Money and its uses

Posted on 27 Feb 2019 Categories: Blog, New economic models, Social Security

by Donald Burling

Rethinking Poverty encourages its readers to contribute their thoughts so that we can all engage in developing the society we want. Here we publish an article by Donald Burling that suggests a way of creating money to boost the local economy by increasing the spending power of people on low incomes. The article is based on an experiment in Austria in 1932.

This is an interesting suggestion given that since 2008 the £445 billion extra money created through quantitative easing has increased asset prices and so boosted the incomes of the top 5 per cent by as much as £128,000 each, yet has nothing for the poor (see Strategic Quantitative Easing, p28, by the New Economics Foundation). This article shows how things could be done differently, benefiting the poor rather than the wealthiest in society.

If money is so short, why don’t we just make some more? Money after all is artificial and can be created at will. If we create too much it causes inflation, but in moderation it can make life easier for everyone.

The banks have in fact been doing this for years. All the money they lend out finds its way back into the banking system and can be lent out again. The trouble is that when banks create money they also create debt, on which interest has to be paid. I once asked Oliver Letwin: If all the money in the world earns interest, where does all the money to pay the interest come from? His answer was that it had to come from increasing the money supply. But if the only way the money supply is increased is by bank lending, that means more debt and more demand for interest.

During the 1950s and 1960s, the nationally owned Bank of England regularly provided the government with money as it required. There was a relaxed attitude to inflation, which ran at around 10 per cent per annum. Those with savings saw them shrink in real value, but as wages rose faster than prices, for most people it was a time of prosperity. The financial discipline imposed by the Thatcher government changed all that.

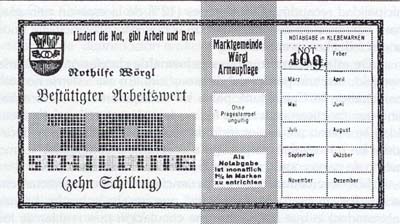

In 1932 the town of Wörgl in Austria was in a bad way. Unemployment was over 25 per cent, people could not afford to pay their taxes and the town council could not afford to pay its workers. The mayor hit on the idea of issuing a local currency of ‘free shillings’ with the requirement that anyone holding them at the end of the month had to pay a 1 per cent stamp duty. Thus there was an incentive to spend them as fast as possible. The effect was remarkable: taxes were paid, and unemployed people were set to work on public projects including the building of a new bridge.

Such was the success of the scheme that many other towns wanted to follow it. But the central bank stepped in and had such schemes declared illegal, thus returning unemployment to its ‘normal’ level of 25 per cent. Arguably this paved the way for Hitler to impose his own ‘solutions’.

If money were to be created, how should it be used? Care would be needed, for money thrown at problems quickly disappears.

But there are some obvious first steps. The benefits system, including Universal Credit, clearly needs to be made more generous. Local authorities have been squeezed unreasonably, and the grants they used to make to voluntary organisations have all but disappeared. There needs to be a levelling up of wages, starting with the removal of the restrictions on public service pay. As more people have money to spend, businesses will benefit.

Donald Burling describes himself as a ‘One Nation Conservative’ and author of a book called Brain-Storm which presented a ‘clowns-eye view’ of current affairs in the 1990s. He is also a committed Christian and a writer of gospel songs.

Rethinking Poverty is interested in developing a range of methods for poverty-proofing investment policies of the state. Please send us your ideas to contribute to this discussion. Write to carolinehartnell@gmail.com

Posted on 27 Feb 2019 Categories: Blog, New economic models, Social Security