Climate justice and social justice must go together

Posted on 18 Jun 2019 Categories: Blog, Climate crisis, Climate justice

by Stephen Pittam

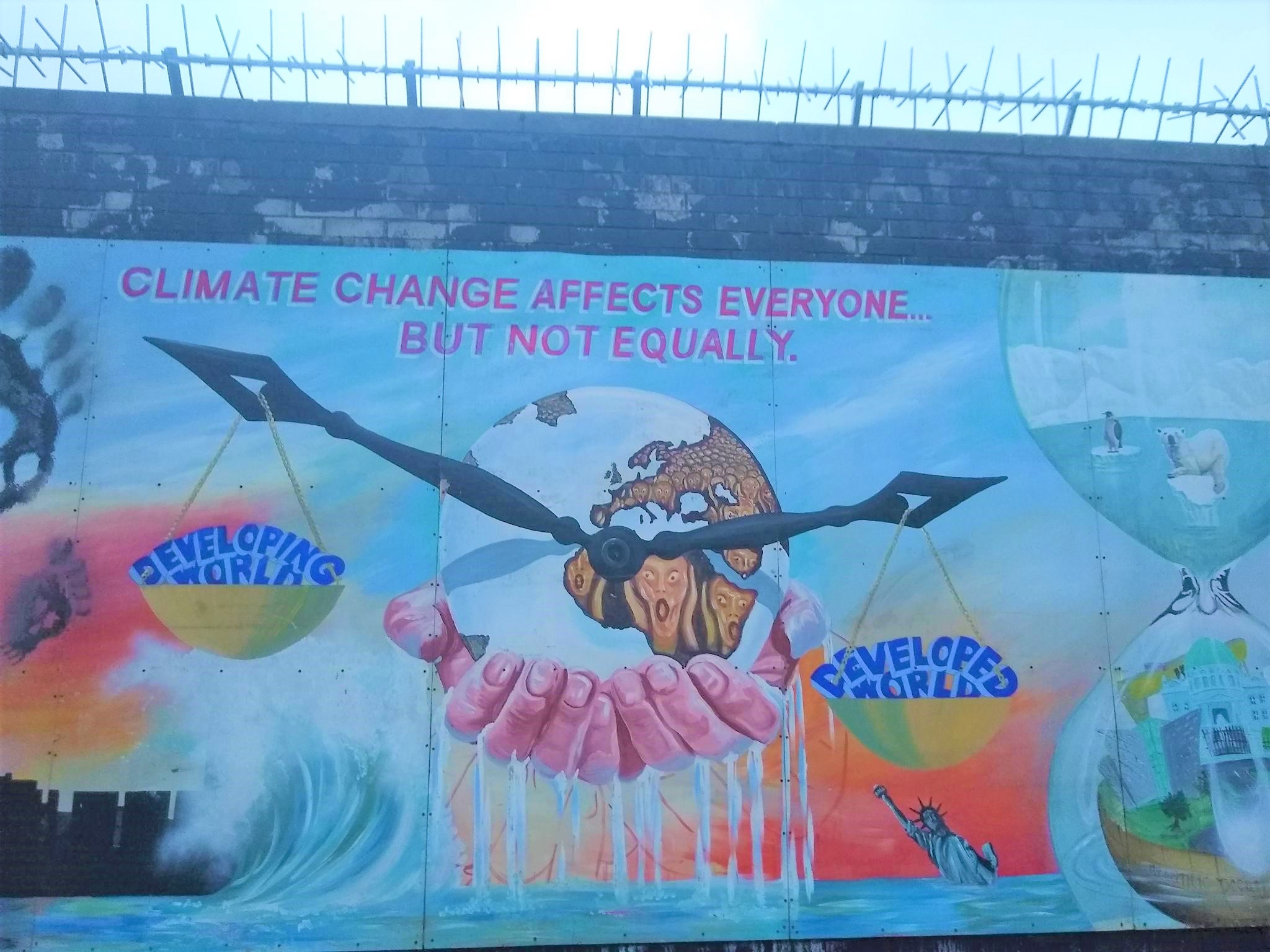

In April I attended Ariadne’s annual meeting in Belfast. Ariadne is a European peer-to-peer network of over 600 funders and philanthropists who support social change and human rights. Participants enjoyed the special hospitality that Belfast always offers its visiting guests, including a tour of the peacelines and murals. And what could serve better to frame the final plenary for this event, which focused on Human Rights in a Changing Climate, than the climate change mural on the International Wall on the Falls Road in West Belfast. It sums up perfectly the reason why the climate justice movement and the social justice movement are so intricately intertwined. The world’s poorest are the most vulnerable to extreme weather and other climate events and have the least resources to cope with the impact. The image of who will suffer most as a result of climate change could equally apply to the domestic agenda in the UK.

The Joseph Rowntree Foundation has been in the forefront of work on climate change and social justice in the UK. Its 2014 overview of the field reviewed more than 70 studies and was a really useful document. It would be great if five years later it could be updated, but sadly the programme has ended.

Climate change affects the poorest in the UK most

Take transport for instance. The review highlighted the inequitable distribution of carbon emissions. The wealthiest 10 per cent of households in the UK were responsible for 10 times more carbon emissions from international aviation than the lowest, and 7-8 times more from personal transport. And yet little consideration has been given to how responsibility for emissions might inform responsibility for mitigation responses. The government’s overall domestic sustainable energy policies were forecast to produce a situation by 2020 where the richest 10 per cent of households might see an average reduction of 12 per cent in their energy bills while the poorest 10 per cent are expected to see a reduction of only 7 per cent.

The review describes multiple ways in which lower income and vulnerable groups are disproportionately affected by climate change and associated policies to address the crisis. But it also goes on to indicate that it is possible to achieve carbon reduction targets in a socially just way and that concrete examples of adaptation and mitigation practice are beginning to emerge at the local level, which also address social justice questions. This mirrors the experience of the Global Greengrants Fund, one of the sponsors of the final plenary at the Ariadne event, whose work has shown that local communities whose lives are most affected often come up with the best solutions to environmental harm and social injustice. The two themes are closely interconnected.

How can the UK meet its emissions targets?

Spurred on by the amazing activists of Extinction Rebellion, the school students’ strikes, and the initiatives of dozens of towns and cities across the UK, the UK government has now declared a climate emergency. In an attempt to create a positive legacy, Theresa May has recently pledged to introduce a legally binding target forcing the UK to meet net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. Many will argue that this is too little too late, but the gulf between the rhetoric and reality feels huge at the moment given that the government is not even on track to meet its current significantly more modest targets.

It doesn’t have to be this way. It will take a radical change in policy and practice to get there, but it is possible to envision a different world. The last meeting of the UK-based Environmental Funders Network focused on the changes needed. Ed Miliband, Caroline Lucas and Laura Sandys introduced the new IPPR Environmental Justice Commission (of which they are the co-chairs) which aims to infuse the debate on climate change with hope and to confront the climate crisis with policies that promote social and economic justice.

Climate justice: enter the Green New Deal

This initiative talks about the green transition, and has in many ways been inspired by the thinking which emerged in 2008 through the Green New Deal Group of which Caroline Lucas is a member. The Group’s 2008 report was, in my opinion, the best piece of analysis that came out of the financial crisis of that time. It proposed a labour-intensive green infrastructure programme which would tackle the crisis of climate change and help mitigate the effects of the huge economic downturn which the Group correctly predicted. It talked about rebuilding a sense of hope and creating economic security for all, while fully protecting the environment.

Sadly, once the immediate threat of economic collapse had receded, the country moved to the right and new Keynesian ideas were replaced with monetarist policies. We moved into the era of austerity – a policy of choice rather than necessity, which has led to further damage to the environment and fuelled the further rise of inequality and poverty.

Now, support for the Green New Deal is growing once more as the scale of the climate crisis has broken through into public consciousness. The idea, developed in the UK, has been exported to the USA where the name resonates so closely with Roosevelt’s original New Deal. There, it is championed by the charismatic, youngest-ever member of the House of Representatives, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. The increased profile has resulted in the idea being imported back to the UK, where it was formally launched at the House of Commons on 1 April, into an environment that is far more worrying than in 2008 but potentially more favourable to receiving it.

Colin Hines, the primary author of the 2008 Green New Deal pamphlet, has described what a Social and Green New Deal would involve. It would mean rejecting austerity and instead massively increasing employment in face-to-face caring and a countrywide green infrastructure programme. The latter would involve making the UK’s 30 million buildings super-energy-efficient, and tackling the housing crisis by building affordable, properly insulated new homes. Local public transport would be rebuilt, the road and rail systems properly maintained, and a major shift to electric vehicles instigated. A more sustainable localised food and agricultural system would be developed. This approach is labour-intensive, takes place in every locality, and consists of work that is difficult to automate.

How would it be paid for? By an increase in government spending, fairer taxes and encouraging saving in what Hines has described as ‘climate war bonds’. And in the event of a further looming economic crisis? A massive Green Quantitative Easing (GQE) programme. After the last crash US$10 trillion was injected into the global economy, but not into job-generating investments. The result was inflated stock and property values for the already well off. The Governor of the Bank of England has hinted that some kind of GQE programme might be possible as a way of addressing climate change.

Integrating social justice in climate change policy

The JRF report concluded that it is not just a moral imperative to integrate social justice in climate change policy. Without this, achieving resilience and mitigation targets will be much harder because the transformation of our society that is needed cannot be achieved without the political and social acceptance that results from fairer policies. Furthermore, developing socially just responses to climate change, in terms of both adaptation and mitigation, is an opportunity to put in place governance, systems and infrastructure that will create a more resilient and fairer society. As Caroline Lucas concludes in a Guardian opinion piece published on 27 March, we need:

‘an unprecedented mobilisation of resources invested to prevent climate breakdown, reverse inequality, and heal our communities. It demands major structural changes in our approach to the ecosystem, coupled with a radical transformation of the finance sector and the economy, to deliver both social justice and a liveable planet.’

Rethinking poverty cannot be separated from the biggest issue of our time – addressing climate change. Successfully addressing climate change, though, will inevitably lead to a fairer, more equal society.

Stephen Pittam is a board member of Global Greengrants Fund and chair of Global Greengrants UK.

Want to keep up-to-date with more articles like this? Sign up to our newsletter.

Posted on 18 Jun 2019 Categories: Blog, Climate crisis, Climate justice