Young people and inequalities: start from where they’re at

Posted on 14 Jul 2021 Categories: Blog, Inequality, Local initiatives, Young people

by Caroline Hartnell

Even before the pandemic, young people in the UK faced many forms of inequality: a lack of jobs, a shortage of affordable housing, and cuts to public services – and growing mental health problems. The pandemic has exacerbated these problems and widened the gap between generations still further. What can be done to tackle those inequalities? This was the question put to three young leaders, who are working in and beyond their local communities to address inequalities in education, housing, employment and the criminal justice system, as part of LSE’s panel discussion on ‘Youth and inequalities in the UK’ on 29 June.

One huge barrier to tackling these inequalities is the lack of understanding of the lives of disadvantaged young people. A point made several times during the discussion is that for many young people from disadvantaged backgrounds ‘one of the main occasions when they meet the upper classes is in court’. ‘These are people who have no idea of what these young people are experiencing,’ says Michaela Rafferty, youth engagement and campaigns organiser at Just for Kids Law, who grew up in Belfast.

Understanding young people’s lives

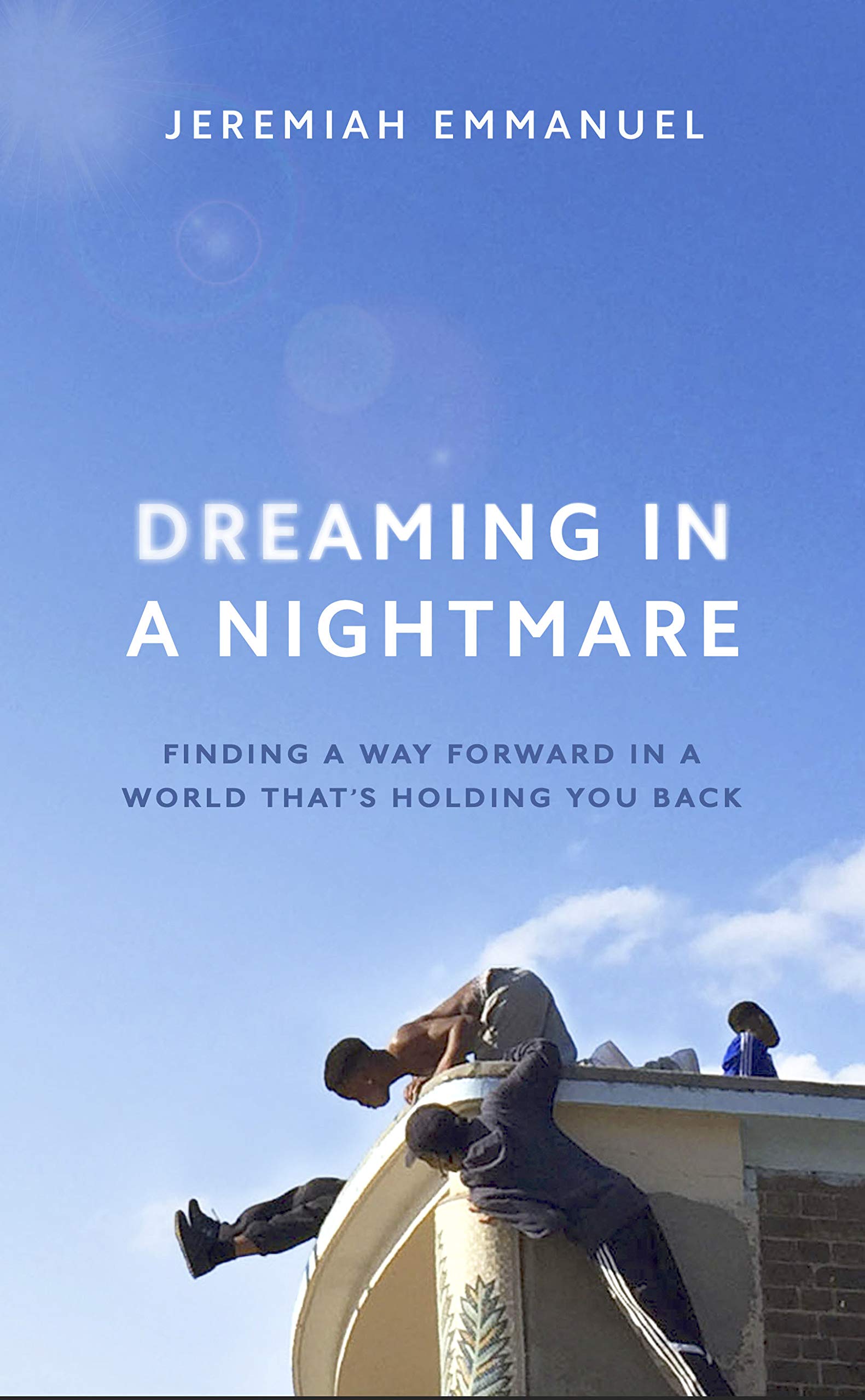

Brought up in Brixton in south London, Jeremiah Emmanuel entered youth politics in his early teens. He was elected into the UK Youth Parliament and later became a young mayor. Dreaming in a Nightmare is the title of his new book. Was Brixton the nightmare? No, he says, he experienced his environment as quite pleasant, although he was surrounded by inequality. ‘The reason for the title was that the reality of what me and my friends experienced could be seen as a nightmare to someone else. We didn’t see it.’

Brought up in Brixton in south London, Jeremiah Emmanuel entered youth politics in his early teens. He was elected into the UK Youth Parliament and later became a young mayor. Dreaming in a Nightmare is the title of his new book. Was Brixton the nightmare? No, he says, he experienced his environment as quite pleasant, although he was surrounded by inequality. ‘The reason for the title was that the reality of what me and my friends experienced could be seen as a nightmare to someone else. We didn’t see it.’

As a young black boy, for Jeremiah being stopped and searched by the police was normal. ‘One day I was at 10 Downing St at a reception to celebrate activists; a few days later I was in the back of a police van. It was normal. Others saw it as so unfair this had to happen to me.’

Recognition that he lived ‘in a city of two worlds’ where people were living ‘parallel lives’ came aged 9 on a trip on the 345 bus, which went from Brixton to Clapham and Battersea, ending in Chelsea. For the first time he saw clean pavements, and cars and houses such as he’d never seen before.

He remembers going to the school careers adviser and saying he wanted to be an author. ‘Don’t be too ambitious,’ said the adviser. ‘Yet those attending public schools were prepped to be CEOs, prime ministers.’

Social modelling approach: start from where they’re at

Understanding the lives of disadvantaged young people is central to Jason Allen’s job running St Mary’s Centre in Camden, which works with young people aged 12-25 facing violence and exclusion. The approach he has developed draws heavily on his own experiences. At age 15 he was put in adult hostels. He became involved in crime and was excluded from education, both through formal exclusion and by being put in classes for disruptive children. At 18 or 19, he says, he became angry and involved in violence. ‘I didn’t know why life was like it was.’

Then he struck lucky. He became involved with St Mary’s and ‘someone on a youth programme gave me the chance to run something’. But one year into his employment he got caught up in past issues and got stabbed quite badly. But ‘the Mary people didn’t judge me’ and he helped rebuild the project on a social modelling approach. This started with the question: what didn’t he have as a young person?

Jason remembers as a child having no one to turn to. The government narrative, he says, is ‘we want to stop youth violence’ but what is offered is ‘tokenistic youth programmes for 6 weeks’ and ‘not much preventive work with young people actually at risk – encountering violence, going to County Lines. Once engaged in the criminal justice system, it’s a slippery slope thereafter.’

St Mary’s by contrast offers 24-hour access to caseworkers every day of the year. The project is open at night for hardened gang members. ‘We can work with a young person for 5 hours in one week or one hour every 3 weeks. We will go to young people where they are – at the centre, in parks, in people’s houses, in police stations.’ Over 15 years, he says, they have made headway with children excluded from school, involved in drug taking, etc. They get ‘intel’ about things about to blow up. They offer ‘countless mediations’. They are now able to be more preventive, working with schools in the borough with children struggling in classrooms. The 11 caseworkers are enabling individual young people to ‘speak up for themselves in different situations’.

Michaela too talks of the ‘isolation facing young people living on the margins of society. We need to devise systems for them not try to make them fit in,’ she says.

Finding alternatives to school exclusion

Just for Kids Law provides kids in London with legal representation. In England 7,800 children are permanently excluded from school each year, while a massive number experience temporary exclusions. Young people who are already vulnerable are more likely to be excluded, says Michaela. Those with SEN (special educational needs) are six times more likely to be excluded; those on free school meals are four times more likely to be excluded; those from black and ethnic minority backgrounds are three times more likely.

The appeals process has been impossible to navigate since 2012, she says, with no legal aid available. Many young people have no idea of their rights, for example in relation to exclusion. ‘We need a complete overhaul, to understand what young people need if they are to realise their full potential.’

Asked by an audience member what she suggests instead of exclusion, Michaela returns to an earlier point. ‘We need to look at the young people most affected. The starting point would be understanding what their lives are like. We need trauma training, mental health training, generally more resources put into schools.’ Of course funding is needed for this, but ‘we need to understand why young people become involved in gangs rather than continuing to push them to the margins of society’.

Jeremiah mentions a policy of zero exclusions instituted by Dunraven School in Streatham in south London, where teachers were trying to find the underlying issues behind medium and low level exclusion. ‘The problem with many schools is that they don’t want children who won’t get good grades.’

Changing the narrative

Another issue, says Jason, is how to change the narrative and counter the idea of ‘problem families’, that certain young people are ‘alien and we can’t do anything for them’, which cripples so many young people from a young age. Upper-class families with children at boarding schools may need counselling and mentors, but this isn’t highlighted as a problem in society. In Camden Town the problem is the drug sellers, not wealthy young people coming in to buy the drugs.

People with adverse childhood conditions experience great stress and trauma, he emphasises. ‘Young people are not big bad wolves. We need to look at the root causes of violence. We need a greater understanding that families are not always the problem, and parents could help their children if they had more help.’

Lack of services for young people

This is another big issue. When he was growing up, says Jeremiah, youth services were cut. The local McDonalds became the youth club. ‘We need to find new ways of providing youth support, to invest in communities and young people so the cycle doesn’t continue.’ Politicians tend to think about problems they experienced as young people 25 years ago, and from very different backgrounds.

There are also social barriers to young people accessing counselling, says Jason. Some young people see it as a sign of weakness; there is a stigma surrounding it. This isn’t helped by the huge gulf between disadvantaged young people and those providing counselling. Too few understand the issues young people are going through. Out of 40 who trained with him at the Tavistock Institute, he says, only three were males and 36 were white. ‘Young black boys need role models. Counsellors need to be more representative of the communities young people come from.’

Counselling services also need to be more flexible, he says. ‘Waiting lists are ridiculous. If a young person is experiencing trauma, for example someone they know has been murdered, they need crisis/contingency sessions.’ St Mary’s Centre offers counselling services within their 24/7 model.

‘We need to meet young people where they’re at,’ Michaela says in summary. A lot of excluded young people say: if only teachers/others had presented me with solutions at the time, given me a chance. They weren’t able to represent themselves, didn’t know what their rights are. ‘If the dominant narrative tells people not to expect too much, it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.’

Click here to watch the whole session.

Want to keep up-to-date with more articles like this? Sign up to our newsletter.

Posted on 14 Jul 2021 Categories: Blog, Inequality, Local initiatives, Young people