Five things you may not know about Beatrice Webb…

Posted on 21 Sep 2017 Categories: About Beatrice

Remarkably few people have heard of Beatrice Webb and her husband Sidney. When we ask the question. it is usually just a handful of academics or politicians who know who she is. Yet she was widely recognised in the first half of the 20th century and described on her death by Maynard Keynes as ‘the greatest woman of the generation now passing’.

She had a real focus on the vital need to alleviate and reduce the causes of poverty. She learned about the conditions of the poor by working amongst them – no ivory tower for her, As a committed Fabian, she brought her research skills to the challenge; setting out the evidence, looking for causes and solutions, developing workable policies and agitating for change.

So here in a nutshell are 5 things that you may or may not know about Beatrice Webb.

1. She was part of a unique partnership with Sidney

She and Sidney met through the Fabian Society. Together with Bernard Shaw, they had been prominent Fabians, Sidney writing ‘Facts for Socialists’, the first Fabian tract and Beatrice a paper on ‘The Cooperative Movement’, then of particular interest to women. According to Shaw, Beatrice sampled the Fabians as possible husbands by inviting them to Gloucester for successive weekends. Shaw refused to go as his friend Sidney was infatuated with her and he didn’t want to get in the way.

Beatrice was attracted to Sidney’s mind and they married in 1892, spending their honeymoon carrying out research. Beatrice’s money enabling Sidney to leave the Civil Service and go into politics, being elected to the London County Council in the same year and much later in 1922 as a Labour MP. At the time, women could not sit in Parliament or on local councils – or, of course, even have a vote.

It was an extraordinarily close partnership and they were prolific researchers, writers and campaigners. Beatrice had a wide political knowledge and influence and came up with more of the ideas and architecture, while Sidney had a talent for drafting and committee work. But their work was rigorously analytical and any differences that they had were always thrashed out based on research evidence. John Stuart Mill wrote: “the writings which result are the joint product of both and it must often be impossible to disentangle their respective parts….”.

They were always keen to learn and debate new ideas and Beatrice became renowned for inviting prominent people to evenings at their house (or salon) for lively discussions. In these early days, particularly, they believed in ‘permeation’ – influencing people of all political persuasions to their ideas and ways of thinking.

2. They founded the London School of Economics

In 1894, a Henry Hutchinson committed suicide, leaving a will with a bequest of £10,000 towards advancing the objects of socialism and creating a Trust, with Sidney Webb as chairman. The Webbs, together with Bernard Shaw, decided that part of the money should be used to fund a school in London on the lines of the Ecole Libre des Sciences Politique in Paris. Their idea was that students should be free to study social conditions in a scientific way, pursuing the truth independent from any dogma. But how did this square with promoting socialism? Sidney consulted Lord Haldane who asked him the question “Do you believe that the more that social conditions are studied scientifically and impartially, the stronger the case for socialism becomes?” Sidney answered ‘yes’. “Very well, if you believe that, you are entitled to use the bequest for the starting of a school for scientific impartial study and teaching.” I’m not convinced that the same legal argument would be upheld today!

Beatrice and Sidney both lectured at the school in its early days, broadening the field of economics and particularly challenging the capitalist assumption that ‘pecuniary self-interest’ is the only driver of economic behaviour.

William Beveridge, who was Director of the LSE from 1919 to 1937, wrote later that “The School of Economics is the favourite child of the Webbs” and that “the School was a way to the object which always lay nearest to the hearts of the Webbs, the bringing about of social conditions, not by revolution or violence, but by application of reason and knowledge to human affairs.”

3. She was a key figure in the abolition of the Poor Law and workhouses

Before meeting Sidney, Beatrice had worked for Charles Booth and was shocked by the life patterns of the poor and destitute. She uncovered copious facts about the Poor Law and became passionate about the injustices of the Poor Law and particularly the underlying assumption that genuine unemployment among able bodied workers did not exist. She was appointed to the Royal Commission in 1905 but rapidly fell out with other members over their wish to maintain the underlying principles of the Poor Law. She carried out some independent research and, supported by 4 other committee members, produced a Minority Report in 1909 which came up with a radical set of proposals aimed at shifting the policy agenda from the relief of poverty to its prevention.

Her report recommended a “national minimum of civilised life” and put the responsibility for the conditions that created poverty firmly at the door of government rather than the individual. The report was widely circulated and discussed with leading politicians and described by Bernard Shaw as giving the ‘death blow to the Poor Law’.

The report was expertly researched and articulated, and Beatrice campaigned for its adoption, assisted by the young Beveridge, Greenwood and Attlee. It was many years later, during the war, that Coalition Minister, Greenwood, commissioned Beveridge to write his report, which Prime Minister, Attlee, subsequently brought into law.

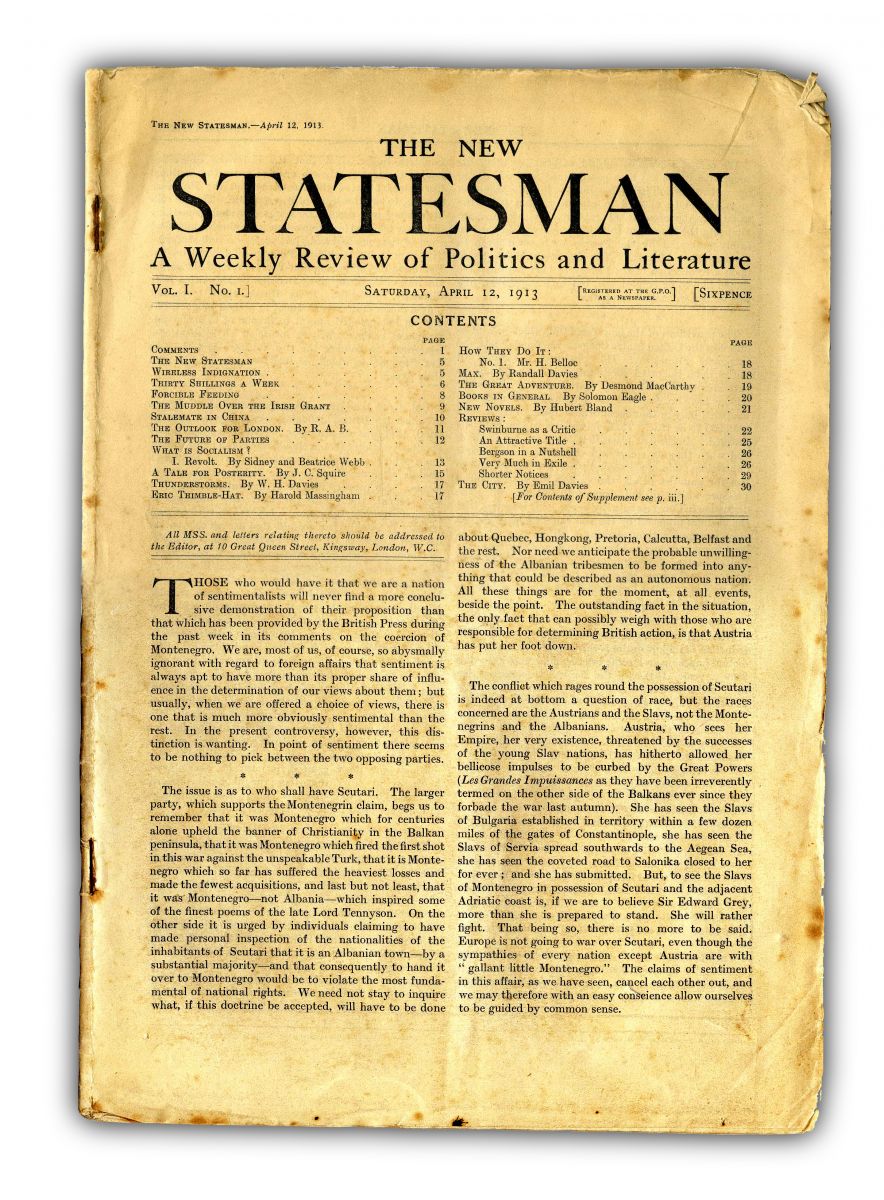

4. The Webbs founded the New Statesman

After all their hard work on the Minority Report and subsequent campaigning, the Webbs went on holiday to India and the Far East, and on their return felt that they needed a new impetus. They decided on the launch of a new weekly paper. They recruited subscribers in advance from all their acquaintances and from the card index system of the Fabian Society – in this way they got commitments from 2,500 people before the first issue. They also raised capital of £5k from private donations, of which Bernard Shaw contributed £1k, believing that this money would cover their losses for around 3 years – the paper was not expected to last beyond then.

The first edition of the New Statesman stated 3 clear principles: that it was not an organ of any political party, its policy was Fabian socialism and it was genuinely independent. Early editions included articles on foreign affairs, trade unions, national insurance and the treatment of suffragettes in prison.

It did rather better than 3 years – the rest is history….

5. She worked with all political parties in developing the post-war ‘welfare state’

GDH Cole wrote “the Minority report is the first full working out of the conception and policy of the welfare state, more comprehensive… than the Beveridge Report of 1942 which in many ways reproduces its ideas”. Clement Attlee, who had been Beatrice’s campaign manager, later described the Minority Report as “…. the seed from which later blossomed the welfare state”.

Among her many proposals were: a state education system available to all, a national healthcare system, pensions for the elderly, the transfer of social care responsibilities from the poor law guardians to local authority committees, a Minister of Labour with a national role to minimise unemployment, manage labour exchanges and ensure worker training, and unemployment insurance (although through trades unions rather than national insurance).

While many of her proposals in the Minority Report were not adopted at the time, these gradually came to fruition through the interwar years and particularly in the 1940s, led by Winston Churchill and subsequently Clement Attlee. Together they provide the foundation of the various elements of the ‘welfare state’ as we understand them today.

There is no doubt that the conditions under which the welfare state were set up have changed radically, particularly in the global forces shaping employment, multiculturalism and women’s role within society and the workforce. And, while Beatrice would probably be impressed by many aspects of life in the UK today, I’m sure she would be shocked by the inequalities in our society and the extent of poverty in many of our communities.

Crucially, while her proposals took some years to be implemented, Beatrice did much to provide the research, open up the debate and engender the public awareness and conscience which precedes major social change. We hope that the legacy that we leave as a Trust will help to do the same for poverty in the UK in 2017.

Co-authored by Baroness Diane Hayter, Webb Trustee, and Richard Rawes, Chair of Trustees

Posted on 21 Sep 2017 Categories: About Beatrice