A stitch in time saves nine: Learning from Blackpool

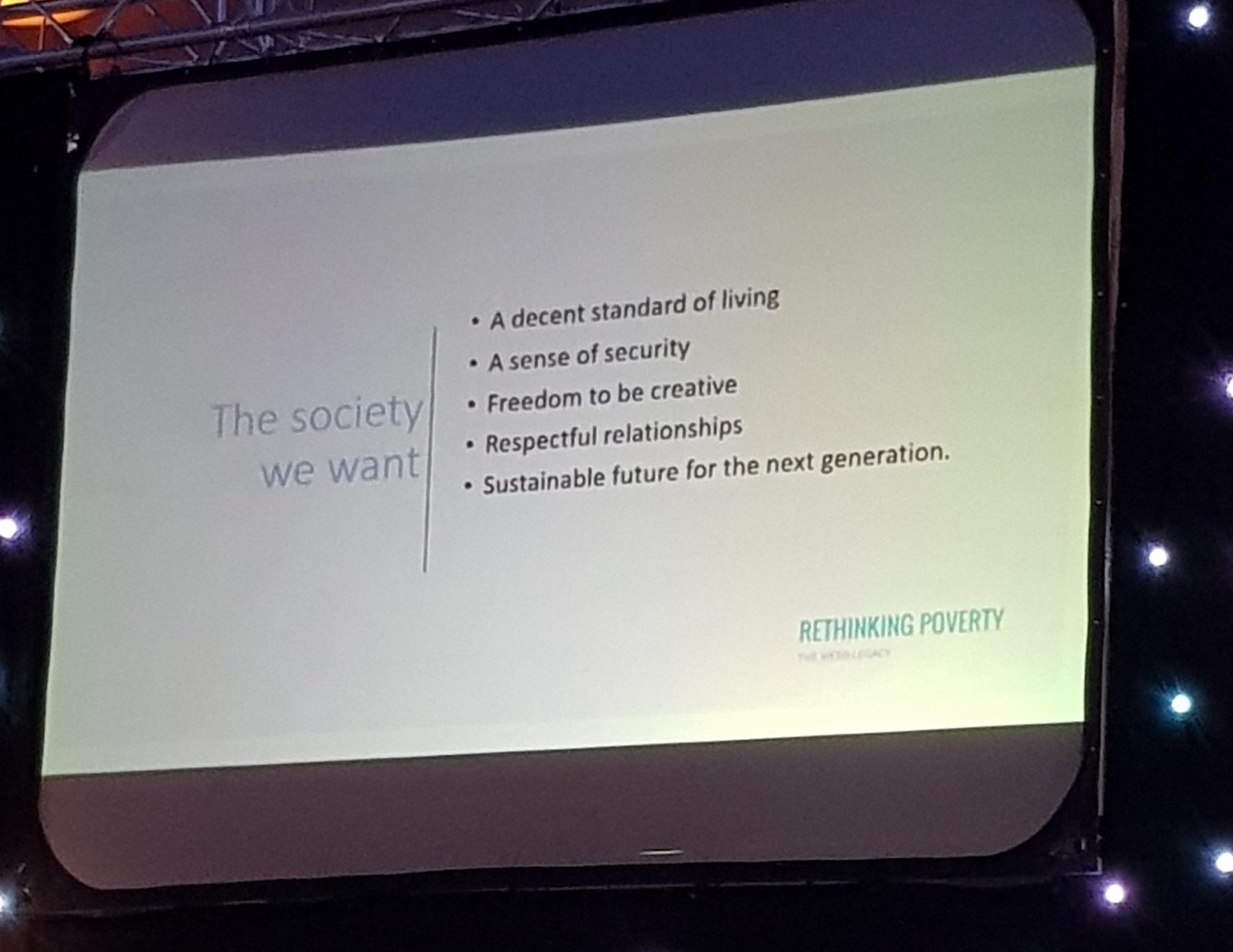

Posted on 27 Nov 2019 Categories: Blog, The place we want, The society we want

by Barry Knight

Important lessons emerged from a one-day conference ‘Transforming Blackpool together: how evidence is changing our town’, held at the Blackpool Winter Gardens on 14 November.

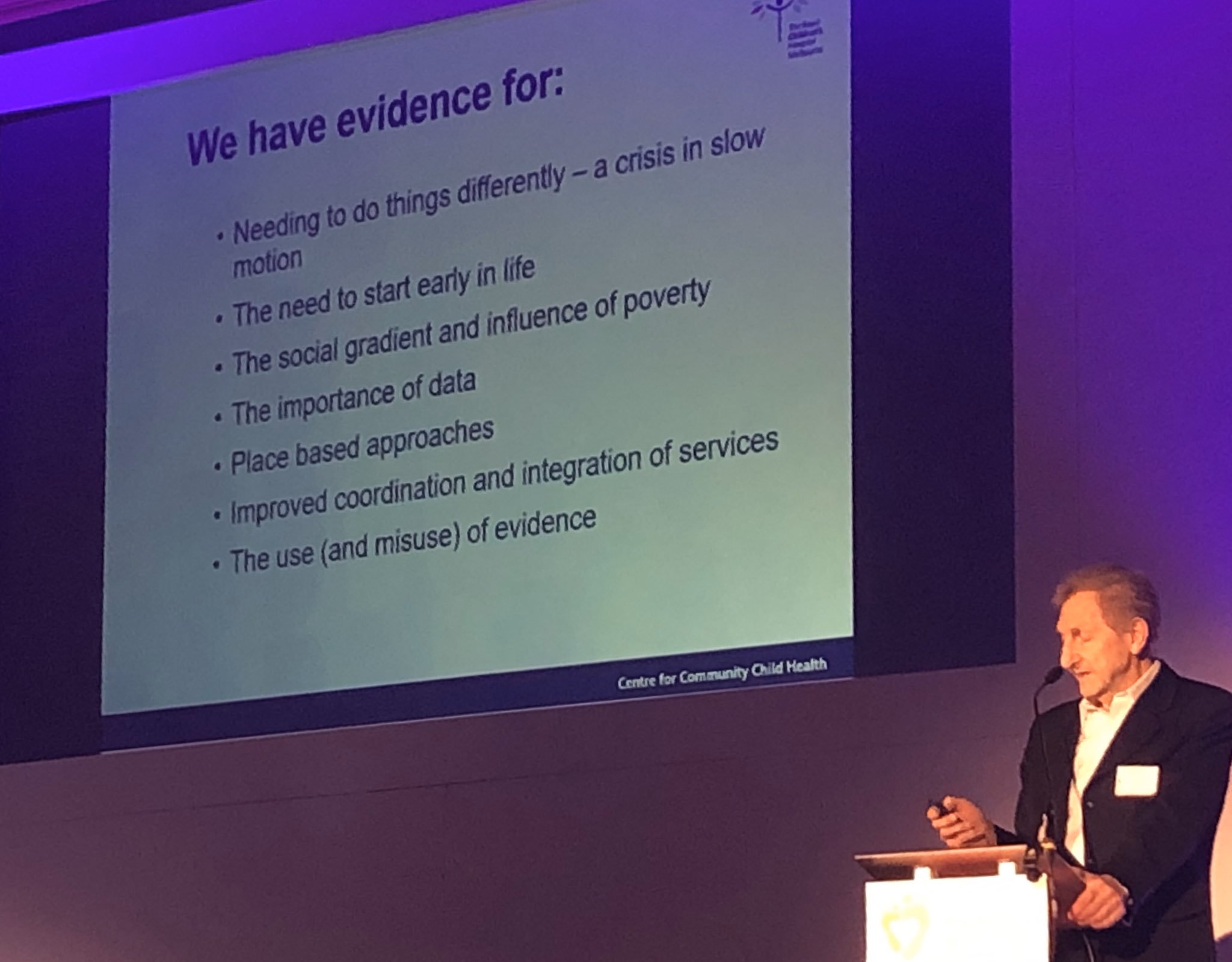

Frank Oberklaid, a paediatrician from Australia, told an audience of 300 people that outcomes for children are getting worse across the world. This is the first generation when children are not expected to do as well as their parents. Even in an advanced economy like Australia, as many as one in five children go to school hungry.

Problems start early. In babies, poverty and its attendant stress affect the architecture of the brain and the body. Children in poverty are subject to an inverse care law in which those most in need are less likely to get attention than their richer peers. The longer problems go untreated, the more the efficacy of intervention goes down and the cost goes up.

Governments fail to see this. They typically wait until the problem is entrenched and throw money at it at the point of crisis. By then it is too late to get at the roots of the problem, and efforts usually fail because they are single silver-bullet solutions directed at symptoms.

We should, in any case, question the wisdom of silver-bullet solutions. Even if grounded in evidence of ‘what works’, they don’t necessarily transfer well from the context in which the study was conducted. The fidelity of the programme is often violated because the assumptions of the model of intervention are not fully met. Governments applying formulaic top-down interventions have a poor record of achievement. As Oberklaid put it, ‘the only thing you make from the top down is holes.’

Interventions need to be complex. They must be place-based, related to the whole family rather than a single individual, rooted in community structures, and involve a one-stop shop for social and health services. Having lots of different organisations pursuing their own service independently of each other is deeply confusing for people seeking help. ‘There must be no wrong doors,’ says Oberklaid. If people are seeking help, they must find it at their first point of entry.

Data on interventions must be shared with the community, says Oberklaid, because they have many of the solutions. There is a case for ‘broadband funding’ that involves writing the community a cheque so that they can set the outcomes. Once this is done, the funder can hold the community to account for achieving the outcomes. Managing inputs is never a good idea, and we must trust communities if we are to make progress.

At the conference, I ran two sessions on ‘the town we want’. It was clear from the 160 people who attended that people from Blackpool’s communities are keen to be involved in developing the town. Rather than just being consulted about programmes, they wish to engage fully and become leaders in the quest for social advance. Blackpool’s Better Start Programme is an opportunity to make such community involvement authentic.

Neil Jack, chief executive of the town council, sees such community involvement as the key to success. As a town that has lost £800 million in cuts since 2010, he says that there is ‘no external rescue coming’. Solutions have to be found from within the town.

As we head into an election with both of the main political parties saying the days of austerity are behind us and committing themselves to raising public expenditure, we need to heed a warning given by Paul Johnson of the Institute of Fiscal Studies. He says: ‘It’s not a question of splashing the cash so much as what lies behind it.’

How the money is spent matters, and both of the two main political parties are developing policies that keep the power in Whitehall. What is needed for places like Blackpool is decentralisation so that local people can figure out their own solutions. We need properly funded local government and a central government that has an enabling rather than a controlling role.

Unless power is given to local actors, there will be little prospect of addressing the despair and disconnection that runs through Britain’s poorer places. Undoing the damage done by 10 years of austerity will take time to mend. The first stitch is to trust local people to do the job and to give them the resources to do it.

Want to keep up-to-date with more articles like this? Sign up to our newsletter.

Posted on 27 Nov 2019 Categories: Blog, The place we want, The society we want