How to make elite power listen to the people? Organise

Posted on 10 Jun 2020 Categories: Blog, Climate crisis, Coronavirus

by James Morrison-Knight

‘If I’m honest I am just tired

Tired of everyday filling up my car and

Knowing that I’m paying for the bombs in Iraq

Tired of pretending like it don’t hurt my heart

Of wanting change but not knowing where to start’

Akala, Find No Enemy

The lyrics above from the musician Akala capture the feeling of distress at the seemingly endless crises of the world, as well as recognising one’s own responsibility, but ultimately feeling alone and powerless to do anything. Indeed, as individuals there is next to nothing that we can do to challenge entrenched elite power. Yet, when we come together in collective, democratic movements, we can hold elites to account and take back the power.

Powerful interests taking advantage of times of crisis

The Covid-19 crisis has laid bare the inherent flaws within our global economic system, as financial markets crash around the globe, bringing humanity to a crossroads. Karl Polanyi, at the end of his book The Great Transformation, puts forward two possible paths that can be taken: either private power is preserved in tandem with increasing surveillance and a more coercive state at the expense of democracy, or we transform our society into one that is more democratic and just at the expense of market society. Powerful interests are vying to ensure the former is the route taken. In a recent article on Rethinking Poverty, Barry Knight outlines how elites are using the ‘shock doctrine’, a term coined by Naomi Klein, to take advantage of the disruption of crisis moments to push through nefarious laws and policies that ultimately benefit themselves and result in devastating consequences for others.

Since that article was published, we have seen the economic crisis induced by the coronavirus crisis being exploited by opportunistic disaster capitalists. In the past few weeks, as states have rolled out lockdowns and other measures, the gears of economies have stopped turning. Stock markets have repeatedly crashed in spectacular fashion, already surpassing the crash of 2008. The investment firm of Jacob Rees-Mogg, a Tory MP and leader of the House of Commons, is already exploiting the low value of shares around the globe to profit from the chaos. Multinational corporations that systematically dodge taxes, such as airlines, are queuing with outstretched hands to receive bailouts, while at the same time it has been reported that in one day in Britain a million and a half people went hungry because they had no money or access to food.

Democracy, which is already threatened, may suffer further. This crisis is being used as an excuse by leaders with dictatorial tendencies to further tighten their stranglehold on politics. The Hungarian prime minister, Viktor Orbán, after years of systematically dismantling democratic structures, as well as stoking right-wing nationalistic sentiments, has finally got his way, thanks to the Covid-19 crisis, and now rules the country by decree. In many other countries, governments are proposing to reduce the spread of the virus by using smartphone apps to track people’s movements – the dangerous implication being that the apps could become a permanent feature after the crisis, an element of Polanyi’s vision of an undemocratic surveillance society.

On the environmental front, insidious forces are at work. In one of the most disturbing pieces of recent news, the oil industry is taking advantage of the coronavirus pandemic to finally build the highly controversial Keystone XL pipeline. One of the main reasons that it has not been constructed before now is because 30,000 trained non-violent protesters would block its construction. But, now that the US is in lockdown and the protestors are unable to protest, Big Oil has seized the opportunity to push forward with the construction of the pipeline, flying in workers from all over the US who they deem to be ‘critical workers’, despite the fact that the world is swimming in oil and oil prices are at an all-time low. On 15 April, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) gutted an Obama administration regulation requiring coal plants to cut their emissions of mercury and other pollutants.

‘What can I do about this?’

These seemingly endless crises can be overwhelming. They leave one feeling powerless and helpless to do anything. We feel responsible for what is taking place around the globe, but alone and without guidance.

This mode of thinking arguably has its roots in four decades of neoliberalism, which has drilled into us that we are individually responsible for the problems of the world; that as consumers we have enormous power at our fingertips and we need to be responsible with our purchases. The narrative has emerged that if we just buy fair trade food, recycle our plastic and donate £1 a month to charity, then the world will be fine and dandy. This mode of thinking has permeated the minds of many around the globe. However, a few years ago a sustainable lifestyle blogger, Alden Wicker, shocked the UN Youth Delegation by telling them that ‘conscientious consumerism is a lie’. As she explains: ‘making a series of small, ethical purchasing decisions while ignoring the structural incentives for companies’ unsustainable business models won’t change the world as quickly as we want. It just makes us feel better about ourselves.’ While, undoubtedly, we should be conscious and moral consumers, the problem is that we have been duped into thinking that we, as consumers, have power to leverage change.

Collective action

When we change the ‘I’ to ‘we’, there is huge potential for what can be achieved. Naomi Klein laments that after giving talks about how the neoliberal economic model has both enabled the exploitation of people around the globe and drastically increased greenhouse gas emissions, people in western audiences consistently ask ‘what can I do, as an individual, to change the world?’ Her answer is straightforward: ‘Nothing. You can’t do anything. In fact, the very idea that we, as atomized individuals, could play a significant part in stabilizing the planet’s climate system or changing the global economy is objectively nuts. We can only meet this tremendous challenge together, as part of a massive and organized global movement.’ Indeed, there is little point in trying to do anything as an individual. But when we organise collectively, then we can change from powerless individuals to powerful movements.

The power of mass movements

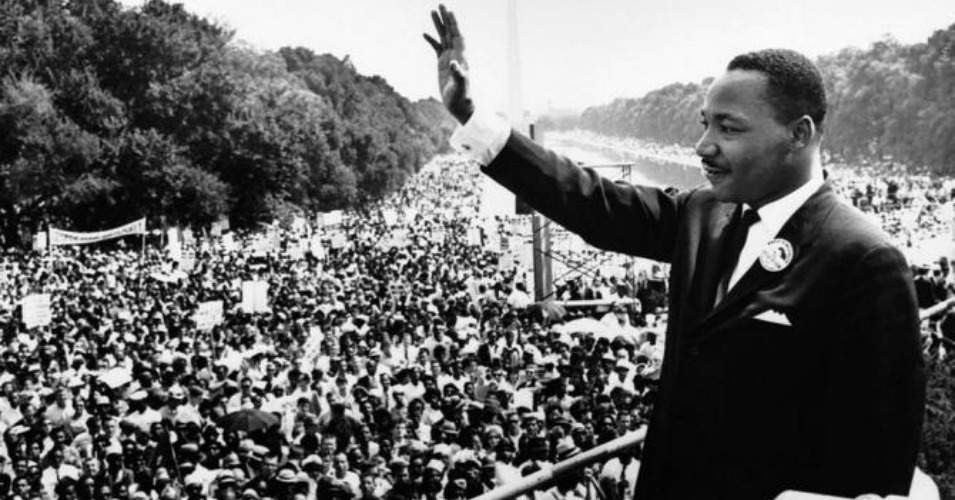

Mass movements of people are the most effective vehicle for change, as history shows. In the past, when elites maintained unjust and imbalanced institutions that served their own needs at the expense of the majority, it was ordinary people that coalesced into mass movements to fight back. The labour movement emerged in response to appalling working and living conditions of the majority population. It was brutally suppressed for centuries, but eventually gained legal status. Strikes such as the 1889 London dock workers strike laid the foundations for the expansion of the trade union movement, which later led to the creation of the Labour Party. The suffragettes, similarly, were attacked by the state and by the media at the time, yet through direct action won the right for women to vote. It was the Indian Independence movement’s use of mass non-violent direct action to combat a ruthless and violent colonial power that led to the victory they sought. The same tactics were famously applied by Dr Martin Luther King in the Civil Rights movement, defying a cruel, racist state to advance human progress. Nowadays we take these victories for granted. We enjoy basic working protections, women and people of colour have the right to vote, and we live in a world mostly not directly ruled through colonialism. All of these are democratic victories, conferring democratic rights on people all over the world and won by democratic movements – masses of people – standing up against archaic power structures.

Are some actions more powerful than others?

Some actions are clearly far more effective than others. Towards the end of 2019 a million people descended on London to demand a final say on Brexit. They marched peacefully past Westminster and the protest was described as one of the ‘biggest marches in British history’. Did it make a difference? Not in the slightest. The conservative government took no notice and scrambled to get a last-minute agreement pushed through parliament.

Earlier that year, there was another massive protest in London. In April Extinction Rebellion (XR) launched the International Rebellion, locking down key locations in the centre of the city. They used the tactic of non-violent direct action and over 1,000 people were arrested. Their demands were for the government to ‘tell the truth’ and declare a climate emergency, legally committing the government to net zero carbon emissions by 2025, and for a citizens’ assembly to be created to supervise this. Did it work? Yes: about a week or so after the action the UK parliament declared a climate emergency. It may only have been a small victory, but it was a victory against elite power, nonetheless.

Challenging power structures

A protest cannot challenge power in the way that a direct action can. A demonstration or protest, such as the Brexit march, where masses of people march through the streets holding placards and chanting slogans looks great in newspapers and on TV. However this type of protest doesn’t disrupt economic and other social activities. As a result little attention was paid to the protesters by those in positions of power, and their demands went unheard. This contrasts with disruptive actions, such as the April 2019 Rebellion by XR, where people put themselves on the line, blocking roads, gluing themselves to buildings and getting arrested, which inevitably disrupts normality and challenges the status quo. Politicians were faced with people actively defying the law, stretching the police to their limits and costing a lot of money. And it worked: the government gave in to at least some of their demands.

In order to challenge the status quo, people have to actively challenge the institutions that maintain it. Conventional protests are powerful when protesting itself is forbidden, as with the Arab Spring or Tiananmen Square. However, in liberal democracies a conventional protest falls into the category of what is allowed, and so does not defy the power of elites.

The power of organising

Successfully implemented direct action doesn’t take place spontaneously; it is the culmination of a long process of organising. Jane McAlevey, in her 2016 book No Shortcuts: Organising for Power, provides an invaluable discussion on the topic. Although she writes from the perspective of trade unions, what she says can be applied to other forms of organising. Organising, she says, relies on a growing body of workers taking action – not just the usual suspects, but people that don’t see themselves as activists’. It is a highly democratic approach, attempting to ensure the participation of as many people as possible in decision-making processes and therefore putting workers in the driver’s seat. This time- and labour-intensive process pays off in a strike, which can succeed only when a majority of workers walk off the job with the support of their broader community.

Without solidarity, direct action can’t work. When workers walk off the job, they need to be sure that an overwhelming majority of their fellow workers will do the same and that the risk is worthwhile. If they decide individually that they don’t trust their fellows and it is not worth the risk, then the strike will fail. Similarly, when people engaging in non-violent direct action chain themselves to a building they need to know that their peers will be there to support them throughout the action and afterwards. If they don’t feel the solidarity among the group and choose not to take the risk, then the action will fail.

This can be compared with Rousseau’s allegory of the stag hunt dilemma, where a group of hunters track a stag in the forest. They all face a personal decision: if they work together as a team they can kill the stag and eat for days, but if even one hunter decides to break away from the group to instead hunt a hare (a hare is easier to catch but will only satisfy the hunter for one meal) then the deer hunt will fail. Thus, solidarity relies on the decisions of individuals as to whether they can trust their group and the risk is worth taking.

Extinction Rebellion are currently demonstrating the power of organising. It may seem that the movement burst onto the scene out of nowhere, yet it took a lot of careful study, planning and organising. Their decentralised, democratic approach to organising and a commitment to try to include everyone is working. The dedication of ordinary people willing to defy the law and get arrested is proof enough of their achievements in terms of organising. What’s more, their non-violent tactics, and their success in pressuring the government to declare a climate emergency, meant that their support increased fourfold after the April 2019 rebellion.

There’s work to be done

It may not be news that the wealthy and the powerful will look out for themselves at the expense of others. We may feel powerless in the face of their power, but we need not despair: when we act collectively in democratic movements, we can begin to reclaim power from the few that hold it. When the Covid-19 lockdown is over, then we will need to fight back against the powers that be harder than ever in order to ensure that we #BuildBackBetter rather than returning to business as usual. In the meantime, we can’t wait to be able to organise face to face: we need to utilise technology and find ways of creating solidarity online.

The eruption of Black Lives Matter protests currently ongoing across the US will undoubtedly be worrying those in power, and for good reason. The latest story of police brutality has ignited a firestorm that has been brewing for a long time. The flames will be hard to quench. Centuries of racism, injustice and inequality have culminated in this expression of anger and now those on the streets are demanding change. Steps towards justice are being made: Derek Chauvin has been charged with murder, though whether he is convicted remains to be seen; the state of Colarado has already adopted legislation requiring police to wear bodycams, banning chokeholds and improving transparency, and the Minneapolis city council has pledged to disband the city’s police department. In the short term these protests may lead to reforms in policing, but should they become sustained organising efforts, then there is the potential that there could be a transformation of the current injustices into a fairer society for all.

James Morrison-Knight has previously worked as a union organiser.

Want to keep up-to-date with our coronavirus coverage? Sign up to our newsletter.

Posted on 10 Jun 2020 Categories: Blog, Climate crisis, Coronavirus