Pandemic truths 5: How Covid-19 shone a spotlight on the warped values of our current way of life

Posted on 23 Jul 2020 Categories: Blog, Climate crisis, Coronavirus

by Andrew Webster

‘What’s natural is the microbe. All the rest – health, integrity, purity (if you like) – is a product of the human will, of a vigilance that must never falter.’

― Albert Camus, The Plague

This is the fifth in a series of articles in which Andrew Webster reflects on ‘12 tough truths’ that have always been known, but which have been thrown into sharp relief by the pandemic. This article considers food production and air quality. Click here to read others in the series.

Truth 9: Industrial farming creates conditions conducive to new viruses that can transfer to human beings.

It is widely reported that the origin of the Covid-19 outbreak is a ‘wet market’ in Wuhan, China. There has been continuing controversy in the media about the hazards and cruelty of live animal markets in Asia and Africa. A closer look at the facts and risks shows that it is not a minority preference for freshly slaughtered meat that poses the risk; it is the majority’s growing consumption of mass-produced, refrigerated and processed meat.

The Covid-19 virus was first identified in a group of people in Guangdong, China in November 2019, and its genetic pattern shows it transferred at some point from animals. This is the closest scientists have come to identifying the origin of the virus. Coronaviruses are widespread in animals, and rarely transfer to humans. They are dangerous when they do. As the American physician, and advocate of plant-based nutrition, Michael Greger predicted in 2006:

‘There are three essential conditions necessary to produce a pandemic. First, a new virus must arise from an animal reservoir, such that humans have no natural immunity to it. Second, the virus must evolve to be capable of killing human beings efficiently. Third, the virus must succeed in jumping efficiently from one human to the next. For the virus, it’s one small step to man, but one giant leap to mankind. So far, conditions one and two have been met in spades. Three strikes and we’re out. If the virus triggers a human pandemic, it will not be peasant farmers in Vietnam dying after handling dead birds or raw poultry – it will be New Yorkers, Parisians, Londoners, and people in every city, township, and village in the world dying after shaking someone’s hand, touching a doorknob, or simply inhaling in the wrong place at the wrong time.’

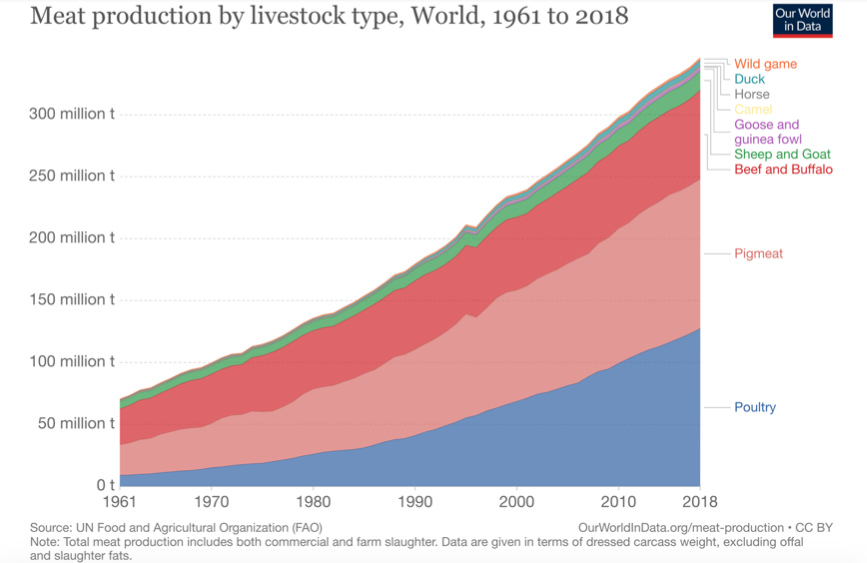

Research on the last 10 influenza epidemics shows that six of the viruses transferred from poultry and one from pigs. Hence the names ‘bird flu’ and ‘swine flu’. The sources were traced to China and the USA. Meat production has increased sixfold over the past 60 years. There are five times as many chickens reared for consumption as in 1960. Feedback, which researches the impact of meat production, estimates that by 2030 livestock will account for almost 50 per cent of CO2 emissions.

High-intensity livestock rearing creates the ideal conditions for virus spread and mutation. Thousands of genetically similar animals are kept close together, often indoors. Unvaried diets, lack of exercise and lack of sunlight suppress immunity, and antibiotics are widely used to tackle chronic infections. The animals are slaughtered in such numbers that they must be processed, refrigerated and then transported long distances before being bought and cooked. In comparison an animal kept in a yard, fed scraps, taken to a wet market, and slaughtered just before being cooked is positively healthy.

The meat production supply chain has increased the risks of contracting Covid-19. Many of the hotspots of infection in Germany and the UK have been in slaughterhouses or meat-packing plants. The Food and Environment Reporting Network (FERN) has mapped outbreaks in the meat supply chain in the USA and found that 40,099 workers had been infected at 401 sites resulting in 138 deaths.

The choices about healthy food are particularly stark in the UK today. Current EU animal welfare and food hygiene standards preclude the most efficient forms of industrial production. Meat produced in the USA is significantly cheaper than in the UK because regulatory standards are lower. Leaving the EU and allowing produce from less regulated markets will bring greater hazards for workers and consumers in the UK and increase demand for unsustainable methods of rearing livestock.

The businesses that own industrial meat plants are not local farmers; they are large corporations backed by investment and loans from international banks and pension funds. In contrast 50 per cent of the European fruit and vegetable supply comes from small farms, operating in local sustainable markets, and the EU mostly imports only specific fruits and vegetables that cannot be grown locally. Crop yields per hectare have trebled in the last 60 years, so continuing this trend and focusing resources away from meat production offers the real prospect of safer, healthier local food. The costs of not doing so are too high – for everyone’s health through pandemics, and for all our futures through climate change. The pandemic has shown we can’t afford cheap meat.

Truth 10: Air pollution kills people every day and is mainly caused by unnecessary oil-powered travel.

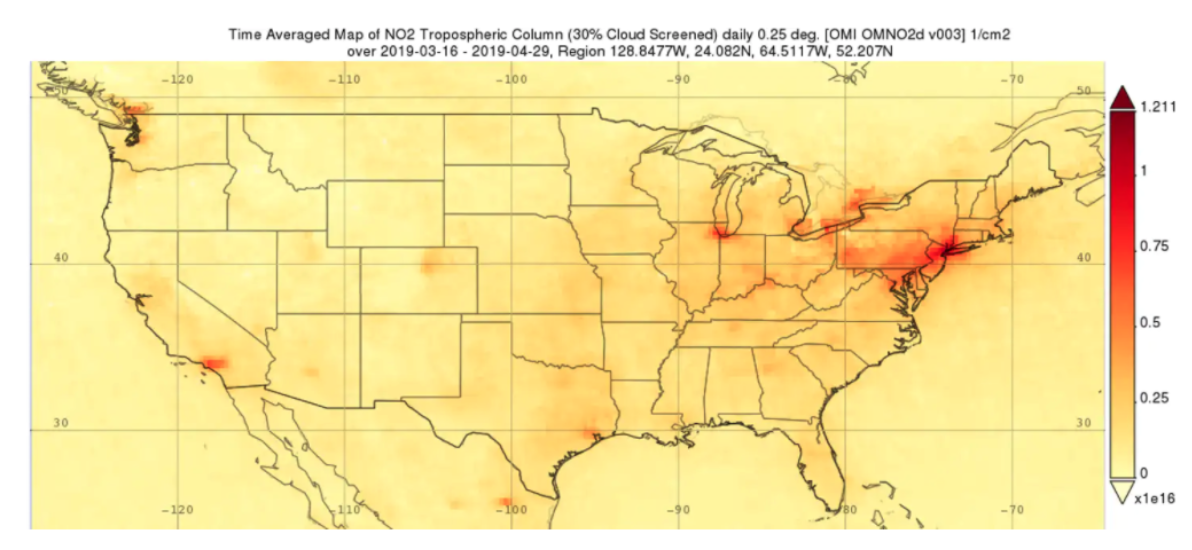

The World Health Organisation (WHO) calculates that 4.2 million people die every year as a result of air pollution. The principal pollutants are particulates, nitrous oxide, sulphur dioxide and ozone. The main sources of pollutants are cars, aeroplanes, and fossil fuels used for energy and cooking and some industrial processes. Observations of the USA from NASA showed clear reductions in pollutants during the lockdown.

The Covid-19 virus further highlighted the dangers of air pollution. Evidence began to emerge that those areas with the highest concentrations of air pollutants also had higher rates of infection and significantly higher death rates. This was first identified in northern Italy and Spain, where the areas of Lombardy and Madrid that regularly experienced high nitrous oxide levels experienced the worst outbreaks. This picture has since been repeated in major cities across the world.

What are the potential explanations for this? The first is a clear association between living in poor air and being on a low income, living in an overcrowded household, being black or minority ethnic, and being old. The same groups also have higher rates of the underlying conditions caused by poor air – asthma, COPD and heart disease – rendering them more vulnerable to infection and less able to recover from pneumonia induced by Covid-19. The second is the possibility that poor air helps airborne spread of the virus by providing microscopic hosts for it to pass between people. The third is that all these factors combine into a particularly toxic mix. It is still early days in the research but the associations are startling and disturbing.

Soon after lockdowns in major cities it became obvious that air quality had dramatically improved. Haze over New York, Los Angeles and other US cities notably diminished. The concentrations of nitrous oxide and particulates fell sharply in notoriously polluted cities in China. In Delhi the network of hazard warning screens that normally show pollution levels dangerous to life fell to acceptable levels. The Gate of India was clearly visible for the first time in decades. People locked down across northern India could see the Himalayas on the horizon. The virus had a silver lining.

The first image shows March/April 2019:

While this second one shows the same period in 2020:

Both images from Daniel Cohan, via NASA Giovanni, CC BY-ND

Subsequent monitoring by the WHO of cities across the world has shown that despite traffic levels increasing following the easing of lockdowns, pollution has not returned to pre Covid-19 levels. In London it is estimated that even where traffic levels are now 80 per cent of pre Covid-19 volumes, pollution remains very much lower. The explanation for this appears to be that congestion causes very much higher levels of particulate and nitrous oxide emissions because vehicles are stationary or stopping and starting frequently.

What should we take from this? Many governments, including Britain’s, were planning to phase out polluting vehicles by 2030, replacing them with electric vehicles, and to offset carbon emissions. This now looks a timid response, given that the pandemic has shown that many journeys are unnecessary or avoidable and that there is an appetite to shift to walking and cycling. Demand for air travel has fallen and will likely not recover. In Britain cycle sales have increased 60 per cent during the lockdown. Responding to these changes demands a wholesale redesign of cities to reduce commuting and to create local workspaces, local supply systems and non-polluting transport networks. The Mayor of Paris has already won re-election on a pledge to create a 15-minute-accessible city centre. Green politicians were elected on similar platforms in other large cities in France in June 2020. Sustainable, healthy cities are within reach and can save millions of lives.

In the final article I will look at tough truths about rights, responsibilities and leadership.

Andrew Webster is a Trustee of Centris and an advisor to health and care systems and businesses, having worked in the NHS, Local Government and Central Government for 35 years.

Want to keep up-to-date with our coronavirus coverage? Sign up to our newsletter.

Posted on 23 Jul 2020 Categories: Blog, Climate crisis, Coronavirus