The Green New Deal: can we afford NOT to pay for it?

Posted on 06 Nov 2019 Categories: Blog, Climate crisis, Climate justice, The society we want, The state we want, Event reports

by Caroline Hartnell

On the 4 November, economist Ann Pettifor was speaking at the London School of Economics. ‘The Case for the Green New Deal’ was the title of her fascinating talk, and it is also the title of her new book.

Just the next day, 11,000 scientists endorsed a ‘World Scientists’ Warning of a Climate Emergency’, published in the journal Bioscience. The ‘warning’ pulls no punches:

‘We declare … clearly and unequivocally that planet Earth is facing a climate emergency … An immense increase of scale in endeavors to conserve our biosphere is needed to avoid untold suffering due to the climate crisis … To secure a sustainable future, we must change how we live. [This] entails major transformations in the ways our global society functions and interacts with natural ecosystems.’

The Green New Deal started in 2008, the brainchild of Pettifor and a group of English economists and thinkers. Unfortunately it was ignored within the tumult of the financial crash. A decade later, the idea was revived in the US, led by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. It was relaunched in the UK on 1 April 2019, as reported on by Rethinking Poverty. It is now official policy of the Green Party, while the Labour Party terms their version the Green Industrial Revolution.

The Green New Deal demands a radical and urgent reversal of the current state of the global economy, including total decarbonisation and a commitment to fairness and social justice. Critics have dismissed it as a pipe dream that could never be implemented, mainly because it would cost too much. We can afford it, Pettifor argued, but first we need to transform the global financial system. ‘Transformation needs to start tomorrow,’ she said. ‘We need cathedral thinking, big and structural, to save the planet and transform the economy.’

Transformation of the global financial system

Our present financial system is internationalised, with finance in control. According to US economist Alan Greenspan, the world is governed by global market forces, not by nations or politicians. The Green New Deal requires public authority over the ‘giant global spigot’ spewing out billions of dollars of credit, which fuels consumption, production and greenhouse gas emissions. ‘Money is the oxygen on which the fire of global warming burns,’ says Bill McKibben, environmentalist and co-founder of 350.org.

Tackling climate change demands disruption and redirection of the global financial system. To give an example, at present returns on investment in renewables are 5-8 per cent, compared to 15 per cent and over for fossil fuels. ‘We need structural change to drive investment to renewables.’

The ‘roaring lion’ that is the state has to front-end investments in energy, transport, land use, etc, said Pettifor, to enable the ‘timid mouse’ that is the private sector to invest and individuals to play their part. Only the state can do this because it can take risks.

Origins of the Green New Deal

To illustrate the relationship between the global financial system and nation states, Pettifor took us back to Keynes’s 1919 ‘Scheme for the Rehabilitation of European Credit and for Financing Relief and Reconstruction’, on which both the New Deal and the Green New Deal are based. The First World War brought collapse of international institutions and dissolution of the international system. Keynes saw that separation of the global financial system and representative democracy brings disaster. He was concerned to reintegrate markets with financial institutions, with public authority over the system. He recommended issuance of £1 billion in German government bonds, to be guaranteed by former enemy nations, to enable Germany to rebuild. Tellingly, the idea was rejected by Thomas Lamont, CEO of J P Morgan, on behalf of the US president. In his view it was private sources that had to finance reconstruction.

Keynes’ Grand Scheme was revived in Roosevelt’s New Deal in 1931 in response to the Great Depression. Unemployment was 25 per cent at the time. He dismantled the gold standard and demanded that banks and private citizens should hand over gold. The New Deal began with transformation of the international economic order, placing government rather than Wall Street in the driving seat. Roosevelt wanted to invest in jobs, social security, etc. Unskilled labourers were put to work planting 3 billion trees to transform the Dust Bowl and restore American agriculture. A fascinating detail: John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath was funded by a grant from the Roosevelt government.

What does the Green New Deal involve?

The Green New Deal requires that governments manage ‘the spigot that drives the global international juggernaut’, said Pettifor, creating public authority and management of the financial system. Under this scenario, central banks could exclude ‘brown’ assets from eligibility for central bank resources, which would go only to green assets. It could manage interest rates across the whole spectrum of lending and borrowing, and take control of international capital mobility. Governments could use tax breaks to incentivise the pension funds controlling trillions of dollars of individual savings to invest in the right things. An investment company like Blackrock, which has $6.5 trillion in assets, finds it easy to ignore the demands of national states, but they will see self-interest in having a stable global economy – which we certainly haven’t got now. ‘The question isn’t whether we will have another global financial crisis, but when,’ said Pettifor. Significantly, transformation needs to happen internationally, not just in one country.

The Green New Deal assumes:

- A ‘steady state economy’, abandoning the idea of perpetual growth and infinite expansion of the economy.

- Two budgets: the nation’s economic budget nested within its carbon budget. The mayor of Manchester is beginning to think about how to transform transport and services to stay within the city’s carbon budget (though he’s not going deep enough, said Pettifor).

- A largely self-sufficient economy, labour intensive, with a mixed market. ‘We have to grow our own green beans!’ rather than flying them in from Kenya. In a labour-intensive economy work will be revalued, so growing beans and caring for people with dementia will be valued activities. ‘Now running finance institutions is valued.’

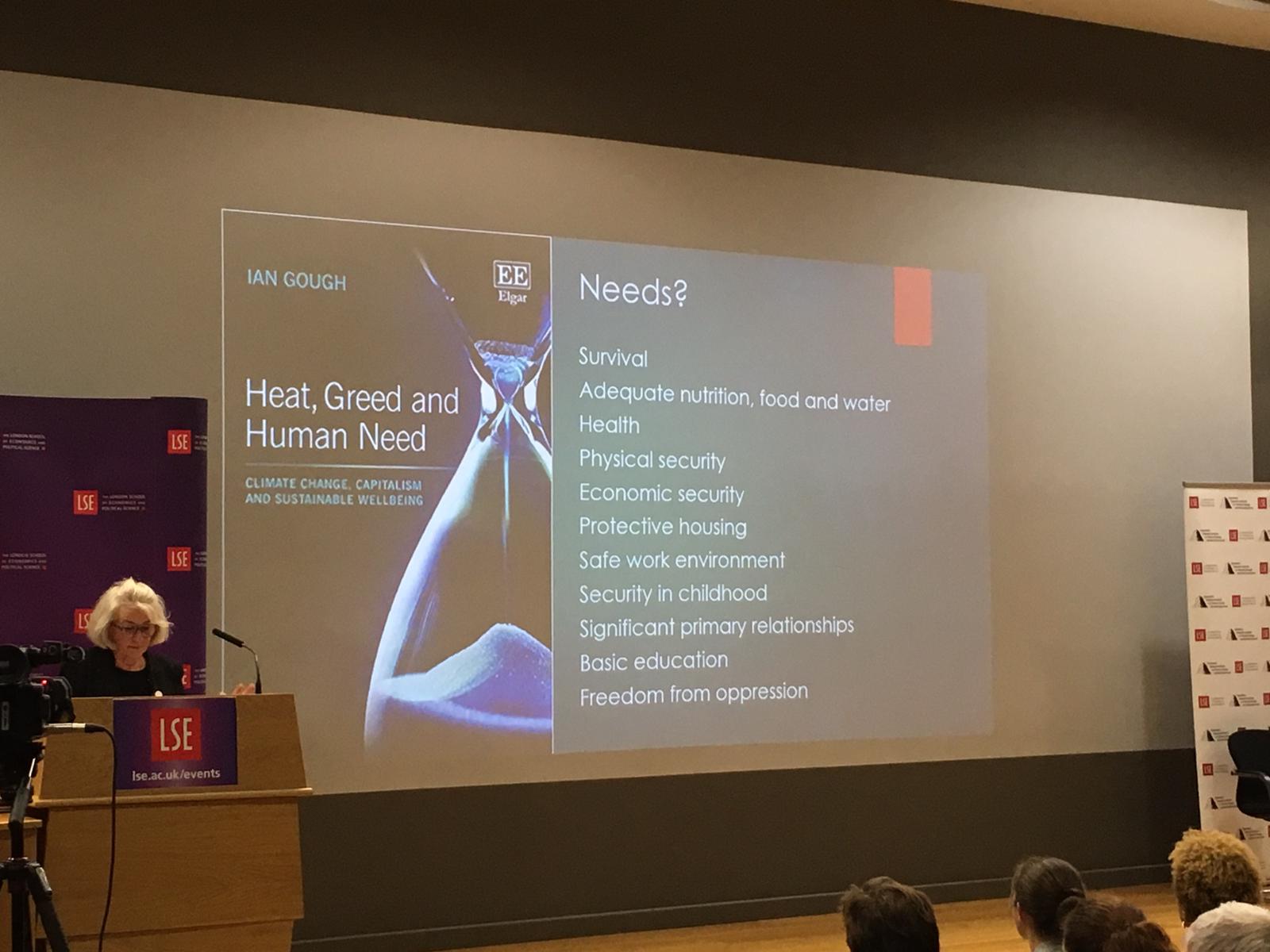

- Investment in limited needs not limitless wants.

Can we afford to pay for the Green New Deal?

The Green New Deal will cost a huge, as yet unknown, amount, said Pettifor, but we can afford it, she insisted. She proceeded to give us a lightning tour of the global financial system. While central banks provide credit at the macro level, ie to other banks and finance institutions, private banks provide credit to businesses and individuals. Then there is the ‘shadow banking’ system, defined by Investopedia as ‘the group of financial intermediaries facilitating the creation of credit across the global financial system but whose members are not subject to regulatory oversight’.

Adding all of this together, we have total global financial assets worth $377.8 trillion. So there’s no shortage of finance for the Green New Deal. The real questions are: who manages it? And where does it go? Speaking to an Extinction Rebellion audience in Trafalgar Square during their October Rebellion, Pettifor said she was against the idea of financing transformation through increasing taxes on everything. ‘I’m against that,’ she said, ‘because we built ourselves a monetary system for the very purpose of creating the finance we need to do what we can do. Keynes said something very profound: “we can afford what we can do.”’

Who will come up with the ideas?

In Pettifor’s view, the real shortage is of projects and plans for transformation of the global economy. Who will come up with the ideas? This was one of many questions from the audience. Projects need to be huge, said Pettifor, for example moving away from cars to more sustainable forms of transport. Here the state needs to have the big plan, and introduce the right incentives, and then the private sector will follow.

What we will need is movements to press from below for international leadership, Pettifor said. But where will they come from, it was asked. We are seeing political insurgencies around the world, but they are mostly moving in authoritarian directions. Progressive leaders will come from progressive movements, she said, like Greta Thunberg’s school climate strikers and Extinction Rebellion.

Can we do it in time?

If we were going to war, we would transform the system overnight. A catastrophic event may be needed – Cape Town running out of water, California on fire. In the UK St Albans is running out of water. ‘Governments will have to get in gear,’ she said, but what will be the trigger? Again, climate movements will need to keep up the pressure, always emphasising the very limited window of time we have to take action before it is too late.

Can national governments take meaningful action if the global system needs to be transformed?

Roosevelt was able to drop out of the global standard unilaterally because of the huge size of the US economy; he also exercised global leadership, resulting in the Bretton Woods agreement, negotiated in 1944 to establish a new international financial system. Following the 2008 financial crisis, measures were taken on an international scale, but unfortunately their aim was to save the banking system not to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and save our planet.

The EU provides a framework for countries to coordinate – which is why it’s such a disaster that we’re leaving Europe when we need cooperation to tackle global crises. In fact, said Pettifor, in response to another question, a European Green New Deal is feasible if countries cooperate. She is visiting three European countries in one week because of the level of interest in the Green New Deal. ‘We need leadership and movements from below.’ Pettifor returned to this theme as she rounded off her comments on Europe.

Given the urgency of the climate crisis, the question should perhaps have been ‘Can we afford not to pay for the Green New Deal?’ To which one can only give an unequivocal ‘No!’

Want to keep up-to-date with more articles like this? Sign up to our newsletter.

Posted on 06 Nov 2019 Categories: Blog, Climate crisis, Climate justice, The society we want, The state we want, Event reports