Lessons from a citizens’ jury on climate change

Posted on 19 Jan 2022 Categories: Blog, Climate crisis, Cross-posts, Local initiatives, New democratic models, Citizens' Assemblies, Deliberative democracy

by Maria Lucien

With COP 26 starting in Glasgow on 31st October 2021, we have brought together the recommendations from six citizens’ juries and assemblies run by Shared Future over the last two years. A citizens’ jury amplifies the voice of local citizens and communicates their informed and considered recommendations for an effective and inclusive response to climate change.

Over the last few years, Shared Future has conducted six climate change citizens’ juries and assemblies in the UK. They are listed at the end of this article and linked in the text below.

A total of 174 people took part across all six processes. At the end of which each group of citizens came up with a coherent set of detailed recommendations – concrete proof of our belief that when given the information, space and support, citizens are perfectly able to navigate through even the most complex and intractable of problems. These recommendations not only provide a guide for local authorities and other stakeholders to base their policies and strategies on, they also show national government what support they must provide to nurture local action.

We sorted the recommendations from all six citizens’ processes into broad themes to find the top five most frequently mentioned climate policy asks. Helping governments and policy makers, nationally and locally understand what a citizen-led, low-carbon vision might be.

Our analysis shows that citizens place a lot of emphasis on greening transport, food and housing.

They also want more information available to make educated choices on consuming sustainably, as well as power devolved to local authorities to act decisively on climate change and to enact policies that can benefit their local area.

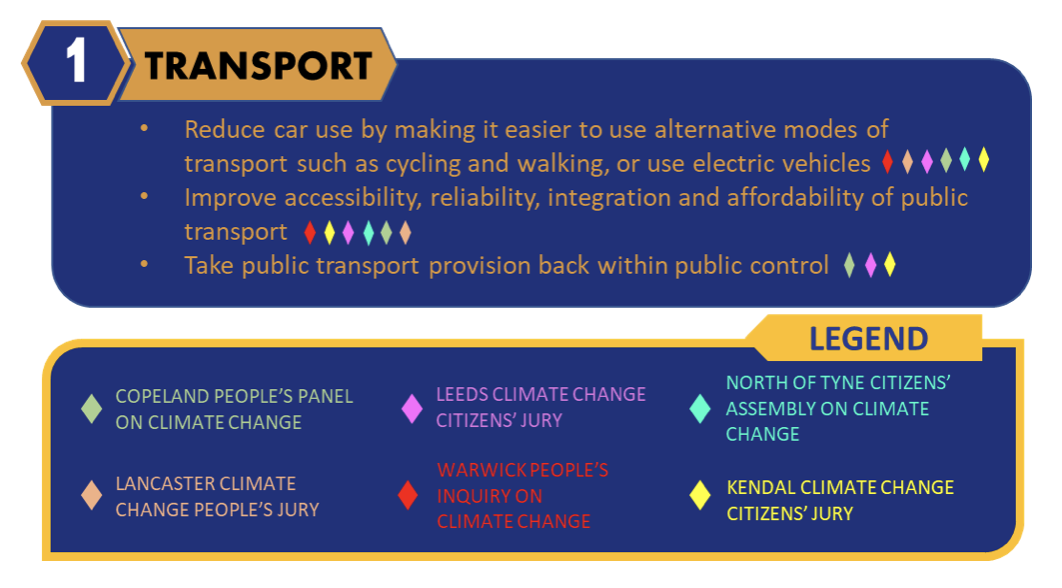

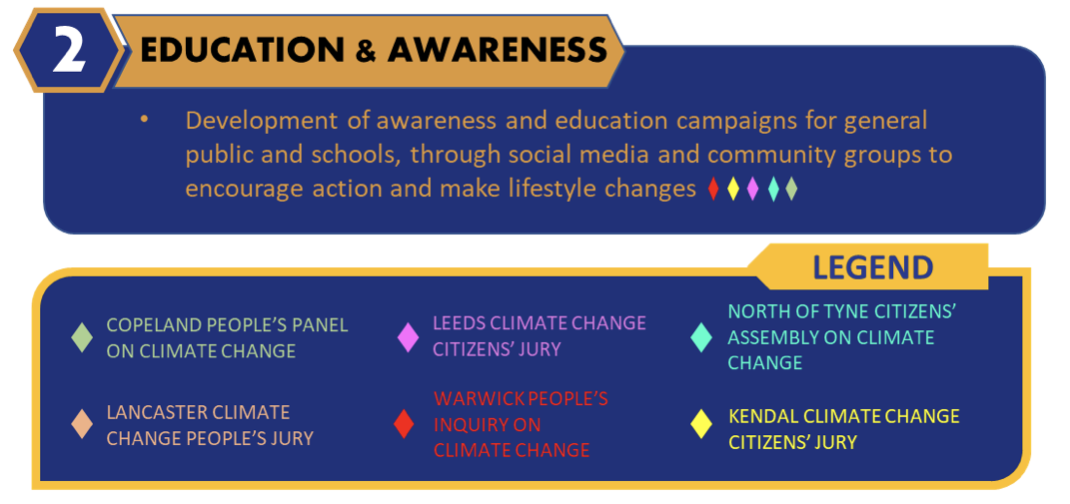

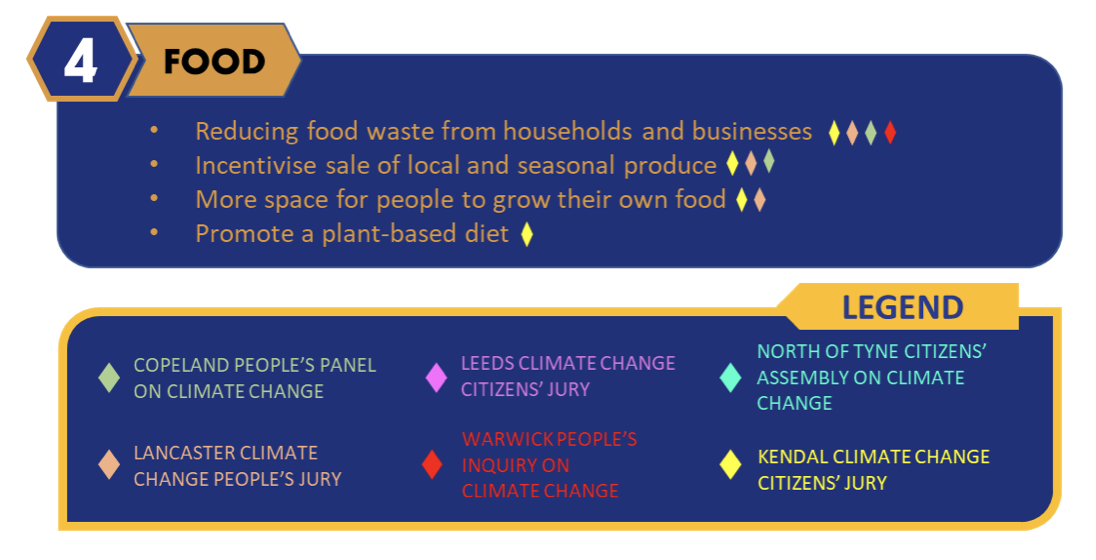

In the graphics below, the legend shows from where each of the recommendations emerged. We’ve placed the highest, based on the scoring used in each process, at the top. You can also download the infographic.

Transport

The most important theme emerging from the citizens’ recommendations, across the board, was transport. Proposals often reflected that the reduction of car use was highly dependent on the availability of alternatives that were equally viable. For example, Warwick’s top recommendation was to promote and encourage cycling by investing in better cycling infrastructure such as physically separated, better lit, quality cycle paths.

All processes suggested that public transport needed to be interconnected and integrated – for instance, Leeds called for a unified fare system similar to an Oyster card, while North of Tyne suggested integrated ticketing systems across entire public transport networks. Recommendations also emphasised the need for accessible, affordable and reliable public transport, to serve as a legitimate alternative to cars. Three of the processes also suggested bringing local public transport systems back under public control.

Housing

Making houses more energy efficient, and ensuring that new houses were carbon neutral and built to be more energy efficient was a priority for many of our citizens. It was the second equal combined recommendation overall.

All of the six processes advised retrofitting existing houses, buildings and council owned properties to increase their energy efficiency, as well as ensuring that new houses were built to meet energy efficiency standards, and constructed sustainably. Some also suggested that any new construction was carbon neutral. North of Tyne recommended that all new housing needed to achieve Passivhaus Standard and only be built on brownfield sites. Lancaster similarly suggested that while green belt development should be avoided, if it did happen any houses on the green belt needed to be built to Passivhaus Standard. Additionally, both Copeland and Kendal recommended setting up financial aid or grants for homeowners to retrofit their homes.

Education & Awareness

Spreading awareness and educating the public on climate change was a major theme of the recommendations across all processes, coming in joint second alongside housing.

Kendal suggested the development of a public engagement strategy in conjunction with the jury, local authorities and stakeholders to build a collective vision for the future. Leeds acknowledged the need for widespread, collaborative action, stating the need for a large-scale communication drive in Leeds to educate citizens on climate change. Lancaster also urged its City Council to invest in good quality messaging and marketing across a range of mediums to communicate information on reducing climate impacts and spread awareness of the climate emergency.

North of Tyne also encouraged the North of Tyne Combined Authority to invest in the development of a public education strategy, in a similar way to their effective COVID-19 awareness strategy. Copeland advised a series of Climate Change Challenges to be devised and promoted in schools, youth clubs and community groups to incentivise a low-carbon lifestyle. Warwick’s recommendations also asked for a collaborative communications campaign to encourage local climate action. This was an important thread in all of the processes – that education and the availability of information to citizens was a crucial step in promoting action on climate change.

Food

Food was another common theme. Warwick suggested that the council investigate measures for accessible community composting and food waste initiatives in neighbourhoods. Similarly, both Kendal and Lancaster suggested the need for tackling food waste, through food collections or the donation of surplus from local businesses. Copeland recommended encouraging supermarkets to sell local and seasonal produce, as well sharing information on carbon impacts of produce. This, they argued, would also have the benefit of educating people on the carbon impacts of their shopping and incentivise behaviour change.

Both Kendal and Copeland citizens stated the need for more farmer’s markets to encourage residents to buy local produce, thereby reducing carbon impacts from grocery shopping. Lancaster and Kendal suggested more space for people to grow their own food, not only to address climate impacts of food, but also to promote a sustainable, active lifestyle. Many of the food related recommendations were also built around encouraging citizens to build low impact food habits – Citizens in Kendal suggested the promotion of a plant-based diet.

Leadership

Most processes demanded better leadership in both local councils and national government in tackling the climate crisis. Leeds, for example, called for more locally devolved and decentralised power to allow for greater decision-making authority in the local area to tackle climate change. Kendal clearly stated the need for consistent and coordinated leadership from local authorities, calling for transparency on climate impacts of local policies.

Copeland also urged local authorities to form a plan that responds directly to their recommendations, with measurable targets in tackling climate change. This was echoed across most processes, with citizens directly calling on councils to respond to their recommendations and be open to be held accountable by both the public and members of these processes – all processes included recommendations that the participants continue to act as scrutiny groups of the implementation of their recommendations.

Furthermore, several processes called for local authorities to have climate change at the core of all decision-making and policy action in the area – in North of Tyne, for example, residents stated that local planning decisions needed to have climate change and the natural environment at their heart. Going further, that politicians needed to be lobbying national government for more local power. Lancaster echoed this, recommending that the council frame all of its work in the context of the climate emergency, without disruption from party politics. While Copeland also wanted local leaders to put climate change “at the heart and centre of everything that they do and say’.

A mandate for citizen-led policymaking

Citizens want action but that has to be done fairly. This means policies that not only benefit the environment, but also benefit their communities and local areas in aspects of transport, food and housing. Recommendations in these themes consistently call for viable, low-carbon alternatives, that allow citizens to transition to more sustainable, low impact lifestyles. They also want more information to be available and accessible to all citizens, in order to allow them to make educated consumer choices that can reduce their climate impact, as well as understand the scale and emergency of climate change.

Finally, citizens are clear that they require more decentralised power to local authorities to enable them to perform effectively, and enact policies that can benefit their local area. This leadership needs to be transparent, and held accountable by the people, while being inclusive and engaging the wider public in decision-making. And above all, this leadership also needs to place climate change at the forefront in its decision-making processes.

These recommendations crystallise the very real concerns that citizens have about climate change, and their call for urgent action. While this by no means serves as a comprehensive overview of the range of recommendations that have come out of these processes over the last two years, there are some clear messages about what citizens want from the government in tackling the climate crisis.

Despite the diversity in all of these groups, there was a unified response emerging that climate change is an emergency, and demands swift, radical action that is backed by consistent, transparent leadership. Leadership which at the same time recognises the added value for ordinary people that can arise from taking such action.

In the words of the Copeland People’s panel:

‘We have become hopeful of what could lie ahead’.

More information on the six sets of recommendations used to compile these findings:

- Leeds Climate Change Citizens’ Jury 2019

- The Kendal Climate Change Citizens’ Jury 2020

- The Lancaster District Climate Change People’s Jury 2020

- The District of Warwick People’s Inquiry on Climate Change 2020/21

- The North of Tyne Citizens’ Assembly on Climate Change 2021

- The Copeland Borough People’s Panel on Climate Change 2021

Click the infographic to download as a PDF

Maria Lucien is a project officer at Shared Future.

This was originally posted on the Shared Future blog on 29th October 2021.

Want to keep up-to-date with more articles like this? Sign up to our newsletter.

Posted on 19 Jan 2022 Categories: Blog, Climate crisis, Cross-posts, Local initiatives, New democratic models, Citizens' Assemblies, Deliberative democracy