Super-Policies: New Thinking To #BuildBackBetter

Posted on 26 Aug 2020 Categories: Blog, Coronavirus, Cross-posts, Wellbeing

by Jennifer Wallace

The Carnegie UK Trust works to improve personal, community and societal wellbeing. Many of the issues that we work on, and the partners and groups who we work with, are deeply affected by the impact of the COVID-19 crisis. Over the coming weeks we’ll be sharing a series of blogs with reflections and questions across these different aspects of wellbeing. We are interested in learning from others, so please get in touch to share your reflections on how communities, networks and organisations are responding.

I have worked in wellbeing policy for the best part of a decade now. It has been a fascinating and exciting field to be part of – cutting across the traditional silos of academic or public sector thinking. But too often when asked what could or would be different, we have grand theories but not practical, implementable policies. Many reports and reviews now call for a “Beyond GDP” approach to measuring social progress, but what happens once you have measured what matters… how do you take that learning into real world decisions?

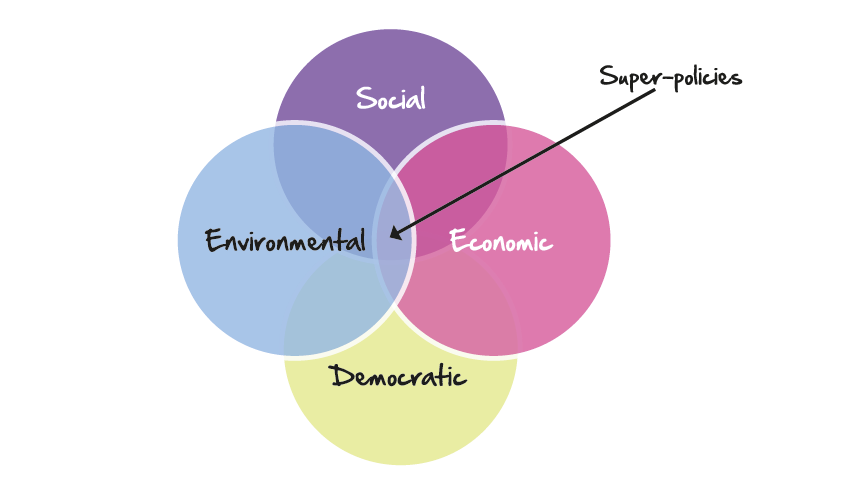

Too often the conversation is set at the level of a largely theoretical argument: the economy versus environmental, or social, or democratic outcomes. We do need to have this conversation – national GDP has no predictive power over improving personal wellbeing and there are multiple examples of the pursuit of GDP being in direct conflict with global and local environmental concerns. But we also need to move beyond the theoretical, towards clear and implementable policy ‘asks’.

Given the way that the conversation has shifted during the pandemic, it certainly feels like the wellbeing arguments are close to a tipping point. And while we shouldn’t stop making the argument as clearly as we can, we also need to boost our recovery from the pandemic with new ways of thinking and acting amongst all kinds of decision-makers. Away from conversations about measurement, statistics, we need to inspire creativity across society.

Borrowing from health – we need wellbeing in all policies. Towards the end of last year, Gerry McCartney introduced me to the concept of super-policies. Gerry and his colleagues define super-policies as:

Policies that achieve positive outcomes across a wide range of areas beyond that which was the primary intention, and which do not have unintended negative outcomes.

In his work, this related specifically to public health. But it struck me then that the concept has a lot to offer those of us who are searching for a way to ‘operationalise’ wellbeing at all levels of decision-making. If the key issue is that those working in the field of the economy think that the environmental, democratic or social outcomes are someone else’s ‘domain’ (and vice versa) we need an easy way to capture their attention.

The advantage of this definition of a super-policy is that it does not expect people to put down their primary intentions; it does not expect headteachers to stop seeing education as their primary concern, or town centre managers to become experts in anti-poverty strategies. It merely asks them to build in additional outcomes that could reasonably be achieved, or to mitigate negative outcomes that emerge in other domains.

From a wellbeing perspective, while it is relatively easy to think of policies that have one additional benefit (eco-schools for example), it is much harder to identify existing super-policies that work across all four domains of wellbeing (see figure 1). In fact, I found it hard to think of any.

Community businesses are the clearest example I could think of. Here local people (democracy) come together to buy or manage a tangible asset creating economic outcomes. These build community cohesion (social) and often have direct and indirect environmental benefits (renewable energy, provision of local services to reduce car use for example).

Active travel is one policy that also comes close. It has health benefits (social); reduces reliance on cars (environmental); puts more money in your pocket and in local businesses, and potentially requires investment in infrastructure (economic). The redistribution of space can be seen as democratising in itself, but to be a super-policy it would have to have a ‘voice’ element, perhaps local deliberation on priorities for active travel investment, or community organisations’ involvement in the promotion of active travel routes? In some areas this already happens, but this thought process challenges decision-makers to question whether they have gone far enough.

Having identified two, and on a roll, I started wondering about others, like how to reduce landfill by encouraging use of more environmentally friendly period products and reusable nappies. A key barrier is women’s reluctance to shift their product use. Again, a voice element could help better understand their perspectives, and build solutions around their needs. Provision of sustainable products as a basic health service could be built into the practices of GPs and pharmacies (social); the Scottish baby box could put eco-friendly products in the hands of a new generation of mums for the first time. There are clear economic benefits in terms of the costs of these products.

These are just three ideas… there will be hundreds more potential ones out there… so in the spirit of democracy… what would you put on the super-policy menu for #BuildBackBetter?

Jennifer Wallace is Head of Policy at Carnegie UK Trust

This was originally posted on the Carnegie UK Trust blog on June 26th 2020.

Want to keep up-to-date with our coronavirus coverage? Sign up to our newsletter.

Posted on 26 Aug 2020 Categories: Blog, Coronavirus, Cross-posts, Wellbeing