories: Blog, Climate crisis, New economic models, Community Wealth Building, Our vision, The business we want

by Barry Knight

If Martians landed on Earth tomorrow, they would be surprised by many things, but they would be shocked by an economic system that allows a few billionaires to play in space while ordinary people queue around the block for food banks. Over the past 40 years, a market-based society has consistently funnelled wealth to the top. The pandemic has accentuated such trends. The 1 million US billionaires have become $12 trillion richer as a result, while many workers have gone hungry. This is a serious indictment of the way markets work. Anyone asking, ‘how do we make markets work for the common good?’ or ‘how do we go about transforming markets?’ has much work to do.

In this article, we start by describing a period in history when markets were quite effective in supporting the common good. We then identify what went wrong and why, assess the dimensions of the problems that reformers now face, and suggest the kinds of changes that would enable the mass of people to live flourishing lives.

Markets working for the common good

There was once a time when markets played a useful role in promoting the common good. During Les Trente Glorieuses from the mid-1940s to the mid-1970s, the application of the ‘general theory’ of John Maynard Keynes led to a mixed economy in Western Europe, increasing both prosperity and social security. Post-war government policies in many countries were designed to banish the excesses of capitalism that had led to the crash of 1929 and the subsequent great depression in the 1930s.

Writing in 1956, Anthony Crosland claimed that capitalism had been tamed. Private industry had reined in the profit motive in favour of a desire for collective wellbeing, while governments were willing to step in to help people in the event of market failure. Crosland’s work was highly influential and governments felt free to relax their controls.

Markets failing the common good

This was a mistake. The oil crisis of the mid-1970s led to ‘stagflation’ – zero growth combined with rampant inflation. Market intervention and social responsibility, ideas central to Keynes, were abandoned and replaced by the free-market ideology of Milton Friedman. Neoliberalism was born – a philosophy expressed in ten words: free markets, small state, low tax, individual liberty and big defence. According to Friedman, business had no place in creating social progress:

‘There is one and only one social responsibility of business – to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits.’

As private profit replaced societal wellbeing as the superordinate force in markets across the world, the balance of power in the economy shifted from labour to capital. Widespread deregulation of capital controls meant that money could move seamlessly across borders, while the bargaining power of labour in the economy was weakened by legislation to reduce trade union power.

This new philosophy brought economic growth and rising living standards. However, rewards were unevenly distributed, so that in 1977 the Gini coefficient began its inexorable rise across the globe as social and economic processes began to follow the ‘greed is good’ mantra spouted by Gordon Gekko in the 1987 film Wall Street.

The consequences now lie before us. A world obsessed with economic growth has led to environmental degradation, the removal of social safety nets, deregulation of planning controls, fragmented communities, a restless and insecure workforce, increased conflict, an inability to deal with systemic racism, and the rise of political leaders who exploit discontent for their own narrow purposes. This leaves the world in a precarious state and many people fear the collapse of global systems.

All this was foreseen. The 1972 Club of Rome Report Limits to Growth predicted that the emphasis on economic growth in a world of finite resources would lead to the collapse of civilisation. Recent data analysis by Gaya Harrington has confirmed the bleaker scenarios set out in the report. Evidence of climate catastrophe is all around us with wildfires in the US and Siberia, floods in Germany, and reports that the Amazon rainforest can no longer function as a carbon sink.

The social consequences of growth have been equally dramatic. The pursuit of profit has hollowed out the labour market with adverse consequences for society. The drive to reduce overheads in organisations has led to the delayering of hierarchies, the replacement of workers by computerised technology and the deskilling of tasks.

The process has led to a low-wage economy in which many workers have no job security. We now have what is often called the ‘gig economy’ in which people are self-employed and work on a short-term project basis. Alternatively, people are often doing what David Graeber called ‘bullshit jobs’ – performing tasks that are so pointless and unnecessary that the person doing the work suffers psychological humiliation that devalues their sense of self-worth.

This hollowing out of the labour market has led to a new class of insecure people. Guy Standing called this group the ‘precariat’. He suggested this was a ‘dangerous class’ because its sense of anger and loss leads to a revenge psychology in which they blame people even weaker than themselves such as migrants and minorities. Feeling powerless makes them susceptible to the siren calls of political extremism whose dramatic rise can be traced to underlying economic conditions.

Transforming markets: a huge task

The world now faces a comprehensive mess, covering the environment, society and politics. The damage all appears to be self-inflicted, and to have a common root in our allowing markets to have free rein over the past 40 years.

To address this, there is now a growing consensus among people working in philanthropy and civil society that what is needed is wholesale systems change, because it is increasingly clear that the old solutions are no longer available. A return to the mixed economy of les Trente Glorieuses is impossible as the rise of extremism has destroyed the centre ground in politics that enables the compromises necessary to develop it. John Gray has pointed out that liberal elites are ‘looking on blankly as the world they have taken for granted slips into the shadows’.

We cannot expect the markets to reform themselves. It is unlikely that the underlying cause of the problem will suddenly decide to change its ways and become part of the solution. After all, Adam Smith’s ‘invisible hand’ is made up of billions of individual choices in many different places that defy coordinated logic. Markets operate on the basis of supply and demand and have scant relationship with moral purpose. Michael Sandel has shown how markets have permeated every aspect of life, undermining our sense of value.

The idea of the market is now embedded in our collective psyche. In The century of the self, filmmaker Adam Curtis shows how, since the First World War, the tools of psychoanalysis have been used to develop mass manipulation to create a market-based society in which people buy things that they don’t need or even want. The architect of propaganda was the nephew of Sigmund Freud, Edward Bernays, who wrote in 1928:

‘The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society. Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country. We are governed, our minds are molded, our tastes formed, our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of.’

According to Mark Fisher in Capitalist Realism, ‘It is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism’. The sheer inventiveness of the market is able to outrun its discontents so that vigorous criticisms from Nirvana to Hunger Games are transformed by the smooth logic of capitalism into its very products for sale. Likewise, acts of subversion, resistance and even protest are absorbed and re-presented not as attempts to develop alternatives, but as parts of the capitalist conversation open for negotiation only in its own language. It is small wonder that all the effort to reform the market through corporate social responsibility has had little effect. Taming the market from within is like trying to stop a tiger from attacking you by offering it sweets.

The alternative

Rather than fixing a broken model, we need to build a new one. If we are content to tweak the existing system, we will soon be witnessing the simultaneous end of capitalism and the world as we know it. The environmental crisis will see to that.

To prevent what Guy Standing calls the ‘politics of inferno’, we must move to a ‘politics of paradise’, in which redistribution and income security are reconfigured in a new kind of good society, and in which the fears and aspirations of the precariat are made central to the agenda. In all of this, the needs of the environment must be front and centre because we cannot continue with business as usual.

The good news is that there are alternatives and we must fast-track them so that they become mainstream. Such alternatives have a long history – going back at least as far as Robert Owen’s forming of cooperative communities in the early 1800s – and have gained in prominence since the publication of E F Schumacher’s Small is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered in 1973.

This inspired a collection of essays edited by Paul Ekins called The Living Economy, which set out practical methods to implement a green economy. The Other Economic Summit (TOES) was held in 1984. This was a counter-summit to the annual G7 meeting. It included diverse groups of economists, greens and community activists. TOES eventually became an umbrella term and similar meetings were organised around the world for the next two decades.

The New Economics Foundation was formed in 1986 by TOES to advance the cause. It has three main priorities:

- A new social settlement to ensure that people are paid well, have more time off to spend with their families, and have access to the things we all need for a decent life.

- The Green New Deal: a plan for government-led investment to reduce the carbon we emit and massively boost nature, while creating a new generation of jobs.

- The democratic economy to devolve state power and transform ownership of the economy to give us all an equal stake in the places where we live and work.

These developments laid the ground for others to develop initiatives such as the social economy, the circular economy, the doughnut economy, community wealth building and other similar ventures. All these have Schumacher’s subtitle ‘economics as if people mattered’ at the front of mind while being self-consciously environmentally friendly in their approach.

A range of organisations have pursued this agenda across the world and have begun to see successes in some places. A remarkable one is the ‘Preston model’ developed with CLES in which a run-down place was regenerated based on community wealth building. This involves enhancing assets that already exist within the community and ensuring that they have a positive multiplier effect on local jobs, wellbeing and health. In 2018, Preston was named the ‘Most Improved City in the UK’.

Alternatives remain marginal

While gaining ground, initiatives such as the Preston model are still not part of mainstream economic thinking. There is no clearer evidence of this than a radio programme at the height of the pandemic in which Mark Mardell interviewed the world’s leading economists. All proposed ideas to restore the normality of markets and a return to growth, rather than taking the opportunity to build a new world based on environmentally sensitive policies such as the Green New Deal.

The myopia of leading economists is matched by the world’s elites who benefit so much from the chaos and are poised to embrace what Naomi Klein has called ‘disaster capitalism’. Governments go along with this because, not only are they paralysed by the pandemic, but they have few constructive ideas for a better world and are content merely to shore up the existing system by looking after the interests of the rich and powerful in ways that enable them to hold on to power.

The awakening

There is growing recognition that our flawed societies stem from economic tramlines we have been travelling on for decades. We now see that the destination marked ‘economic growth’ is taking us in the wrong direction. The problem is that we are so far along that we are close to journey’s end. Only a rapid transformation will save us. The only answer for some is ‘degrowth’.

The question is where is such a transformation going to come from? The only realistic hope is for a change in human consciousness. We need to wake up from the blindness of what E F Schumacher called ‘materialistic scientism’. This is a world view that uses logical positivist strands of thought alongside Newtonian physics to cast nature as an object to be exploited for human ends. Seeing material reward as the goal for a human life results in measuring success against concepts such as gross domestic product. While research always finds a statistically significant correlation between wealth and happiness, it is a weak one. Aaron Ahuvia has reviewed the evidence and found no study in which measures of wealth explain more than 5 per cent of the variance in measures of happiness. Moreover, most of the relationship is found at the bottom end of the distribution – as increased income reduces the unhappiness of people on low incomes.

Both left and right positions in politics have traditionally used materialistic advance as the engine for human wellbeing. The problem is that economic analysis based on this premise casts people in a passive role. As historian E P Thompson has pointed out, the left in politics sees people as victims of oppression in an unsympathetic system, whereas the right sees people as units in a labour market. Either way, this demeans humans by downplaying their agency and creativity, while manipulating them by encouraging them to buy shiny goods to keep the machine running.

Changing the paradigm

It is imperative that we change the priorities for our society. This involves a shift away from seeing wealth as the touchstone of success to prioritising a state of wellbeing in which people feel in control of their lives. This requires a change of mindset because, as Donella Meadows, lead author of Limits to Growth, pointed out half a century ago, deep change depends on new ways of seeing. The most difficult and most effective point of intervention is to shift the mindsets and paradigms that underlie behaviour. These are the most deeply held beliefs that drive a system or were used to design it.

Graphically, the model can be set out as the ‘systems iceberg’. First developed by Edward T Hall in 1976, this looks at how various elements within a system – which could be an ecosystem, an organisation, or something more dispersed such as a supply chain – influence one another. A systems approach sees day-to-day problems as a reflection of deeper factors.

The mental models at the bottom of the systems iceberg have a profound effect on what happens in the system. This is because of what cognitive scientists call the ladder of inference: the way that mental models affect the way that we take decisions about action in the world.

Without a mental model possessed by a deep sense of underlying values, we are always prone to backsliding. As an example of this, critics of the September 2021 trade deal between the UK and Australia have suggested that UK government ministers would never have dropped ‘climate asks’ to get the deal ‘over the line’ had it had a genuine commitment to the Paris Agreement.

The new paradigm

So, what would a new paradigm look like? This cannot be set out by a single person because, if we are to fulfil Guy Standing’s criteria for the ‘politics of paradise’, it requires a process which is inclusive of people who are part of the precariat.

Notwithstanding this qualification, in this section I will set out some first thoughts based on the conversations I have held over the past 18 months with people from across the globe who wish to see a better world. Rather than thinking about this as ‘fixing a problem’, we need to develop a new way of seeing requiring a leap in moral imagination that cascades through participants in the process and filters through to social attitudes in society. The process is less about the use of discursive logic and more about the heart’s imagination.

To build a new economy that is suitable for the 21st century and beyond, we cannot start with economics. Lionel Robbins’ classic definition of economics as ‘the science that studies human behaviour as a relationship between ends and scarce means which have alternative uses’ rules out what really matters to people – leisure, knowledge, friendship and other goods that have no price. The principle of scarcity means that society is always in deficit. The answer to scarcity is always ‘more growth’, yet scarcity always remains, demanding yet more growth.

However, in any system, we need to ask, how much is enough? Maslow’s hierarchy of needs suggests that once we have satisfied our basic needs for food, safety and shelter, we move on to higher things like love and belonging, esteem and self-actualisation. However, the lingering sense of scarcity means that we think that five-star hotels and limousines are part of our basic needs.

Ancient philosophy has much to teach us here. For example, the highest good for Aristotle was ‘eudaemonia’– roughly translated as ‘flourishing lives’. In his view, money was a means to this end and not an end in itself. The extensive population research for Rethinking Poverty found that people’s sense of a good society was driven by social factors – most notably the quality of their personal relationships with family, friends, neighbours and others – and not by economic factors, including how much money they had.

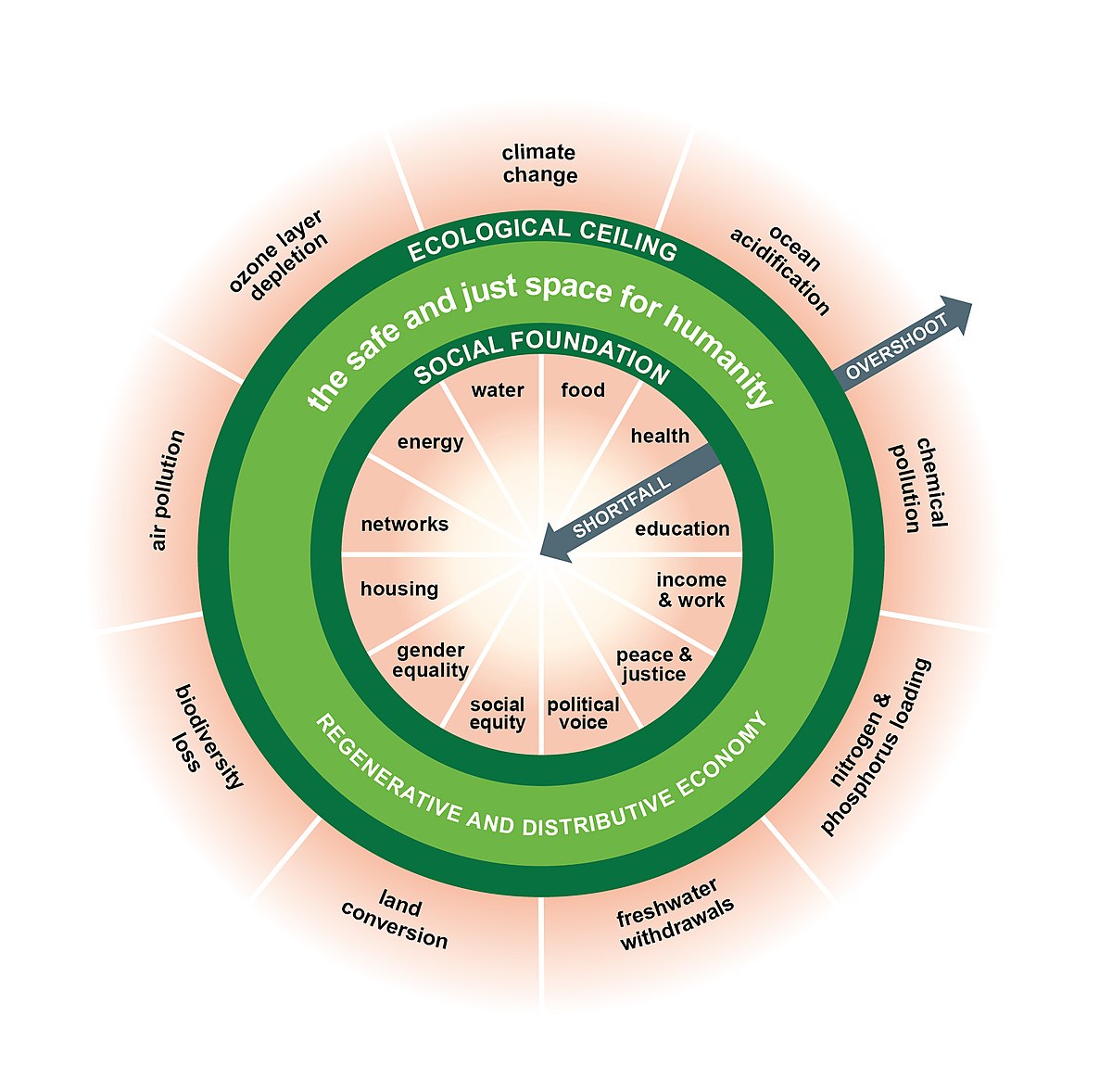

This chimes with other research and gives important clues to how we should organise our economy. According to Kate Raworth in her influential Doughnut Economics, this calls for another Aristotelian concept – balance. If we conceive the economy as a doughnut, we should ensure that the doughnut has an inner layer, ‘a social foundation of well-being that no one should fall below’, and an outer layer, ‘an ecological ceiling of planetary pressure that we should not go beyond’.

This perspective is in tune with nature. Human beings are part of the ecosystem and not separate from it. It follows that human agency needs to be part of the regenerative process that nature has at its heart. As William Morris, who inspired the arts and crafts movement of the 19th century, put it:

‘… everything made by man’s hands has a form, which must be either beautiful or ugly; beautiful if it is in accord with Nature, and helps her; ugly if it is discordant with Nature, and thwarts her; it cannot be indifferent …’

On this account, work is a creative, regenerative and dignified endeavour. Keynes saw this higher purpose of work. He may have lived most of his life in the nether regions of capitalist action, but he always had one eye on the heaven of art, love and the quest for knowledge. Such a perspective has been lost in recent times, though John Cruddas has recently updated this vision in his book The Dignity of Labour in which he argues that work must give our lives meaning, rather than being tedious drudgery.

Transforming markets

The key question to emerge from the above analysis is, ‘how do we make markets work for people, as opposed to having people work for markets?’

The answer is for markets to serve nature, rather than nature serving markets. Humanity needs to sync with nature, rather than seeing it as a force to be exploited. It is unlikely that our civilisation will survive unless we do this.

This is the central challenge facing humanity. In The Great Slowdown, James Scurry notes that the pandemic is an opportunity to face this:

‘We suffer because Nature itself, of which we are an inextricable part, deeply wants us to heal, both individually, as a species and as a planet.’

In a beautifully crafted essay, Sue Goss has suggested that we need to move from ‘machine mind’ to ‘garden mind’. While machine mind leads to human agency being treated as one cog in a machine to add financial value, garden mind sees human agency as a free and creative force attuned to natural processes of being and becoming to enable society to flourish and to sustain itself.

This kind of thinking inspired the birth of the Garden City Movement at the turn of the last century, but its lessons have been watered down amidst the takeover of town planning by property developers.

Practical suggestions

So, what are the practical steps to accomplish the changes needed? In this final section, I set out notes on this. In what follows, I will distinguish between the demand side of governance (namely, what people in civil society can do) and the supply side of governance (namely, what governments and official agencies can do).

In both cases, it is important to approach this task with humility because there are already many people, groups and organisations working in this space and it is important to get behind what is already happening rather than starting anything that competes with that. At the same time, more is needed because, while there is progress as green parties see their support grow, in many countries it is too slow. However, all is not yet lost. The Rapid Transition Alliance has shown that so long as there is speedy action, it is still possible to make the necessary changes. They cite many examples where politicians have moved quickly to accomplish huge tasks. These include building the railways in the 19th century, the New Deal in the 1930s, and preparation for the moon landing in the 1960s.

What these examples have in common is broad public support. However, such support is not big enough yet. As Colin Hines, who is widely credited as the originator of the Green New Deal, has pointed out:

Civil society has a big job to do to convince the public about the need for the changes. This involves developing a clear set of propositions about what green economics would look like. Stephen Pittam, Chair of Global Greengrants Fund, has done so. In the UK, he says a Social and Grand Green New Deal:

‘… would mean rejecting austerity and instead massively increasing employment in face-to-face caring and a countrywide green infrastructure programme. The latter would involve making the UK’s 30 million buildings super-energy-efficient, and tackling the housing crisis by building affordable, properly insulated new homes. Local public transport would be rebuilt, the road and rail systems properly maintained, and a major shift to electric vehicles instigated. A more sustainable localised food and agricultural system would be developed. This approach is labour-intensive, takes place in every locality, and consists of work that is difficult to automate.’

Civil society organisations can showcase examples of what this would look like in practice. To take one example, there has been a dramatic growth in community gardens and community-assisted agriculture across the world to meet hunger caused by the collapse of work following the pandemic. These and other examples show the power of local people to respond to the needs of local communities and show solidarity in working together to tackle collective problems. Bringing together these examples as part of a shared movement towards local growing would go a long way to reduce the transport costs and environmental damage associated with importing food. Evidence collected by the Global Fund for Community Foundations has found that such initiatives have had a profound effect on how local people see their agency and power to build assets, capacities and trust within their communities.

As well as showcasing what is already happening, groups in civil society can play a vital role in working together to campaign to persuade their governments of the need for change. This is a cause that almost every civil society organisation can support because everyone is affected by the issue.

Such a campaign could focus on something specific, such as setting aside government expenditure to support the transition. As an example, Stephen Pittam suggested how this might be paid for:

‘By an increase in government spending, fairer taxes and encouraging saving in what [Colin] Hines has described as “climate war bonds”. And in the event of a further looming economic crisis? A massive Green Quantitative Easing (GQE) programme.’

Such a GQE would replace the current programmes of quantitative easing that are designed merely to keep economies afloat. These tend to lead to inflated stock and property values for people who are already well off.

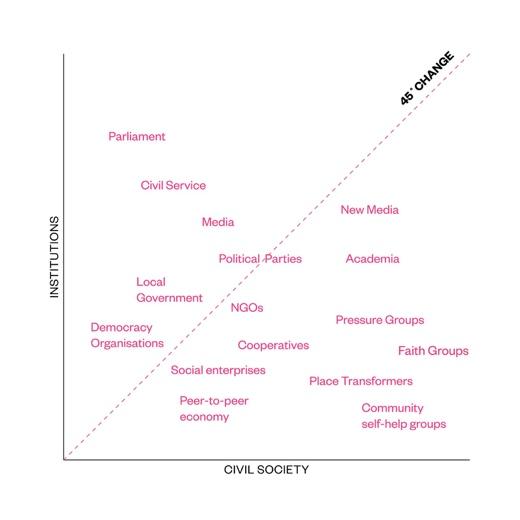

If we could work both from the bottom up and from the top down, we could use the methodology set out in Neal Lawson’s 45° Change: Transforming society from below and above. In using the processes of participative democracy that this entails, the approach could help to usher in a kinder society and one in which our politics supports people to continue to live on this planet and also to live well.

Such a perspective will bring civil society into direct conflict with the moneyed interests that control the economies of the world, though such conflict is a necessary and creative part of change.

Barry Knight is the author of Rethinking Poverty: What makes a good society?

Want to keep up-to-date with more articles like this? Sign up to our newsletter.

Posted on 13 Jan 2022 Categories: Blog, Climate crisis, New economic models, Community Wealth Building, Our vision, The business we want