Making markets work for the common good

Posted on 30 Dec 2020 Categories: Blog, Cross-posts, New economic models, The state we want

by Andrew Milner, Lisa Jordan and Stef van Dongen

As the pandemic has stood the world on its head, one of the debates which has been thrown wide open is that of the future of the economy. PSJP has therefore launched an inquiry into how markets can be made to work for the common good and how economies can be made to serve the general interest, rather than that of the few. The first step has been a series of conversations with people who are working towards an economy for the common good. For this first blog we review the wide-ranging thoughts and ideas that emerged from the interviews with Barry Knight, Frans Geraedts, Simon Zadek, Nicholas Colloff, Christina Hollenback and Tatiana Glad.

Alignment among the alternatives

Probably the main thing to emerge from all conversations is the need for alliance among those on the progressive side of the argument. There are plenty of blueprints for an alternative economy making markets work for the common good and some of these were floated in a background document to the conversations: the Green New Deals (of varying shades of green), Donut Economics (meeting needs without overshooting the limits of what the planet can provide), the similarly named Good Economy and Economy for the Common Good, both of which stress community, democracy and sustainable consumption. What surfaced repeatedly in the conversations is that there is very little contact between them and even less common cause. At times, they are more or less open divisions. Tatiana Glad of the Amsterdam Impact Hub sees such a divide between the more traditional bigger picture economic thinkers and those involved in social enterprise or business. This fragmentation is unhelpful. ‘For a new economy we need new mental models; they (the thinkers) are not immersing themselves in the living context of the innovators.” To make headway, their proponents will need to organise. As Frans Geraedts pointed out, while those who support the status quo aren’t necessarily organised they are at least agreed on the fundamentals of their position. One of the first things needed therefore is alignment among the alternatives. If that’s step 1, step 2 should be to create a narrative of alternative economic models that not only unites the progressives, but is also forceful enough to influence mainstream thinking, believes Barry Knight of CENTRIS and author of Rethinking Poverty. He points out that mainstream thinkers tend to be thinking very conservatively and the chances of a new model emerging without pressure and without influential allies are remote. For him, one of the virtues of PSJP’s project is to do exactly that – to bring new ideas together.

‘For a new economy we need new mental models; they (the thinkers) are not immersing themselves in the living context of the innovators.”

More than coalition of the willing, a coalition of the hitherto reluctant…

To create momentum, therefore, not only those who are pushing the new ideas need to come together, but also civil society, and within that the labour movement – above all – to organize for government power. As usual, a central problem in changing the status quo is that those who are most convinced of the need for change have the least power to make it. Only government can enforce its edicts because of its monopoly of force. Government has to be part of the coalition or we lose. At the moment and for the last 40 years, argues Geraedts it has been dominated in the western world by centre-right parties and coalitions. We need a shift to the centre left. And there are formidable obstacles. He notes what he calls a wicked triad of oligarchy, autocracy and xenophobia. Anything that threatens vested interests will be subject sooner or later to a backlash from those interests.

Simon Zadek (who until recently was on the UN Secretary General’s Task Force on Digital Financing of the Sustainable Development Goals), too, believes we do wrong to discount the role of the state, not only for the sake of its authority, but he also suggests that it might have something to offer in terms of economic alternatives, with hybrid corporate governance models that allow for state ownership of assets. State-owned models of capital and industry aren’t necessarily good but, he argues, they contain patterns of change that might be both good and bad.

Working in the current system won’t do

Social enterprise, impact investing, B-Corps and so on are just a more acceptable face of the present system… and they will be absorbed by it. Even if the social business sector were to expand massively, what’s needed, Zadek argues, is system change and you won’t get that by aggregation – more and more social enterprises, more and more socially responsible investing or socially responsible companies. For him, that’s ‘trying to fit tomorrow into a nicer version of yesterday’s box’.

Similarly, Nicholas Colloff, Executive Director at Argidius Foundation feels that impact investing is a marginal activity based on the seductive idea that you can have your cake and eat it. It’s not a market maker, it’s a player in a market system which is fundamentally unstable.

Local, not global

The blanket term ‘market’ often masks misconceptions about the relationship between finance and what Colloff refers to as the real economy, the economy of goods and services. Even politicians, he says, often don’t understand finance or how the two relate, or do not relate, to each other.

Money needs to get cheaper and more difficult to obtain. We need to take money out of the system (which involves large-scale debt relief) and tether it to the real economy. He offers a historic example of Switzerland. Each Swiss canton (administrative region) had its own regional bank, owned by the canton so it didn’t have to maximize profits and it could lend primarily within the canton. This created a pool of ‘sticky’, low-cost money. The bank was there to make the economy viable in the community it serves. Could this model be extended to other countries, especially those in the developing world, where regional, state-owned banks would drive local economies? Other ideas along these lines to emerge from the discussions were that of a long-term stock exchange or closed capital circles where money stays in a pot for a long time and patient capital is generated.

At the moment, the financial system is by its nature extractive and based on individual interest, so it’s at odds with the community idea of solidarity and of regeneration. Publicly listed companies, which is where most of investment money goes, are subject to the demands of shareholders to maximise profits. It needs a crisis to change this way of thinking and to prepare the way for a different economic model, but – and here he echoes what others said about the need to create a narrative which is both coherent and persuasive – alternative ways of thinking need to be current before the crisis happens. He believes that a lot of work is still needed to explore what a financial system which supports a regenerative economy looks like and it needs to come from a credible source.

At the moment, the financial system is by its nature extractive and based on individual interest, so it’s at odds with the community idea of solidarity and of regeneration.

However, Christina Hollenback, founding Chair of the NEXUS network’s working group toward equal justice, believes that much can be accomplished in economic and social transformation by using the power of money. She is especially hopeful that next-generation wealth holders want to use that wealth to shift the dynamics. Significantly, she thinks that they are more willing to stand shoulder to shoulder with communities than their parents (in what she calls ‘proximity’). As a result of such concerted action over the Dakota Access Pipeline, JP Morgan, for instance, now listens to this group. Internal pressure from wealth holders through their resources is destabilising and can turn an investment into a distressed asset. If you can bring wealth-holders together and present a united front, it scares wealth managers, she argues. A sign of how anxious they are about the use next gens will put their money to is the time and energy they put into wooing them. With their collective power, they can make a difference and they are only just waking up to the fact. She also noted an interesting reconfiguration of forces. Those who had campaigned against the pipeline had a better understanding of the financial pain points than others. Parallel more investors began being more open to financial campaigns and impact investing approaches on a variety of issues when there were no political options left. The case had been a striking illustration of the potential power of private money to make change for the better.

We have already heard Colloff’s view on the possible value of local banks. ‘The idea of globalisation in the exchange of goods and ideas is fantastic,’ he says, ‘the notion of globalisation in the exchange of finance is a disaster.’ Hollenback also stresses the local, advocating what she calls ‘hyperlocal ecosystems’ which she sees as moving back to local ownership of formerly indigenous assets. ‘We need to develop the infrastructure to build capacity in proximate communities and we need to ensure that capital stays in that community.’

‘We need to develop the infrastructure to build capacity in proximate communities and we need to ensure that capital stays in that community.’

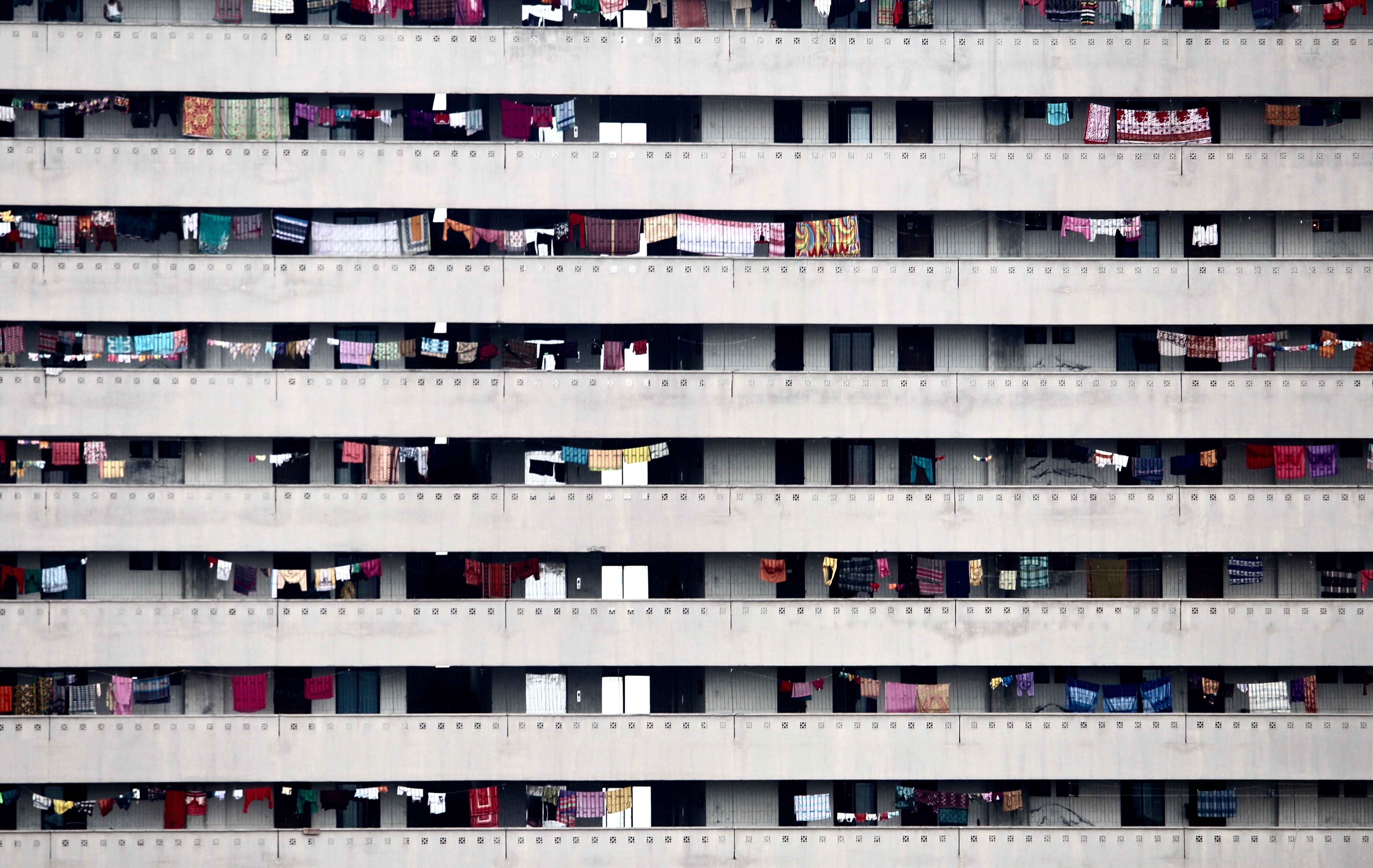

Moreover, it is at the local level that you are more likely to produce a set of economic relationships that meet people’s needs which, as Knight suggests, is at the heart of this discussion. This is central to PSJP’s interest in the issue. The market or the economy is not something separate from society and notions of justice but integral to it. How do we get an economy that works for people rather than having people working for the economy? Hollenback also touches on this, citing the example of Push Buffalo which is a clean energy generating enterprise run by refugees of colour and which has an explicit racial justice element.

Where to next? The importance of story

Perhaps most important of all, the proponents of alternative economic models need to make common cause, tell common stories and make those stories persuasive enough to convince people who run mainstream economies not only to take them seriously, but to embrace them.

Who should design and drive an economic framework for markets that works for the common good?

What visual framework can be the dashboard for our governance mechanisms? How can we tie financial markets to the real economy, internalise externalities and leave nobody behind? Any action will need to involve the government. Only governments have the power to make big change happen at sufficient scale and with sufficient speed.

… most important of all, the proponents of alternative economic models need to make common cause, tell common stories and make those stories persuasive enough to convince people who run mainstream economies not only to take them seriously, but to embrace them.

The next step will be a publication of a collection of essays building upon these ideas and providing practical steps towards implementation. As Knight suggested, this might help to crystallise the common agenda that the progressive economy needs. Indeed, the importance of using stories surfaced more than once in the discussions. Colloff suggested stories should be used to educate politicians about the economy rather than charts and figures. Glad makes an important point about this. It’s crucial, she believes, that the emphasis of the publication should be on stories that give people hope, the human behind the persona. She does right to stress the essential humanity of the debate because it is so often absent or simply assumed in discussions about the economy.

PSJP encourages anyone interested in helping to develop and expand these ideas on making markets work for the common good to join in. The first port of call is this website.

Andrew Milner is a freelance writer, researcher and editor specializing in the areas of philanthropy and civil society. He is a consultant to Philanthropy for Social Justice and Peace. He is also a regular contributor to, and associate editor of, Alliance magazine.

Lisa Jordan is a senior philanthropic executive with a twenty year career focused on impact and systemic change. She is the founder of Aim for Social Change and a Managing Director at the Draper Richards Kaplan Foundation.

Stef van Dongen has over 18 years of experience in the impact sector. In 2018 he founded Pioneers of Our Time, a social enterprise that works for and with organisations and individuals to design impact strategies, build strategic partnerships, investment and philanthropic vehicles.

This was originally posted on the PSJP blog on December 18th 2020.

Want to keep up-to-date with more articles like this? Sign up to our newsletter.

Posted on 30 Dec 2020 Categories: Blog, Cross-posts, New economic models, The state we want