Pandemic truths 6: How Covid-19 shone a spotlight on the warped values of our current way of life

Posted on 19 Aug 2020 Categories: Blog, Coronavirus, Local initiatives, The state we want

by Andrew Webster

‘Indeed, the one thing these prophecies had in common was that, ultimately, all were reassuring. Unfortunately, though, the plague was not.’

‘The truth is that nothing is less sensational than pestilence, and by reason of their very duration great misfortunes are monotonous.’

― Albert Camus, The Plague

This is the sixth and final piece in a series of articles in which Andrew Webster reflects on ‘12 tough truths’ that have always been known, but which have been thrown into sharp relief by the pandemic. This article considers food production and air quality. Click here to read others in the series.

Truth 11: Charismatic, ideological political leadership increases risks and ends up with poorer outcomes.

For anyone living in England it is an alarming paradox that the country that the World Health Organisation deemed in 2019 to be best prepared for a pandemic has suffered the worst excess deaths of any developed country in the actual pandemic in 2020. How did careful professional preparation fail to turn into effective public protection?

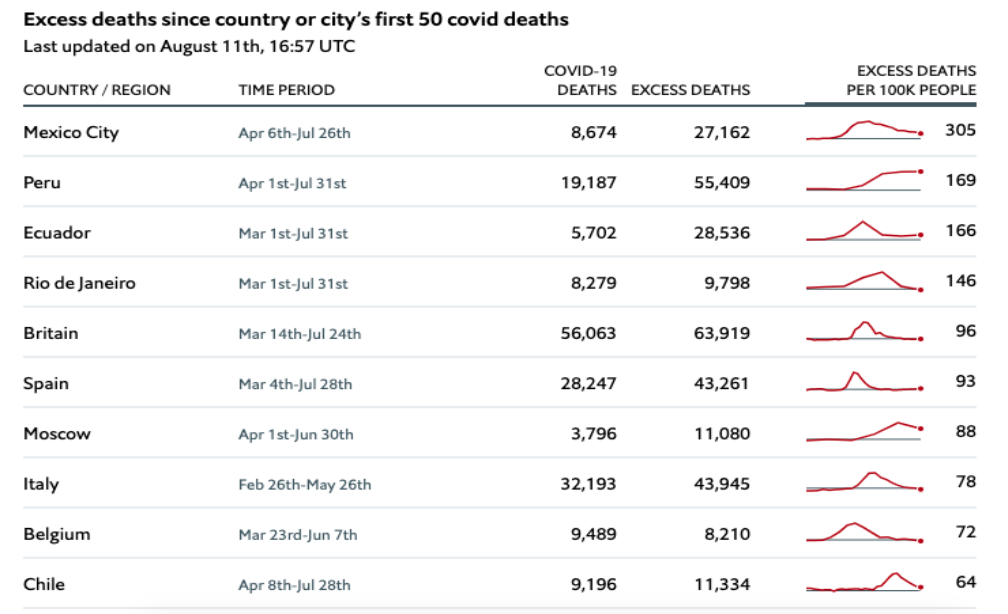

COVID-19 deaths are inconsistently counted across different countries. The best indicator of the pandemic’s impact is how many more deaths occurred from all causes than would normally have done in an average equivalent time over the past five years. In Britain that figure was 96 per 100,000 population – and local data shows that excess deaths were higher in England than elsewhere in the UK. Spain had a similar rate but look at the other end of the scale. In Germany there were only 11 excess deaths per 100,000 population, in Norway and Denmark the impact was negligible. Even the USA, widely regarded as disastrous by British commentators, only has a rate of 54 per 100,000. Clearly these are not yet the final figures so they are just indicators of impact so far.

I spent much of my career analysing, inspecting and trying to improve public services. If I could distil two clear lessons from this experience they would be: performance rarely correlates with commonly believed reasons for good performance. Well-funded services are often poor, and poor areas can have brilliant outcomes– and the difference is usually explained by the quality of leadership.

The Economist 11 August 2020

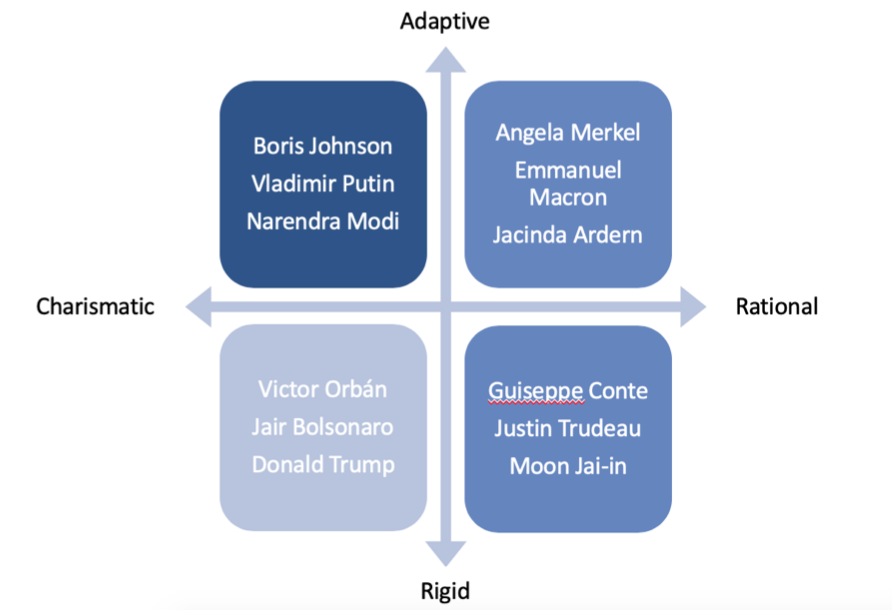

Michael Marmot has argued persuasively that ten years of austerity left Britain less healthy and more unequal and therefore especially vulnerable to the virus. I am sure that contributed, but other places in the table above are much less well-off and more unequal than Britain. Accordingly, I will concentrate on leadership and contrast the approaches taken in different countries. The old political fault lines I grew up with are not relevant to this discussion: communists and capitalists are as indistinguishable as Social and Christian democrats. I will use two evident dividing lines in current political ideology: should leaders adapt to a changing world (tackle climate change, manage migration, regulate technology) or should they bend the world to their will (deny climate change, control populations, exploit technology)? And should they lead charismatically or rationally? Leaders, therefore, operate on a continuum from rational to charismatic, from adaptive to rigid.

Not surprisingly, the rational adapters have done better. Equally unsurprisingly, this list contains the only two women among the 12 examples. These leaders were not better prepared than, say, Boris Johnson (most had impressive scientific advisers and health systems available to them) but they were ready to listen and challenge. They were, bluntly, scientific in their methods, rather than using science to mask political discomfort. Angela Merkel, of course, is a scientist. Scientific method is antithetical to charismatic leadership, relying as it does on doubt, challenge, being wrong, trying again when things don’t go as expected.

Once science had been used to determine an approach, there were some virtues in rigidity. At the early stage of the pandemic people were alarmed and uncertain, looking to government for clear rules to ensure safety and fairness. Again, charismatic leaders, accustomed to stoking resentment and riding on public anxiety, were ill equipped for the pandemic, as it would neither bend to their will nor be amenable to bland reassurance. George Monbiot has gone so far as to argue that the Johnson government deliberately ‘unprepared itself’ to avoid having to be consensual and rules driven in its leadership of the UK. Indeed, the delay in acting upon the warnings from elsewhere, the carelessness in so many becoming infected in face-to-face meetings in Whitehall, and then failure by key figures to follow the rules during lockdown all suggest a discomfort with a style of leadership based on consensus and clarity.

The Indian state of Kerala is a striking example of clear leadership. With a GDP per head only 5 per cent that of the UK, it has recorded only a handful of deaths from Covid-19. When Covid-19 was detected on 24 January, the state set up locally managed test, track, trace and isolate systems in three days. From 27 January all arrivals by plane were screened. A Communist Party of India-led state government has sustained land reform, education and public health services for decades. When asked the secret of her success, the state health minister KK Shailaja, a woman 63-year-old former teacher, replied ‘proper preparation’.

Clarity is in the hearing as well as the telling; it requires empathy with the viewer or listener more than elegant phrases or clever analogies. Jacinda Ardern explained a simple four-level response to the New Zealand public from her couch, with her family, taking questions over social media. While Boris Johnson regretted having to shut the pubs, Emanual Macron said sorry that the French government had got it wrong at first and promised to learn how to put things right. There is a clear contrast between political leaders who see government as a regrettable and expensive necessity and those who value solidarity between citizens and the state. In England, the government did not even give local councils access to data to assess risk and respond to infections for four months, whereas in Kerala they were winning that struggle in three days.

Leaders struggling to understand why confidence in them is slipping as the pandemic progresses would do well to look at another consulting and therapy staple – the change curve. Crudely put, while many of their populations are now in phase 2 – angry and depressed – charismatic leaders look badly stuck in shock and denial.

Truth 12: Social enterprises and charities make a disproportionate contribution to innovation and improvement.

Ipsos Mori polling suggests that the overwhelming majority of people in the UK do not want life after the pandemic to go back to how it was before. We want the opportunity to change the values and priorities that drive how we live, work, eat, travel and learn. Of course, we also want secure incomes, and homes and communities within which to flourish in a different future. How will we balance rights, responsibilities and risks as we try to shape an acceptable alternative?

Pulling together the threads that have emerged from the 11 tough truths articulated in this series of articles will enable us to conclude with a twelfth about how power and a disproportionate emphasis on accountability for risk have shackled innovation and community development.

To recap:

- Our health service focuses on hospitals, which are hazardous places for patients, staff and the public.

- We tolerate older and vulnerable people being poorly served by invisible care services that run on a shoestring.

- People’s income bears no relation to the value of the work they do.

- The welfare system is mean and cruel, but communities can be generous and kind.

- People’s need for human contact is too often served by work.

- Lots of educational content can be digitised but learning cannot.

- If you are poor and black you will live in poorer circumstances and suffer poorer outcomes.

- Every day violent men terrorise women and children and force them to flee their homes into public care.

- Industrial farming creates conditions conducive to new viruses that can transfer to human beings.

- Air pollution kills people every day and is mainly caused by unnecessary oil-powered travel.

- Charismatic, ideological political leadership increases risks and ends up with poorer outcomes.

For the last decade, since the financial crash, UK politics has been locked in a sterile argument about the role of the state. Should it be bigger or smaller? Should the government intervene or step back? Should major services be contracted from private businesses or run directly by the state? Can the circle be squared by clever regulation? The arm wrestle between corporate capitalism and state regulation has consigned us, as citizens, to being merely customers or voters. Our agency, generosity, energy, passion and talents find no outlet through public procurement or political activism.

Some of the 11 tough truths do need state action – to incentivise equality through taxation, to devolve leadership of health and welfare, to change the laws on older people’s rights, race equality and sexual violence. Others can be driven forward by responsible business practices – creating different workspaces and rethinking production and supply chains. But critically they nearly all require two deeper changes to our social culture.

The first is a different balance of rights and responsibilities, trusting citizens to make a contribution to the common good in return for a safe and supportive community where basic rights, security, income and health are guaranteed. This needs to be expressed as a commitment – not a deal, not an exchange, not a transaction – but something more binding and lifelong. The closest to this I have experienced is the pride felt by asylum seekers on achieving UK citizenship.

The second is a fundamental rebalancing of risk. Social enterprise, charitable endeavour and community action are hidebound by state bureaucracy that prefers large corporate suppliers or state control, and a regulatory regime that bakes in audits and standards for those purposes. To bid for a public contract requires an indemnity beyond the means of a small community group. To receive a grant or a loan requires guarantees that deter many. Charitable law ties up talent, resources and time in managing often sclerotic committees when energetic innovation is what is required. Councils constrain social enterprises’ ability to invest by demanding they meet legacy liabilities – for example asset depreciation or pension fund costs. Yet, councils, working with businesses and banks, could use their pension funds and asset bases to invest in a better future – taking equity stakes in new enterprises and community initiatives that grow healthy food, create sustainable housing, provide pollution-free travel, generate solar energy, run outdoor schools, research new health treatments, support mental well-being, and host rational, adaptive dialogue about how to confront challenges and problems.

So, the twelfth tough truth is that social enterprises and charities already make a disproportionate contribution to innovation and change, but that if we truly want to #BuildBackBetter, we must trust them to lead the way we live.

Andrew Webster is a Trustee of Centris and an advisor to health and care systems and businesses, having worked in the NHS, Local Government and Central Government for 35 years.

Want to keep up-to-date with our coronavirus coverage? Sign up to our newsletter.

Posted on 19 Aug 2020 Categories: Blog, Coronavirus, Local initiatives, The state we want