Creating a new narrative for a good society – lessons from Letchworth

Posted on 26 Sep 2018 Categories: Blog, From Rethinking Poverty, Good Society, Housing, New economic models, Our vision, The business we want, The place we want, The society we want, The state we want

by Rethinking Poverty, Compass, TCPA, University of Hull, UCL

What would a good society look like and how can we achieve it? As described in yesterday’s blog, a small group of people got together in Letchworth Garden City on 26 and 27 July to attempt to find answers to these questions.

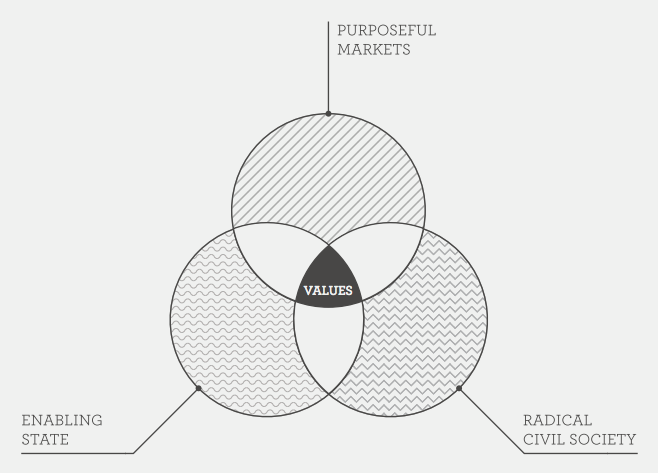

There are three key elements in any vision for a good society, it was suggested. First and foremost is what we decided to call ‘radical civil society’ – spaces for reimagining, for purposeful construction. Then there are markets: can they be socialised rather than aiming solely for profit? Can they have values? Finally, the vision must include a good state: what is the role of a good state in relation to everything that is bubbling up from below?

The next question will be: how do these elements of civil society, market and government come together in specific places? And how does the local relate to the national? Clearly not everything can be solved at local level. Climate change, for example, is going to demand a big-state – indeed, a global – answer.

Radical civil society

There’s currently a great deal of energy going into seeking a new future, and much of what’s happening is collaborative and participatory. People are creating alternative, sustainable, local economies. Some have built enterprises to support them. People are doing a lot of things without money – digital currencies, mutual aid, time banks. The good help movement is another sort of initiative, an emerging community within public services whose aim is to reform public services by offering people help in a different way, starting from what people themselves want. Alternative campaigns and protest movements like the campaign against fracking are flourishing – though they are often single-issue and may end when the goal is achieved.

Does this kind of radical civil society exist everywhere? A study of York has identified a thousand different groups doing things there, which suggests there might be a lot more than we know about going on everywhere.

Where it really is absent, what can be done? Carnegie UK research has looked at how radical civil society emerges and concluded that you can’t facilitate this. Often a strong cause like that of the suffragettes with a clear end goal can fire people up to take risk. In South Africa civil society was most radical when most oppressed. The #ShiftThePower hashtag has been successful because people in southern civil society feel oppressed by northern aid and have responded to it emotionally.

There are all these different visions but they are molecular, fragmented, isolated. How do we bring them all together? In the 19th century mutuals and co-ops were created and came together in a movement. Are today’s populist and environmental challenges sufficient to call forth a similar movement now? It might be easier to bring people together around themes rather than places, it was suggested. At Toynbee Hall in East London efforts to bring together financial services ‘disruptors’ did work, and community-based food initiatives like Incredible Edible have been successful in bringing people together.

There is a tension between two approaches to providing the glue to bring all the different initiatives together: expand from below, engaging with people on their own terms; and educate from above – not as an elite activity but by developing a vision, eg #ShiftThePower. Sometimes someone needs to take a leadership role.

Values-based markets

Can we reshape capitalism? Things are already happening here. There is a powerful movement within capitalism to become more socialised. Narratives are emerging from different political perspectives about how capitalism can be made to work to tackle inequality, climate change, etc. Blended value, triple bottom line, B Corps, social impact investment and the whole social enterprise movement are examples. There is a viable cooperative model, here and internationally, and the co-op movement owns a lot of land. Unilever provides an example of a big company that is making huge strides, having recognised there is no sustainability for it in a world threatened by climate change.

These examples show that we shouldn’t see markets/trade/exchange as synonymous with destructive capitalism. Markets do have the potential to create significant good. Time banks, for example, are about how you make markets work for people. So reshaping capitalism isn’t anti-capitalist or anti-enterprise; it could appeal to people who are more on the right.

The question is: can this movement be expanded? One approach to doing this is to place restrictions on what capital can do – but businesses are very good at evading regulations. Another is to create enabling measures – but they tend to work only at tiny scale. Perhaps funds could be created that can be invested only in certain new businesses, eg those that are developing a distinctive character for the local economy, or a more diverse high street?

“Markets do have the potential to create good”

At present we have some big companies reforming at the margins, but there is no alternative at scale. Where there is more scale, as in Germany and Ireland, the state has played a very instrumental role, eg in terms of facilitating regional banking. We’re not just talking about new control mechanisms; we need innovations, a new mix. We need a new alliance between radical civil society and the good state in order to dominate the debate and be more powerful than capitalism.

How do we get government to take action? The state has been very active in terms of regulating financial services in order to benefit consumers so we know it can be done. The biggest hope for changing the system may be around specific industries like housing where millions are suffering real harm from a dysfunctional housing system driven by big housebuilders led by profit who build by volume rather than building a good product. Here the desire for change could create a groundswell to stimulate government action. But first we need to convince people that there is an alternative.

While we need to be realistic about how powerful the wealthy/businesses are and how much they will resist anything that threatens their position, we also need to remind ourselves that capitalism can be reformed and campaigners can have an influence on people. We need to claim the moral high ground. Our overall message: in the long run big capital isn’t part of the future that we want, but we’re OK to go along with it for the time being as it reforms.

A good state

Finally , we need an expanded, socialised, sensitive state. The state must have an enabling and a guaranteeing role, enabling and supporting change to happen, and guaranteeing a level below which no one/nowhere should sink. Both enabling and guaranteeing are roles for local government, with central government the final guarantor.

For this to work, the relationships between local and national governments need to be clearer. Local governments often aren’t clear what they are allowed to do. For example, can they develop/distribute/sell energy, as they can in some European countries? The fundamental problem with the state in the UK is that it’s overcentralized. The enabling state must operate at a local level.

“We need… local actors ready to pull power away from the centre’”

The trouble is that the central state won’t readily give up power; increasing centralization has occurred under successive governments. At the same time a decade of austerity has sucked the energy out of local government. Too often the sole aim now is to run the council as efficiently as possible. The desire to do things differently has gone. What we need, in one view, is ‘confident local actors ready to pull power away from the centre’. Andy Burnham in Manchester, for example, is tackling housing without waiting for permission.

Other examples of councils doing things differently include Frome in Somerset, where Independents for Frome have run the town council since 2015, when they blew away all other parties; and Barking & Dagenham, where the local authority under Darren Rodwell is regenerating the borough through companies created and wholly owned by the council. The aim is to do this in a way that will benefit local people through the development of skills and training. In Preston the local authority has made a decision to build the local economy by employing local companies to deliver services for the council rather than outsourcing to bigger companies that take the money out of the area.

All too often the state tries to be efficient and ends up cruel; can we build a state that is both efficient and kind? As one participant put it, can the state love?

Andrew Webster, KPMG

Barry Knight, Rethinking Poverty

Caroline Hartnell, Rethinking Poverty

Frances Foley, Compass

Gill Hughes, University of Hull

Hugh Ellis, Town and Country Planning Association

Jonny Mallinson, London Borough of Barking and Dagenham (seconded from the Innovation Unit)

Kate Henderson, Town and Country Planning Association

Ken Spours, UCL Institute of Education

Neal Lawson, Compass

Read the first in this series ‘What could planning contribute to achieving a good society?’

Posted on 26 Sep 2018 Categories: Blog, From Rethinking Poverty, Good Society, Housing, New economic models, Our vision, The business we want, The place we want, The society we want, The state we want