Pandemic truths 4: How Covid-19 shone a spotlight on the warped values of our current way of life

Posted on 07 Jul 2020 Categories: Blog, Coronavirus

by Andrew Webster

‘All I maintain is that on this earth there are pestilences and there are victims, and it’s up to us, so far as possible, not to join forces with the pestilences.’

― Albert Camus, The Plague

This is the fourth in a series of articles in which Andrew Webster reflects on ‘12 tough truths’ that have always been known, but which have been thrown into sharp relief by the pandemic. This article considers racism and violence against women. Click here to read others in the series.

Truth 7: If you are poor and black you will live in poorer circumstances and suffer poorer outcomes.

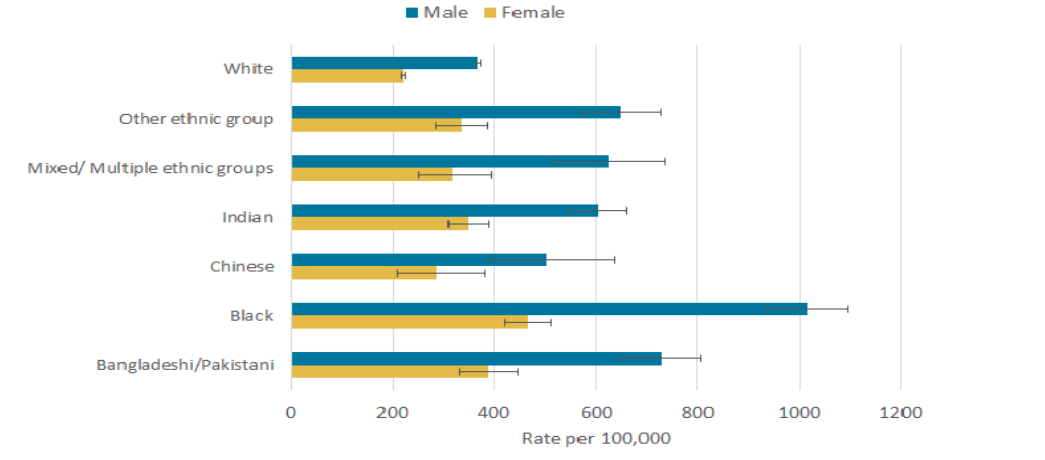

Even before the recent Black Lives Matter demonstrations brought the issue to our streets, it was painfully evident that COVID-19 had affected BAME people much more severely than white people. The Office of National Statistics found that working age black men were four times more likely to die of the virus than their white peers, while older black women were over twice as likely to die. Once admitted to hospital, Asian people were three times more likely to die than white people. It is very early to do a detailed analysis, but socio-economic factors account for half the difference. So, simply as a result of poorer life chances, reinforced by white privilege, thousands of BAME people have suffered and died from the illness. Equally, there appears to be no genetic reason why people of different races should be differently affected – scarcely surprising given that the genetic differences between races are less than those within them.

Age-standardised rates for deaths involving COVID-19 at ages 9 to 64 years by sex and ethnic group, per 100,000 people: England and Wales, occurring 2 March to 15 May 2020

Age-standardised mortality rates for deaths involving COVID-19 at ages 65 years and over by sex and ethnic group, per 100,000 people, England and Wales, deaths occurring 2 March to 15 May 2020

Some have advanced the explanation that people from BAME groups are at greater risk – they are over-represented in occupations that are exposed to infected people, for example care workers, retailing, health staff, bus drivers. It is certainly true that nearly two thirds of the health workers who have died of COVID-19 were from BAME backgrounds, some working in high-risk specialities like ENT surgery, but others in much lower-risk roles. The truth is that BAME people are over-represented in many causes of early death and disability. The Mental Health Foundation reported in 2019 that in the UK, Afro Caribbean people were nearly seven times more likely than white people to be diagnosed with a psychotic illness, while Asian people were about as likely to be diagnosed as white people and Chinese people less likely. They identified four drivers: racism and discrimination; social and economic inequalities; stigma and the criminal justice system.

We have already seen that social and economic inequalities caused excess mortality. COVID-19 did spread in prisons, and as ever young black men were disproportionately checked for obeying the lockdown, but the criminal justice system did not drive COVID-19 outcomes. Racism, discrimination and stigma were the strongest factors.

The racist foundations of our current social order sparked the toppling of Edward Colston in Bristol and widespread public demonstrations of solidarity following the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis. But they also underlie the injustice of unnecessary illness and death for many BAME people in the pandemic. Of course, progress towards equality has been made in the 200 years since the abolition of slavery, but our economy, laws, education and health systems only compensate for fundamental flaws in our still colonial and racist culture. Yes, we need reform of our institutions, and to stop commemorating slaver philanthropists, but more fundamentally we need a national dialogue about the dark and complex truth of African enslavement and its contribution to European and American dominance.

Truth 8: Every day violent men terrorise women and children and force them to flee their homes into public care.

For many of us home has been a safe place during lockdown, protected from risk of infection and surrounded by support from our family, neighbours and community. Even for vulnerable people it has been possible to make home a bit safer with regular contact, food deliveries, support with health care and access to volunteers. Imagine then the polar opposite. Lockdown means being in the same house as a person, nearly always a man, who controls you, frightens you and your children, threatens you with violence and shame, abuses you and your loved ones, regularly harms you physically and mentally. And, in a world where there is no escape or respite, no time at work, collecting kids from school, going out to visit family, friends and others offering support, no private access to social media. Information about how to flee and where to flee to is harder to find, even harder to act upon. The possibility of infection means that you cannot keep your whereabouts as secret as you’d wish.

Standing Together has collected information from domestic violence support and survivors’ organisations across England and found that demand for refuges has significantly increased in the 12 weeks of lockdown, while the places available have been reduced by quarantine and protective measures. Overall places available in April 2020 were half the level of that in 2019 and that was already too few in many parts of the country. Reported violence increased by 8 per cent and Counting Dead Women report that 26 women have been killed by their partners since the start of the lockdown. These findings are similar to those reported by the police.

Standing Together has collected information from domestic violence support and survivors’ organisations across England and found that demand for refuges has significantly increased in the 12 weeks of lockdown, while the places available have been reduced by quarantine and protective measures. Overall places available in April 2020 were half the level of that in 2019 and that was already too few in many parts of the country. Reported violence increased by 8 per cent and Counting Dead Women report that 26 women have been killed by their partners since the start of the lockdown. These findings are similar to those reported by the police.

Supporting women at risk from domestic violence has also been much harder during the pandemic. Effective support is best delivered by organisations led by and for specific communities. We have seen above how BAME communities have been disproportionately hit by the virus, and so too have black-led support and survivors’ groups. Women who are refugees or recent migrants are at particular risk. Their exclusion from public funding was already a hazard, now exacerbated by fears that protecting their health and safety will lead to confinement or deportation.

The government had previously made tackling domestic violence a priority, reflecting the concerns of the former PM Theresa May. It has also allocated an additional £37 million to organisations to help them during the lockdown and pandemic. In common with other additional grants, there has been widespread confusion about how exactly these funds will be distributed. Both existing policy and the additional response are founded on assumptions that do not survive contact with a pandemic – ie that women and children should be helped to flee violent men by leaving their homes and seeking refuge in a safe and secret place. The courts should then ensure that restraints are placed on the perpetrator. This approach places disproportionate risk, personal, emotional and financial, on the person suffering abuse (and her children). Refuge is hard to find, fleeing is complex and hazardous, work, education and social support are further disrupted by changing home, and the courts are too slow to adequately restrain perpetrators.

As Standing Together say in their open letter to the Prime Minister, the discourse needs to change from ‘why doesn’t she flee to why doesn’t he stop?’ When a home is unsafe, surely the first response should be to remove the source of danger. But the police, housing management and social services have no power to do that without court sanction. Of course, the rights of alleged perpetrators must be defended properly, but a principle of do less harm must support a policy of temporary removal of alleged perpetrators. The pandemic has illuminated a fundamental imbalance.

In the next articles I will look at the tough truths about food, space and mobility, and finally at rights, responsibilities and leadership.

Andrew Webster is a Trustee of Centris and an advisor to health and care systems and businesses, having worked in the NHS, Local Government and Central Government for 35 years.

Want to keep up-to-date with our coronavirus coverage? Sign up to our newsletter.

Posted on 07 Jul 2020 Categories: Blog, Coronavirus

Hi Andrew

I have been greatly enjoying your articles.

I do wonder why you did not perhaps mention the following in Truth 7:

“South Asian people are at highest risk of dying from Covid-19 after being admitted to UK hospitals, even when factors such as obesity are taken into account, the biggest study of its kind has found. Data from 30,693 people admitted to 260 hospitals found a 19% increased risk of death with coronavirus for those who were South Asian compared with white people. Experts behind the study said 40% of the South Asians in the group had diabetes – which was a “significant factor” in their increased risk of death.”

Not proven yet but diabetes does appear to be a significant factor alongside age, obesity, COBD etc, etc.

Best regards

Mark