Citizens Assemblies: fashionable focus groups or the great hopes of democracy?

Posted on 03 Aug 2021 Categories: Blog, Local initiatives, New democratic models, Citizens' Assemblies, Deliberative democracy, The place we want

by Katy Oglethorpe

Newham citizens assembly

Newham, the East London borough: home to the 2012 Olympics, birthplace of Danny Dyer and the most ethnically diverse place in England and Wales. Soon Newham will add another string to its bow, hosting the first permanent citizens assembly in the UK. From September, a randomly selected group of residents will come together to advise the council on some of the most important issues of the day.

The first topic for the citizens assembly has not yet been selected – appropriately it is up to Newham residents to choose between topics that include health inequalities, a ‘new deal’ for young people, and seizing the potential of technology.

After Newham residents have come up with recommendations on one topic the group will continue indefinitely refreshing the citizens assembly members so nobody serves twice.

“We want the assembly to have a real legacy. Ultimately it should just be part of the furniture, just part of way the council does business,” says Jessica Crowe, Newham’s Corporate Director leading the initiative.

Newham still has one of the highest deprivation rates in England, despite the economic growth spun out of the Olympics, says Crowe.

“The lives of too many residents of Newham are insecure, both economically and socially, and can leave them feeling powerless,” she says. “We want to show people: your council is listening; it’s giving opportunities to influence what’s happening around you. And that sense of agency and purpose can affect all sort of things – including wellbeing and happiness.”

Newham may be planning the first standing citizens assembly, but it is far from the first council or government to grasp the promise of this big, shiny style of deliberation.

“We are living through the biggest number of citizens assemblies I’ve seen in my life,” says Rich Wilson, leader of hundreds of public deliberations.

Citizens assemblies are going on in a whole range of places, tackling a whole range of issues. They’ve been national – on the future of social care; or on climate change assemblies in Scotland. There have been regional exercises on how Bristol can recover from Covid-19; whether assisted dying should be allowed in Jersey; how to help people have a healthier relationship with alcohol in the Wirral. And there have been hyper-local initiatives –like Test Valley’s assembly on the regeneration of the area around a local bus station.

These public deliberations are seen as a way to untangle some of the knottiest and most divisive issues we face, building knowledge, empathy and passion among the public and to ultimately hand policy makers fresh – and pre-endorsed – ideas.

But are citizens assemblies worth the significant time, money and effort spent to hold them? Do they really amount to more than a fashionable focus groups? And will they really have an influence on the political limitations of our centralised country?

The ingredients of a citizens assembly

What makes citizens assemblies different from traditional consultations – and their outcomes more interesting, is that participants aren’t selected on the basis of who is most keen to share their views. Great pains are taken to move beyond the ‘usual suspects’ who voluntarily attend council meetings and achieve a mix of participants on race, age, occupation, type of housing, political stance, and other factors.

“You really want people who come to be representative of the community, not representative of the type of people who come to local meetings,” says Will Jennings, pollster and expert on citizens assembly selection.

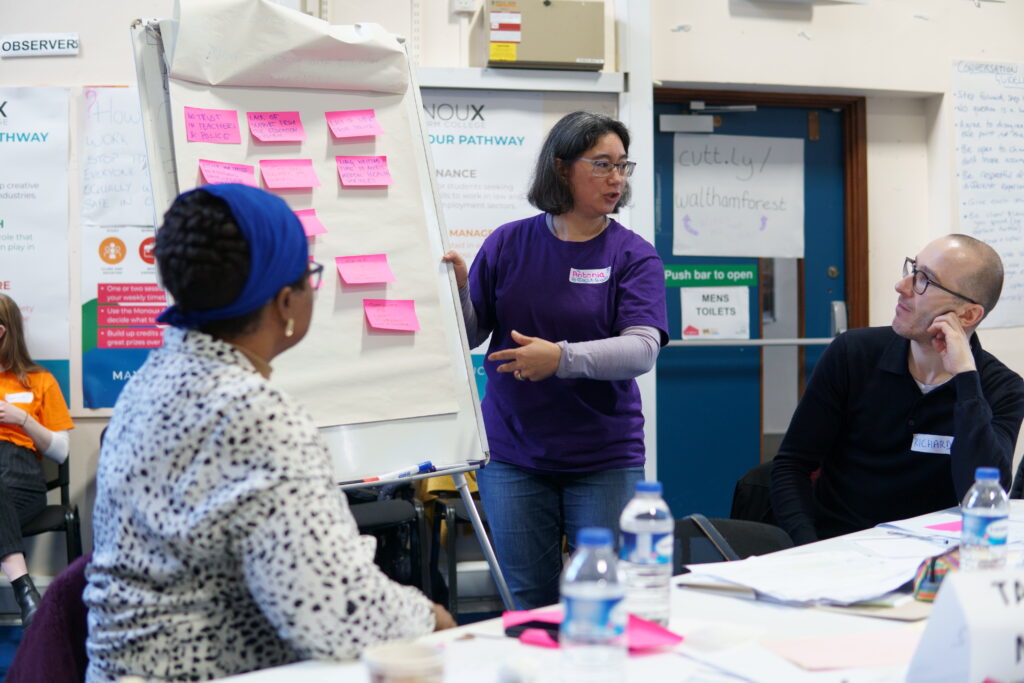

Assemblies typically take place over days or weeks. Participants don’t go straight into debating an issue; they build expertise first with the help of experts and people with first-hand experience. In Waltham Forest’s assembly on hate crime for example, participants heard over 20 guest speakers, including the director of the Antisemitism Policy Trust, Tower Hamlet’s lead on anti-female violence, and a police superintendent, who was also a member of the Muslim community.

Because of the level of detail, citizens assemblies are particularly suited to ‘wicked issues’, says Jennings, the policy dilemmas that can’t be explained in a slogan or leaflet, where politicians are often genuinely at a loss as to how to tackle them, and need the public onside.

“The most fruitful topics are ones where people would normally go for quick-term fixes, or conflicts where we all know that something needs to be done but we choose to kick the can down the road,” says Jennings. “These are good spaces to explore and force people out of their comfort zone.”

Radical outcomes?

The most famous – and celebrated – examples of citizens assemblies probably come from Ireland, where two groups recommended legalising gay marriage and then abortion, prompting law changes for both.

There is other evidence that assemblies can help people reach a consensus on polarising issues. And that this consensus tends to transcend the political status quo. A small US study of deliberative polling (a close cousin to citizens assemblies) found respondents tended to move toward more “cosmopolitan, egalitarian, and collectivist value orientations” by the end of their experience.

In deliberations organised by UK in a Changing Europe and National Centre for Social Research participants became more likely to say immigration was ‘good for Britain’s economy and culture’ after taking part. Meanwhile, the assembly on Brexit recommended a soft exit from the EU and another suggested over-40s get taxed for social care.

In Test Valley district in Hampshire, residents were asked to advise on developing the area around a town’s bus station. James Moody, head of strategy and innovation at the district council, says previous resident engagement tended to be reduced to conversations about parking and the use of the community hall. In the assembly however, participants came up with unexpected suggestions.

“They amplified different things than we expected them to,” he says. “They put green spaces, wellbeing and the public realm at the front and centre of any future changes for the area. Suddenly all the things we dreamed of doing, we had a mandate.”

This was eye-opening for elected members too, who took part as expert witnesses and observers. For Moody, this “democratic link” was key, as participants learnt about the ‘give and take’ of policy decisions, and politicians leave with a clear mandate, a sense of involvement and heightened appreciation of their community’s insights and ideas. Basically, both sides build empathy.

It might be this empathy that helps yield new approaches. In a citizen’s assembly, if done well, people are searching for solutions, seeking the common-ground, listening to each other and building understanding as a key part of the process. But is harmony really guaranteed in a country we’re constantly told is divided?

“We had a very long risk register going into it,” says Laura Butterworth, who helped set up Waltham Forest’s hate crime assembly. “We were aware that many of the participants would have very different political views. There was a huge potential for people to get into fights, and for the discussions to trigger emotional issues.”

The council provided a wellbeing room with a counsellor on-hand. But ultimately it was hardly used, says Laura. “Despite being from very different walks of life the participants were respectful of each other, and the discussions were harmonious and meaningful,” she says.

Turning views into action

Given this evidence, Jessica Crowe of Newham is hoping that the area’s citizens assembly not only improves decision-making but also wellbeing. It’s clear that those who take part in citizens assemblies get a lot from the experience. Diaries written by participants in the Scottish Citizens Assembly consistently show early cynicism turning to surprise, delight and ultimately fervour for the process. They speak of a huge sense of pride at being invited and a feeling of being part of history.

“It’s a huge honour to be part of shaping the future of the country you live in,” writes one participant, a woman in her 70s or 80s. “I won’t be in it for a long number of years but if I can contribute anything I want to contribute a good place for my grandchildren to grow up.”

Councils like Waltham Forest and Cambridge can point to glowing endorsements of individuals’ enjoyment, and of the effect on trust, confidence, and connections.

Even more telling is the number of times ‘more citizens assemblies’ are a key recommendation emerging from citizens assemblies themselves. This is the case in the Climate Assembly of Scotland, where a top recommendation was to make further use of the method, including involving citizens in reviewing existing legislation.

But are these grand ambitions and high hopes always realised? What happens to these diligently crafted consensual decisions after councillors and politicians return to their day jobs?

The cynical answer is: sometimes not much. After all, we have no over-40s social care tax yet, and our Brexit deal was more al dente than soft. Even in Ireland, as Naomi O’Leary points out in a piece called The Myth of the Citizens Assembly, most of the groups’ recommendations never saw the light of day.

“There is a danger that deliberation can raise expectations about what’s possible on certain issues to levels that can never be fulfilled,” says New Local Senior Researcher Luca Tiratelli. “This carries a big risk of alienation among people and a loss of credibility on behalf of the convening body.”

This is proving a painful lesson for Macron in France, who promised to put forward nearly all the recommendations from the Convention citoyenne pour le climat, “without filter”. Instead, only half of the proposals have made it into a climate bill, something that left one participant feeling “bitter and upset”. “The government said they wanted us to deliver solutions but then they just picked what they wanted,” he told Deutsche Welle.

But at a local level there’s often a smoother route from citizen to policy. A report from UCL’s Constitution Unit found that out of 13 local citizens assemblies in the last 18 months, nine councils had taken ‘significant steps’ towards implementing the recommendations. It’s a good proportion, given that the 18 months also contained a global pandemic.

Romsey, Waltham Forest and the Wirral are all enacting their citizens’ recommendations. Last year, Camden became the first council in the UK to commit to policy change based on the climate emergency action plan put forward by its assembly, including making all new buildings carbon neutral and increasing the number of segregated cycle lanes, with Leader Georgia Gould telling LGC that they were the “future of democracy”.

Fancy, eye-catching and costly

Citizens assemblies are the “fanciest and most eye-catching” way of doing engagement, says New Local’s Luca Tiratelli. But are they necessarily the best? Some councils are now treating assemblies as a de facto approach, he says, when other, smaller types of engagement might better meet their goals. “When we look at the boom of assemblies on climate, it’s almost like step one is declare an emergency; step two is hold a citizens assembly. But what’s after that?”

And citizens assemblies are expensive . To recruit 120 people for Scotland’s meeting, the teams organising it knocked on some 10,000 doors across the country. Each participant was paid £200 for every weekend they attended, the assembly’s total cost was £1.4m.

Councils are also using cheaper, less publicised methods to grow community power and find out what their residents think. Panels, community researchers, community engagement officers, one-to-one community engagement.

Citizens assemblies work best when there is genuine issue to be solved or as a way to mobilise communities around an important topic, says Tiratelli. Using assemblies to add fuel to a cause isn’t something to be shy of, he notes. “With a collective emergency like climate change – you not only want people to think; you need them to feel part of delivering a solution, and then help deliver it.”

Political barriers

For some, the potential of citizens assemblies won’t be met until our democratic system shifts to make room for community power.

Adam Lent, New Local’s Chief Executive, says: “People in power need to commit to enacting recommendations from citizens assemblies. This is the only way they’ll become something with teeth, that people and policy makers take seriously.”

There are overseas examples of assemblies reaching the bloodstream of the body politic.

In Gdansk, Poland, assemblies have powers to direct policy and funds, and citizens can collect signatures to initiate a deliberative process.

In Taiwan, the government has created an online deliberation platform that fosters discussions – aiming to find common ground between diverse opinions rather than just the majority-held view. It’s already been used to agree permissions relating to Uber and the use of e-scooters.

And in German-speaking Belgium, the federal government have set up a new permanent citizens forum where people can put forward recommendations and monitor their progress through parliament.

Soon, Newham will join the list of places turning a citizens assembly into something permanent. Meanwhile there are new assemblies planned in countless more cities, towns and districts, as more and more councils recognise their potential. Perhaps participation could one day be like jury service, suggests Will Jennings, part of our routine democratic obligations and expectations.

Citizens assemblies are only one example of the huge array of ways governments – particularly local governments – can and are turning to citizens to help them answer real, important issues. In an era where low trust in government and a dearth of control can easily explode into the Gilets Jaunes riots, the division over Brexit, or the election of a populist president, there is a place for collective, measured and empathetic decision making. While polls, surveys and even elections give us a momentary snapshot of people’s unvarnished opinions – citizens assemblies and their deliberative cousins offer something deeper and more long-term, driven by the consensus that eludes our political discourse.

“I think we are living through the third great democratic struggle – the right to influence policy,” says Rich Wilson. “I think in 10 years we’ll see politicians widely delegate power. At least – it will be a choice between this or becoming totally authoritarian. Citizens assemblies show there’s a real demand for democracy. We need to be prepared to meet it.”

This was originally posted on the New Local blog on 11th May 2021.

Want to keep up-to-date with more articles like this? Sign up to our newsletter.

Posted on 03 Aug 2021 Categories: Blog, Local initiatives, New democratic models, Citizens' Assemblies, Deliberative democracy, The place we want